Current status of anterior ankle impingement

Estado actual del pinzamiento anterior de tobillo

Resumen:

El pinzamiento anterior de tobillo (PAT) ha pasado de considerarse una entidad aislada, típicamente ósea, a integrarse en un síndrome complejo frecuentemente vinculado a inestabilidad crónica del tobillo. La evidencia reciente indica que muchos casos de PAT –sobre todo los anterolaterales de partes blandas– se originan en inestabilidades crónicas del tobillo, incluidas microinestabilidades. La artroscopia ha revolucionado el diagnóstico y el tratamiento al permitir una evaluación minuciosa de las estructuras intraarticulares y facilitar la resección de osteofitos o tejido hipertrófico, además de la reparación ligamentosa cuando procede. Este enfoque integral disminuye la recurrencia de los síntomas y mejora los resultados. La identificación precisa de los factores biomecánicos asociados y el planteamiento de nuevos estudios son claves para optimizar el manejo clínico del PAT.

Nivel de evidencia: V.

Abstract:

Anterior ankle impingement (AAI) has evolved from being considered an isolated, typically bony condition to become part of a complex syndrome often linked to chronic ankle instability. Recent evidence indicates that many cases of AAI, especially anterolateral soft tissue AAI, originate from chronic ankle instabilities, including micro-instabilities. Arthroscopy has revolutionized diagnosis and treatment by affording a thorough assessment of intra-articular structures and facilitating the resection of osteophytes or hypertrophic tissue, as well as allowing ligament repair where indicated. This holistic approach reduces the recurrence of symptoms and improves the outcomes. Accurate identification of the associated biomechanical factors and the conduction of new studies are key to optimizing the clinical management of AAI.

Level of evidence: V.

Introduction

The concept of anterior ankle impingement (AAI) has undergone significant changes in recent decades. In the last decade, ankle arthroscopy has developed considerably and is establishing itself as a standard in the diagnosis and treatment of different foot and ankle disorders(1,2). Until a few years ago, ankle arthroscopy was mainly indicated for talar osteochondral injuries or anterior impingements, usually as sequelae to sprains; however, its indications have now been greatly expanded(3). In the case of AAI, many studies have reported good results after simple resection of the interposed soft tissue or osteophytes, though with the recurrence of symptoms after some time(4). There is now ample scientific evidence to support the association between many of these impingements and ankle instability, which implies the need to combine resection with ligament repair or reconstruction techniques(3,5,6,7).

The question that arises is whether the concept of AAI, specifically referred to those cases caused by soft tissue, is still relevant today or whether these are simply associated lesions secondary to an underlying disorder related to chronic instability. The present article analyzes the current status of AAI and its relationship to chronic ankle instability, and discusses whether it can still be considered an isolated disease condition.

Definition

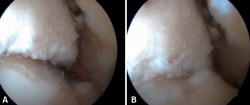

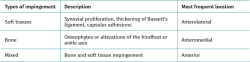

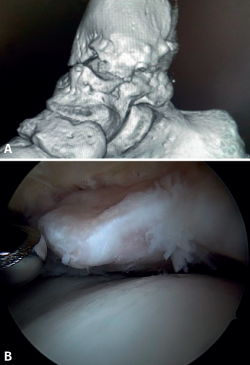

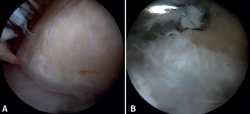

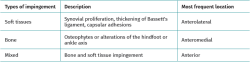

Anterior ankle impingement is defined as pain and/or limitation of range of motion that occurs with dorsiflexion of the ankle, due to the presence of soft tissue or bone interposed between the joint surfaces. A distinction is made between soft tissue impingement (synovial proliferation, thickening of Bassett's ligament, capsular adhesions), bony impingement (osteophytes or alterations in the ankle or hindfoot axis) (Figure 1) and mixed impingement (Table 1). AAI in turn can be subdivided into central, anterolateral and anteromedial impingement(8), with the first two being the most common presentations(9). Anterolateral AAI usually involves soft tissue, while anteromedial AAI is usually caused by a spatial conflict between osteophytes of the talar neck and anterior to the medial malleolus in dorsiflexion(9,10). AAI is the most common cause of anterior ankle pain that worsens with dorsiflexion. However, posterior impingement may be more frequent in certain patient groups, such as dancers or football players, due to repetitive movements in forced plantar flexion(4).

Morris first described AAI in 1943(11). Years later, McMurray coined the term "footballer's ankle" (12). In 1957, O'Donoghue referred to "impingement exostoses" (13). Wollin, in 1950, first described soft tissue impingement involving Bassett's ligament(14,15). In 1991, Ferkel and Scranton described the pathophysiology of anterolateral ankle impingement syndrome, indicating that an ankle sprain that injures the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) may result in incomplete healing of the latter(15). Repetitive movements can cause synovitis and fibrosis, forming a painful mass of soft tissue in the joint space. The pain should disappear weeks after complete healing of the ATFL.

Etiopathogenesis

Anterior ankle impingement was originally described as a bony impingement caused by exostoses or osteophytes, without considering etiologies other than primary osteoarthritis or repetitive trauma to the ankle. Subsequently, the concept of soft tissue AAI was introduced, based on observation of the proliferation of anterolateral scar tissue following an ankle sprain. AAI can be post-traumatic (ankle fractures, sprains), post-surgical (scar tissue) or due to sports microtrauma. In soft tissue impingement, meniscoid lesions, scar tissue hypertrophy and Bassett's ligament impingement have been described as the cause of pain(16). The presence of osteophytes or scar tissue is not necessary for AAI to occur; a displaced calcaneal fracture subjected to orthopedic treatment can cause horizontalization of the talus and anterior impingement(17). In the sequelae of distal tibial fractures or physeal growth disturbances, a recurvatum deformity may be the cause of pain, due to anterior impingement of the ankle(18). Osteoarthritis of the ankle is characterized by the presence of osteophytes in its early stages, which may lead to AAI(19). Chronic ankle instability and post-traumatic injuries following fracture are the most common causes of such osteoarthritis(20).

Kissing osteophytes, which refer to the simultaneous presence of osteophytes on the anterior border of the talus and tibia,have been considered a source of anterior ankle pain due to the mechanical impingement they cause upon impact with each other during movement(21). However, this theory has now been abandoned, as many authors have shown that there is no real contact between the two osteophytes during ankle dorsiflexion(22). The tibial osteophyte is more medial and the talar osteophyte is located more lateral. Other studies have shown that osteophytes are asymptomatic in 45% of football players and in 59% of dancers(23).

The association between AAI and chronic ankle instability is a more recent concept(5,24,25). Ferkel considered that the presence of anterolateral ankle impingement (ALAI), although related to inversion trauma, excludes the diagnosis of ankle instability(10). However, different studies reported recurrence of the symptoms after the isolated treatment of anterolateral impingement through simple resection of the osteophytes or interposed soft tissue, such as a persistent sensation of instability or new sprain episodes, as described by Katakura et al.(26) in a systematic review on ALAI and its relation to ankle instability. They identified 8 studies with level IV evidence, of which 5 mentioned the presence of recurrent instability or sprains. One study described the presence of concomitant ATFL lesions. The ankle sprain recurrence rate after simple impingement resection treatment ranged from 8-20%. The authors concluded that simple resection of hypertrophic tissue in ALAI has a limited level of scientific evidence, and suggested that all patients to be surgically treated for AAI should also be checked for ATFL status.

Vega et al. reported that the inferior fascicle of the ATFL is located extra-articular, while the superior fascicle is intra-articular, which may imply a reduced healing potential, as seen with the anterior cruciate ligament(27). Lack of adequate healing of the superior fascicle of the ATFL can lead to micro-instability(5,28,29), a concept previously described in the shoulder(30). In the past, many of these patients were diagnosed with functional instability, a concept coined by Freeman in 1965(31). Radiological stress tests have significant limitations in terms of sensitivity(32) and great variability in the range of physiological values and reproducibility(33,34). As a result, they are not considered necessary for the diagnosis of acute or chronic ankle instability(35), since they may underdiagnose more subtle instabilities. The concept of micro-instability has represented a paradigm shift in the assessment and management of these patients who previously would have been diagnosed and treated as cases of ALAI. This has led to a therapeutic approach focused on joint stabilization, leaving the treatment of impingement (whether of bony or soft tissue origin) as a matter of secondary relevance.

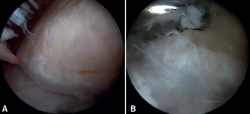

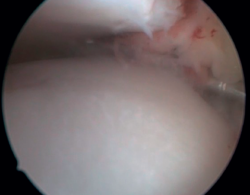

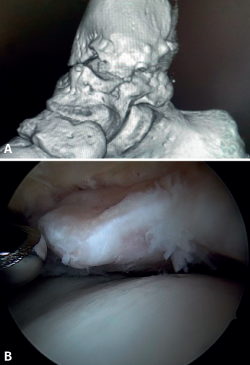

Bony AAI due to osteophytes has also been linked to the presence of chronic instability. It has been postulated that altered joint kinematics secondary to ligament insufficiency favors the development of osteophytes in the anterior region of the tibia and talus(36,37). Recent studies have questioned the theory of repeated capsular traction as the origin of osteophytes in sports(38), as it is easily demonstrated that osteophytes are located intra-articular within the capsular insertion, in the context of ankle arthroscopy (Figure 2). Therefore, ankle dorsiflexion arthroscopy is essential to safely resect osteophytes without damage to the capsule or overlying structures, whereas the classical traction technique (invasive or otherwise) would make resection extremely difficult, and is thus not recommended nowadays for routine use(3,39). Vega distinguished between two types of osteophytes(3), according to whether they are caused by repetitive trauma (peak-shaped) or instability (visor-shaped). The concept of micro-instability is associated with repetitive micro-trauma, which could be the origin of osteophytes with this characteristic morphology (Figure 3).

Another concept is that of rotational instability, in which the anterior part of the deltoid ligament suffers degenerative injury due to the micro-movements in anterior drawer and internal rotation caused by primary anterolateral instability. Up to 40% of all chronic instabilities are considered to be of this type(3). Medial and lateral pain may be the only clinical manifestation, in the same way as AAI.

Bassett's ligament has long been considered a pathological structure and a cause of anterolateral impingement, so resection of this ligament was included in the surgical protocol for the treatment of AAI(40). This ligament is the intra-articular portion of the anteroinferior tibiofibular ligament of the syndesmosis. In relation to its involvement in AAI, it seems to play more of a victim's role, since the micro-movements of the talus in the mortise produce micro-traumatisms that can thicken or damage the ligament. Nowadays, this ligament is considered to have proprioceptive capacity, due to contact with the talar dome at ankle dorsiflexion; it is therefore advised to avoid its resection(41).

Clinical manifestations

The pain generally appears during movement and subsides or disappears at rest, i.e., it has clear characteristics of mechanical pain. It is usually located on the anterior aspect of the tibioperoneal-talar mortise, either along its entire length or locally on the medial or lateral groove. The pain may be associated with the presence of edema and limitation of ankle dorsiflexion. In anterolateral ankle impingement, the persistence of any of these symptoms for more than 6 months after an ankle sprain is considered a clinical diagnostic criterion. These symptoms are often associated with recurrent sprains or subjective feelings of instability or kinesiophobia. The patient usually recalls having suffered a sprain, which makes us suspect a strong causal relationship between the presence of AAI and chronic ankle instability. Patients often report limitations associated with pain, stiffness, locking and/or clicking when climbing stairs or slopes and, in general, any activity requiring forced dorsiflexion of the ankle. Clinically, the signs and symptoms of AAI overlap with those of chronic ankle instability, which may be taken as a further confirmation of their close relationship.

Physical examination

The Molloy test(42)has been described for the exploratory diagnosis of AAI; it is performed by anterolateral painful palpation of the anterior region of the ankle, with increased pain being noted on dorsiflexion of the ankle. A sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 94.8% has been reported(42). The presence of pain on palpation at the talar insertion or on the anterior aspect of the external malleolus, or the presence of an anterior ankle drawer would suggest possible ankle instability associated with ATFL injury; in our experience, this happens often. Liu(43) considered pain with single-leg squat and pain with ankle dorsiflexion to be diagnostic criteria for ALAI.

Palpation should be used to locate the pain in the anterior mortise at the joint line and at the grooves. Pain in the anterior aspect of the external malleolus may be related to ATFL injury, and we should avoid confusion with neighbouring regions such as the sinus tarsi (which may indicate the presence of subtalar arthrosis, subtalar instability, valgus foot impingement, etc.), peroneal tip pain (due to peroneal subfibular impingement), pain in the syndesmosis due to instability at this level, lateral talar osteochondral lesions, etc.

AAI, especially bony AAI, may result in a loss of the last degrees of ankle dorsiflexion, which may be evidenced on examination. The Lunge test is performed by comparing the distance from the toe of the healthy foot to the wall, achieving contact of the patella with the same wall without lifting the heel off the ground, with the shorter distance of the ankle with limitation of dorsiflexion. The test is able to override the action of the calf, but not the presence of equinus due to other causes, such as a shortened soleus or shortening of the posterior capsule; it is of little use in differentiating these causes from bony anterior block. The same applies to hyperpronation of the foot, which can compensate for this dorsiflexion defect. Nevertheless, it is a useful test, provided that these differential diagnoses can be ruled out. The Silfverskiöld test also allows us to assess whether the loss of dorsiflexion is, in fact, a case of calf-dependent equinus.

In all patients it is important to detect the presence of infra- or supra-malleolar varus or valgus axial deviations that can lead to osteoarthritis with the consequent formation of osteophytes; to this end, it is essential to examine these patients in the standing position.

Imaging diagnosis

Ankle and foot weight-bearing radiography is used to detect alterations in mechanical alignment of the ankle. Osteophytes may be clearly visible on lateral ankle radiographs, although Van Dijk et al.(8) described a radiological projection to detect more lateral locations, involving a lateral projection with 30° of external rotation. This projection doubles the sensitivity and specificity of plain lateral radiography(44). Computed tomography (CT) is the definitive test to locate and visualise the osteophyte in three dimensions.

In case of suspected soft tissue AAI, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered the technique of choice, although some authors consider physical examination to be more sensitive(45). MRI arthrography increases the ability to detect AAI with a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 97%(46).

Arthroscopic diagnosis

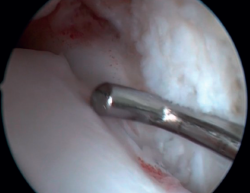

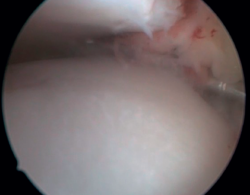

The confirmation of AAI is made by direct vision during arthroscopic examination (Figure 4). This technique allows us to visualise the entire joint, assess the state of the articular cartilage and ligaments, detect the presence of capsular adhesions, synovitis, synovial thickening, loose bodies, etc. It also allows us to carry out functional tests to reveal possible associated instabilities or to assess how the soft tissues causing pain suffer impingement. In our experience, the presence of ATFL lesions is very frequent.

Conservative management

Conservative management varies depending on the disorder associated with AAI. In cases of altered hindfoot alignment, corrective insoles may be useful. For the associated chronic instability, the patient may find relief of symptoms with the use of ankle braces or functional bandages. Heel cups or raised heel shoes can reduce impingement and the intensity of pain.

Intra-articular infiltrations of corticosteroids with local anesthetic, hyaluronic acid, platelet-rich plasma, etc. may have some effect in terms of temporary pain control(47).

Surgical treatment

Arthroscopy has become the gold standard in the treatment of AAI and its associated causes. This technique allows precise diagnosis and visualization of the type of impingement in a dynamic manner, by applying the pertinent maneuvers. Even in cases of large osteophyte formations, arthroscopy is feasible using the forced dorsiflexion technique, since the insertion of the joint capsule into the tibia is located a few millimeters dorsal to them. Traction is not necessary and may even be considered contraindicated in this disease condition, due to the risk of tendon or neurovascular injury.

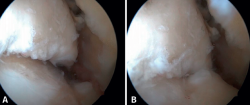

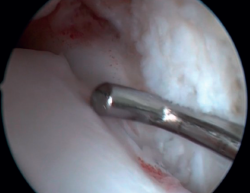

Resection of the osteophyte is performed by displacing from the top, and gradually reducing it until the joint zone is reached (Figure 2). A basket forceps can be used to resect the area closest to the joint (Figure 5). It is often useful to exchange the viewing and working portals in order to visualize and completely resect the osteophytes. In the case of soft tissue impingement, a 3.8 or 4 mm synoviotome is usually sufficient. The vaporizer is useful in the case of compact impingements, typical of post-traumatic conditions or re-interventions, and also for delimiting the bony part of the osteophyte before resection.

Bassett's ligament should be preserved as long as it does not have a pathological appearance, ruling out thickening, partial tears or reciprocal lesions on the anterolateral surface of the talus (Figure 6), which are associated with anterolateral or rotational instabilities. The peroneal insertion is used as a reference to locate the distal insertion of the ATFL. The deltoid ligament at the medial groove should be inspected if associated rotational instability is suspected. During arthroscopy, direct ligament repair can be performed using sutures and anchors.

Conclusions

In summary, the approach to AAI has evolved significantly: once considered to be an isolated disorder, it is now regarded as a complex syndrome often associated with ankle instability. This paradigm shift has been made possible thanks to advances in arthroscopy and the development of new concepts such as micro-instability. Arthroscopy not only allows a more accurate diagnosis, but also facilitates treatment of the different affected structures. In this way, it is possible to reduce the likelihood of symptoms recurrence compared with the situation observed when impingements were treated on an isolated basis. In order to more precisely establish the relationship between instability and anterior ankle impingement, it is essential to conduct and design new studies capable of providing more robust data and of further improving the management of this disorder.

Figuras

Figure 1. Bony impingement between the talus and tibia. A: ankle in plantar flexion; B: ankle in dorsiflexion showing impingement between the two osteophytes.

Figure 2. Anterior tibial osteophyte. A: in dorsiflexion the capsule separates from the osteophyte allowing its resection (B) through reaming.

Figure 3. Osteophyte due to chronic instability. A: the osteophyte forms a bone block extending over the anterior margin of the tibial plafond and the anterior aspect of the medial malleolus; B: arthroscopic view.

Figure 4. Soft tissue anterolateral impingement in a patient with concomitant anterior talofibular ligament injury who underwent arthroscopic repair associated with resection of the impingement.

Figure 5. Resection of the part closest to the talar cartilage can be completed with a basket forceps to minimize damage to the joint cartilage.

Figure 6. Groove produced by friction of the talar dome against Bassett's ligament, visible after resection of the latter. The ligament presented a partial tear and scar thickening.

Tablas

Información del artículo

Cita bibliográfica

Autores

Rodrigo Díaz Fernández

Unidad de Pie y Tobillo. Hospital de Manises. Valencia

Unidad de Pie y Tobillo. Vithas Valencia

Universidad Católica de Valencia San Vicente Mártir

Unidad de Pie y Tobillo. Hospital Quirónsalud Valencia

Vocal de Docencia de la SEMCPT

Ethical responsibilities

Conflicts of interest. The author Rodrigo Díaz Fernández declares the following conflict of interest: international consultant for Arthrex.

Financial support. This study has received no financial support.

Protection of people and animals. The authors declare that this research has not involved human or animal experimentation.

Data confidentiality. The author declares that the protocols of his work center referred to the publication of patient information have been followed.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The author declares that no patient data appear in this article.

Referencias bibliográficas

-

1Vega J, Dalmau-Pastor M. Editorial Commentary: Arthroscopic Treatment of Ankle Instability Is the Emerging Gold Standard. Arthroscopy. 2021;37(1):280-1.

-

2Sridharan SS, Dodd A. Diagnosis and Management of Deltoid Ligament Insufficiency. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2019;4(3).

-

3Vega J, Dalmau-Pastor M, Malagelada F, Fargues-Polo B, Peña F. Ankle Arthroscopy: An Update. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(16):1395-407.

-

4D’Hooghe P, Waldén M, Hägglund M, et al. Anterior ankle impingment syndrome is less frequent, but associated with a longer absence and higher re-injury rate compared to posterior syndrome: a prospective cohort study of 6754 male professional soccer players. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2022;30(12):4262-9.

-

5Vega J, Dalmau-Pastor M. Ankle Joint Microinstability: You Might Have Never Seen It but It Has Definitely Seen You. Foot Ankle Clin. 2023;28(2):333-44.

-

6Odak S, Ahluwalia R, Shivarathre DG, et al. Arthroscopic Evaluation of Impingement and Osteochondral Lesions in Chronic Lateral Ankle Instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36(9):1045-9.

-

7Van Dijk CN, Wessel RN, Tol JL, Maas M. Oblique radiograph for the detection of bone spurs in anterior ankle impingement. Skeletal Radiol. 2002;31(4):214-21.

-

8Niek van Dijk C. Anterior and posterior ankle impingement. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11(3):663-83.

-

9Chen X, Huang HQ, Duan XJ. Arthroscopic treatment of ankle impingement syndrome. Chin J Traumatol. 2023;26(6):311-6.

-

10Molinier F, Benoist J, Colin F, et al. Does antero-lateral ankle impingement exist? Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017;103(8S):S249-S252.

-

11Morris LH. Athlete's ankle. J Bone Joint Surg. 1943;25:220-3.

-

12McMurray TP. Footballer's ankle. J Bone Joint Surg. 1950;32(1):68-9.

-

13O'Donoghue DH. Impingement exostoses of the talus and tibia. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1957;39:835-52.

-

14Wolin I, Glassman F, Sideman S, Levinthal DH. Internal derangement of the talofibular component of the ankle. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1950;91(2):193-200.

-

15Ferkel RD, Karzel RP, Del Pizzo W, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of anterolateral impingement of the ankle. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(5):440-6.

-

16Ross KA, Murawski CD, Smyth NA, et al. Current concepts review: Arthroscopic treatment of anterior ankle impingement. Foot Ankle Surg. 2017;23(1):1-8.

-

17Rammelt S, Marx C. Managing Severely Malunited Calcaneal Fractures and Fracture-Dislocations. Foot Ankle Clin. 2020;25(2):239-56.

-

18Knupp M. The Use of Osteotomies in the Treatment of Asymmetric Ankle Joint Arthritis. Foot Ankle Int. 2017;38(2):220-9.

-

19Leiber-Wackenheim F. Anterior ankle impingement. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2025;111(1S):104063.

-

20Anastasio AT, Lau B, Adams S. Ankle Osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2024;32(16):738-46.

-

21Manoli A. Medial impingement of the ankle in athletes. Sports Health. 2010;2(6):495-502.

-

22Berberian WS, Hecht PJ, Wapner KL, Diverniero R. Morphology of tibiotalar osteophytes in anterior ankle impingement. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22(4):313-7.

-

23Cheng JC, Ferkel RD. The role of arthroscopy in ankle and subtalar degenerative joint disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;349(349):65-72.

-

24Vega J, Peña F, Golanó P. Minor or occult ankle instability as a cause of anterolateral pain after ankle sprain. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(4):1116-23.

-

25Van Dijk CN, Wessel RN, Tol JL, Maas M. Oblique radiograph for the detection of bone spurs in anterior ankle impingement. Skeletal Radiol. 2002;31(4):214-21.

-

26Katakura M, Odagiri H, Charpail C, et al. Arthroscopic treatment for anterolateral impingement of the ankle: Systematic review and exploration of evidence about role of ankle instability. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2022;108(7).

-

27Vega J, Malagelada F, Manzanares Céspedes MC, Dalmau-Pastor M. The lateral fibulotalocalcaneal ligament complex: an ankle stabilizing isometric structure. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(1):8-17.

-

28Vega J, Montesinos E, Malagelada F, et al. Microinstability of the Ankle. En: Lateral Ankle Instability: An International Approach by Ankle Instability Group. ESSKA-AFAS; 2018.

-

29Vega J, Malagelada F, Dalmau-Pastor M. Ankle microinstability: arthroscopic findings reveal four types of lesion to the anterior talofibular ligament's superior fascicle. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29(4):1294-303.

-

30Garth WP, Allman FL, Armstrong WS. Occult anterior subluxations of the shoulder in noncontact sports. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15(6):579-85.

-

31Freeman MA, Dean MR, Hanham IW. The etiology and prevention of functional instability of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1965;47(4):678-85.

-

32Guillo S, Bauer T, Lee JW, et al. Consensus in chronic ankle instability: aetiology, assessment, surgical indications and place for arthroscopy. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99(8 Suppl).

-

33Martin DE, Kaplan PA, Kahler DM, et al. Retrospective evaluation of graded stress examination of the ankle. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;328(328):165-70.

-

34Breitenseher MJ, Trattnig S, Kukla C, et al. MRI versus lateral stress radiography in acute lateral ankle ligament injuries. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1997;21(2):280-5.

-

35Frost SC, Amendola A. Is stress radiography necessary in the diagnosis of acute or chronic ankle instability? Clin J Sport Med. 1999;9(1):40-5.

-

36Frigg A, Frigg R, Hintermann B, et al. The biomechanical influence of tibio-talar containment on stability of the ankle joint. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(11):1355-62.

-

37Golightly YM, Hannan MT, Nelson AE, et al. Relationship of Joint Hypermobility with Ankle and Foot Radiographic Osteoarthritis and Symptoms in a Community-Based Cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019;71(4):538-44.

-

38Tol JL, Verheyen CPPM, van Dijk CN. Arthroscopic treatment of anterior impingement in the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(1):9-13.

-

39Dalmau-Pastor M, Vega J. Ankle Arthroscopy: No-Distraction and Dorsiflexion Allows Advanced Techniques. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(12):3171-2.

-

40Bassett FH 3rd, Gates HS 3rd, Billys JB, et al. Talar impingement by the anteroinferior tibiofibular ligament. A cause of chronic pain in the ankle after inversion sprain. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72(1):55-9.

-

41Yeo ED, Rhyu IJ, Kim HJ, et al. Can Bassettt’s ligament be removed? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(4):1236-42.

-

42Molloy S, Solan MC, Bendall SP. Synovial impingement in the ankle. A new physical sign. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(3):330-3.

-

43Liu SH, Nuccion SL, Finerman G. Diagnosis of anterolateral ankle impingement. Comparison between magnetic resonance imaging and clinical examination. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(3):389-93.

-

44Tol JL, van Dijk CN. Anterior ankle impingement. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11(2):297-310.

-

45Liu SH, Nuccion SL, Finerman G. Diagnosis of anterolateral ankle impingement. Comparison between magnetic resonance imaging and clinical examination. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(3):389-93.

-

46Robinson P, White LM, Salonen DC, et al. Anterolateral ankle impingement: mr arthrographic assessment of the anterolateral recess. Radiology. 2001;221(1):186-90.

-

47Nazarian LN, Gulvartian NV, Freeland EC, Chao W. Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Needle Fenestration and Corticosteroid Injection for Anterior and Anterolateral Ankle Impingement. Foot Ankle Spec. 2018;11(1):61-6.

Descargar artículo:

Licencia:

Este contenido es de acceso abierto (Open-Access) y se ha distribuido bajo los términos de la licencia Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND (Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional) que permite usar, distribuir y reproducir en cualquier medio siempre que se citen a los autores y no se utilice para fines comerciales ni para hacer obras derivadas.

Comparte este contenido

En esta edición

- Anterior ankle arthroscopy at its best

- Foot and ankle arthroscopy, a consolidated and expanding reality

- The history and current concepts of ankle arthroscopy

- Current status of anterior ankle impingement

- Arthroscopic treatment of chronic lateral ankle instability

- Managing osteochondral lesions of the talus with anterior ankle arthroscopy

- Role of arthroscopy in syndesmosis injuries

- Role of arthroscopy in the treatment of ankle fractures

- Anterior arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis

- The use of needle arthroscopy in the ankle

- The letter pi on the ankle

Más en PUBMED

Más en Google Scholar

Más en ORCID

Revista Española de Artroscopia y Cirugía Articular está distribuida bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional.