The history and current concepts of ankle arthroscopy

Historia y conceptos actuales de la artroscopia de tobillo

Resumen:

La artroscopia de tobillo ha evolucionado significativamente, pasando del método pionero inicial al método de distracción fija y, en la actualidad, al abordaje de dorsiflexión. El enfoque de dorsiflexión permite cambiar fácilmente entre dorsiflexión, posición neutra, flexión plantar y distracción en función de las necesidades de diferentes patologías. En el pasado, la distracción fija servía como herramienta de diagnóstico. Los avances en el diagnóstico por imagen eliminaron la necesidad de realizar artroscopias diagnósticas rutinarias. La distracción fija pone en peligro las estructuras neurovasculares, coloca al cirujano en una posición no ergonómica y no permite tratar eficazmente el pinzamiento y la inestabilidad. La versatilidad del método en dorsiflexión combina la seguridad con la posibilidad de elegir la posición articular óptima para abordar un defecto osteocondral (osteochondral defect –OCD–) del astrágalo, eliminar osteofitos, evaluar la laxitud de la sindesmosis o reparar la inestabilidad ligamentosa. Un menor riesgo de lesiones nerviosas, una mayor seguridad y opciones de tratamiento más flexibles y eficaces constituyen argumentos de peso que favorecen la técnica en dorsiflexión. Debe abandonarse la técnica de distracción fija como abordaje rutinario de la artroscopia anterior de tobillo.

Abstract:

Ankle arthroscopy has evolved significantly, transitioning from initial pioneering to the fixed distraction method and currently the dorsiflexion approach. The dorsiflexion approach allows easy switching between dorsiflexion, neutral, plantarflexion, and distraction, adapting to the needs of different pathologies. In the past fixed distraction served as a diagnostic tool. Advancements in imaging eliminated the need for routine diagnostic arthroscopy. Fixed distraction places neurovascular structures in danger, the surgeon in a non-ergonomic position and impingement and instability cannot be treated effectively. The versatility of the dorsiflexion method combines safety with the choice for the optimal joint position to approach an osteochondral defect (OCD) of the talus, remove osteophytes, test for syndesmosis laxity or repair ligament instability. A reduced risk of nerve injuries, better safety, more flexible and effective treatment options are overwhelming arguments that favors the dorsiflexion technique. The fixed distraction technique as a routine approach to anterior ankle arthroscopy should be abandoned.

Introduction

The origin of ankle arthroscopy traces back to the broader development of arthroscopy in the early 20th century. Nordentoft was the first, to perform arthroscopy of the knee(1), followed by Takagi in 1918 and his more detailed reports in 1939(2). Burman, in 1931, initially regarded the ankle joint as unsuitable for arthroscopy because of its complex and narrow anatomy(3). Nevertheless, Takagi systematically assessed the ankle arthroscopically in 1939, planting the first seeds for future developments.

It was not until after the success of knee arthroscopy in the 1950s and 1960s that minimally invasive techniques expanded to other joints, including the ankle. Watanabe published a series of 28 ankle arthroscopies in 1972, followed by Chen in 1976(4,5). However, the procedure remained in its infancy for years, facing technical limitations due to the ankle’s small joint space and anatomical challenges. Several publications in the 1980s gradually laid the groundwork for broader acceptance and refinement of the technique.

During the 1980s and 1990s, significant advancements were made in arthroscopic equipment, including better optics, specialized small-joint instruments, and improved visualization technologies. Yet, it is only over the last 30 years that ankle arthroscopy has truly evolved. In the past two decades especially, major progress has been achieved. Today, both anterior and posterior arthroscopic approaches to the ankle are possible.

Previously, fixed distraction was considered necessary for the approach to the ankle joint. Arthroscopy was also used as a diagnostic tool. However, with advances in imaging technology, routine diagnostic arthroscopy has largely been abandoned. Now, the arthroscope is viewed as a surgical tool, not as a diagnostic device.

Current indications for ankle arthroscopy include impingement removal, loose body retrieval, and treatment of osteochondral lesions. More advanced procedures, such as arthroscopic ligament reconstruction, arthrodesis, assisted fracture fixation and tendoscopic interventions around the Achilles tendon and peroneal tendons, are also increasingly common. Ankle arthroscopy has firmly established itself as the third most commonly performed arthroscopic procedure, following those of the knee and shoulder.

The use of ankle arthroscopy continues to rise. Werner et al.(6) demonstrated that its growth has outpaced that of other joints such as the knee, shoulder, and elbow. A Medtech 360 report further projected an annual growth rate of over 6.5% in the United States and over 11.5% in the Asia-Pacific region(7).

In the early 1990s, two distinct schools of thought emerged: the American and the European. In the USA, Jim Guhl popularized routine joint distraction during ankle arthroscopy, initially with skeletal distraction via external fixation and later evolving to fixed soft-tissue distraction(8). In Europe, at the same time, van Dijk and co-workers introduced the so-called dorsiflexion technique(9,10). Since then, these two approaches have coexisted — each influencing the development of ankle arthroscopy in different ways.

Fixed distraction vs. Dorsiflexion technique

In 2018, the Editor-in-Chief of The Journal of Arthroscopy highlighted a key controversy in ankle arthroscopy: the ongoing debate over whether the fixed distraction or dorsiflexion technique offers superior outcomes(11). This discourse became particularly pronounced between two prominent figures in the field — Dr. Richard Ferkel, a leading U.S.-based ankle surgeon, and Dr. Jordi Vega from Barcelona.

The debate originated with an editorial by Dr. Ferkel titled “Distraction is the Key to Success”, in which he emphasized the advantages of the fixed distraction technique for ankle arthroscopy(12). Dr. Vega, however, firmly contested this position, suggesting that continued reliance on fixed distraction was hindering innovation within the field. He advocated instead for the dorsiflexion method, pioneered by Van Dijk from Amsterdam, which he argued enables more advanced, third-generation procedures not feasible with traditional distraction techniques still commonly employed in the United States(13).

Dr. Ferkel responded robustly to these criticisms, asserting that his methods were contemporary and effective, dismissing the notion that they were not "third-generation" as "ridiculous"(14).

Over the years, both sides have continued to present strong arguments supporting their preferred techniques(15,16). Most recently, The Journal of Arthroscopy again provided a platform for Dr. Ferkel to defend fixed distraction, illustrating that the divide between these two approaches remains active(17).

As the field continues to evolve, a critical appraisal of both techniques is essential to guide surgical decision-making and optimize patient outcomes.

Comparative Overview of Fixed Distraction and Dorsiflexion Techniques

In order to understand the evolution of ankle arthroscopy it is important to consider the nuances of both fixed distraction and dorsiflexion approaches. In this section, we will review the principles, clinical applications, and outcomes associated with each method, aiming to provide a balanced perspective to guide technique selection in contemporary practice.

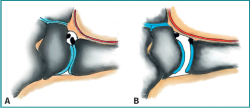

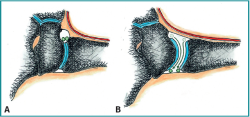

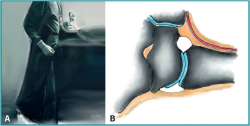

Initially developed by Jim Guhl, the fixed distraction technique was designed to enhance diagnostic capabilities and visualization of ankle joint pathologies, including posterior cartilage lesions and other posterior joint conditions, through an anterior approach(18). This method employs a mechanical device to apply consistent tension to the ankle joint, thereby increasing the intra-articular space and allowing improved access to posterior articular cartilage lesions and other posterior structures (Figure 1). Traditionally, this technique has been performed using small-diameter arthroscopes and instruments(18). Posterior pathologies, such as os trigonum syndrome, were addressed using the same setup with the addition of lateral and posterolateral portals(18). At that time, the posteromedial portal was considered a "no-go area"(8,18).

reacae.32284.fs2509021en-figure2.png

Figure 2. The dorsiflexion approach is named for the ankle position used during portal establishment and instrument insertion. The surgeon stabilizes against the sole of the affected foot (A). With the ankle held in dorsiflexion and saline infused, the anterior joint space naturally expands (B). The neurovascular structures are depicted in red and white.

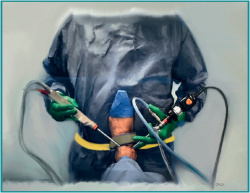

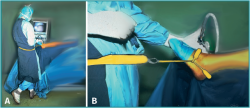

The dorsiflexion approach, is named for the ankle positioning (=dorsiflexion) used for introduction of arthroscope and instruments into the joint(9,10,19). By dorsiflexing the ankle and introducing saline, the anterior joint space naturally expands, facilitating entry of instruments (Figures 2A and 2B). Depending on the pathology and the procedural needs, the ankle can subsequently be positioned in dorsiflexion, neutral, plantarflexion, or even under distraction. Each pathology benefits from a tailored positioning for optimal treatment(10). This technique typically utilizes a 4 mm arthroscope along with larger-diameter shavers and instruments(10). To address posterior ankle pathology, rather than working from an anterior approach, van Dijk and co-workers developed a safe two-portal posterior approach with the patient positioned prone(20).

Safety and Flexibility of the Dorsiflexion Method

One of the most significant advantages of the dorsiflexion approach is the safe introduction of the arthroscope, shaver, and other instruments into the ankle joint. In dorsiflexion, key neurovascular structures — such as the superficial peroneal nerve — are lax and can more easily displace when instruments are introduced. In contrast, the fixed distraction technique places these structures under tension, similar to a tightened bowstring, rendering them less mobile and more vulnerable to iatrogenic injury. A small-diameter instrument introduced inadvertently onto a tensioned nerve is more likely to penetrate, damage, or even sever it. Conversely, a larger-diameter, blunter instrument, when introduced onto a relaxed nerve, is more likely to displace the structure without causing harm.

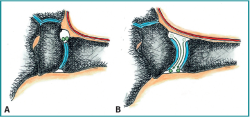

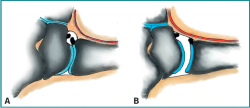

A second major advantage of the dorsiflexion approach is that dorsiflexion physically moves the neurovascular structures away from the joint space, further reducing the risk of injury(21) (Figure 3A). In contrast, fixed distraction draws these structures closer to the joint, increasing the potential for iatrogenic damage (Figure 3B). The enhanced safety profile of dorsiflexion has been supported by studies such as Tonogai’s, which demonstrated that the anterior safety zone is more than twice as large in dorsiflexion compared to distraction(22) (Figure 3A and 3B).

reacae.32284.fs2509021en-figure3.png

Figure 3. Dorsiflexion displaces neurovascular structures -depicted in red and white in these drawings- away from the joint, significantly minimizing the risk of iatrogenic injury (A). In contrast, fixed distraction draws these structures toward the joint, increasing their vulnerability (B). The anterior safety zone is more than twice as large with dorsiflexion compared to distraction (Tonogai, 2018). The neurovascular structures are depicted in red and white.

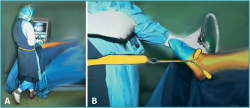

Beyond improved safety, dorsiflexion provides greater flexibility in addressing a wide range of intra-articular pathologies. Each pathology benefits from an optimized joint position during treatment. After instruments are safely introduced in dorsiflexion, the surgeon can adjust the ankle into dorsiflexion, neutral, or plantarflexion as needed. Distraction can also be applied selectively using a non-invasive distraction device(23) (Figure 4A and 4B). This approach enables surgeons to capitalize on the safety and ease of dorsiflexion during portal entry while retaining the option to apply distraction when additional joint space is required for posterior or central lesions(24).

reacae.32284.fs2509021en-figure4.png

Figure 4. The dorsiflexion technique provides enhanced versatility in addressing diverse intra-articular pathologies. Each condition may require a specific joint position for optimal access. Following portal establishment in dorsiflexion (see Fig. 2A), the ankle can be adjusted to dorsiflexion, neutral or plantarflexion. Distraction may be applied as needed using a non-invasive traction system (A and B).

Complications of Anterior Ankle Arthroscopy

While ankle arthroscopy has advanced considerably over recent decades, complication rates remain an important consideration when selecting the surgical approach. The dorsiflexion method is associated with a significantly lower complication rate compared to the fixed distraction technique.

Studies have reported complication rates ranging from 8% to 17% for ankle arthroscopies performed using fixed distraction, with an average rate of approximately 9%(25,26,27). Most of these complications are related to nerve injuries, attributable to the increased tension placed on neurovascular structures during distraction.

In contrast, a series of 1,305 consecutive ankle arthroscopies performed using the dorsiflexion technique demonstrated a significantly lower complication rate of only 3%(25). This improved safety profile is attributed to the safer positioning of the ankle during portal creation and the markedly enlarged anterior "safety zone" available for instrument insertion and manipulation.

Nerve injuries represent the most common complications in ankle arthroscopy and occur more frequently with fixed distraction. A nerve placed under tension and lying close to the portal site is less able to move aside when small-diameter instruments are introduced, increasing the likelihood of iatrogenic injury. Specific nerve injury risks associated with fixed distraction include the following nerve lesions. The incidence of superficial peroneal nerve lesions is approximately twice as high compared to dorsiflexion(25,26). The risk of sural nerve lesions is 12 times greater with fixed distraction(25,26). The risk of saphenous nerve injury is five times higher with fixed distraction(25,26).

These findings underscore the significant safety advantage of the dorsiflexion technique over fixed distraction in contemporary ankle arthroscopy.

The Role of Plantar Flexion

While the dorsiflexion approach facilitates safe and effective treatment of anterior ankle pathologies, plantar flexion plays a crucial role in accessing osteochondral defects of the talus (OCDs)(10). Plantar flexion enhances visualization and accessibility to the vast majority of talar dome OCD’s. Supporting this, Hirtler et al. demonstrated that forced plantar flexion significantly improves access to the talar surface, achieving levels comparable to those attained with fixed distraction techniques(24). The strategic combination of dorsiflexion for safe instrument insertion, forced plantar flexion for optimized talar access, and the selective use of soft-tissue distraction when necessary has consistently yielded excellent outcomes with minimal complications.

In the authors experience >95% of all osteochondral lesions can be approached and treated with debridement and bone marrow stimulation by means of an anterior approach making use of this forced plantar flexion position, and the selective use of the soft-tissue distraction device (Figure 4A and 4B). For the other <5% most posterior lesions the approach can be by means of a 2-portal posterior ankle arthroscopy approach with the patient prone.

Final Thoughts

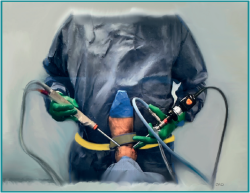

When employing a fixed distractor attached to the operating table, the surgeon's working position can be likened to sitting at a dinner table and reaching across for food from a neighboring plate (Figure 5). In contrast, operating within a flexible, non-fixed setup is akin to comfortably reaching one's own plate — a far more ergonomic, efficient, and intuitive way of working (Figure 6). Instruments are also less likely to break or bend when used in a flexible rather than a rigid setup, reducing intraoperative complications.

reacae.32284.fs2509021en-figure5.png

Figure 5. When a distractor is fixed to the operating table, it necessitates the surgeon to stand beside the patient’s foot. This positioning restricts access to the ergonomically favorable location at the distal end of the table. The situation is analogous to reaching across a dinner table for a neighbor’s plate—less efficient and more fatiguing than working directly in front of oneself.

In the following sections, we will discuss the current indications for ankle arthroscopy and critically examine both the fixed distraction and dorsiflexion methods. We will begin with diagnostic arthroscopy and the treatment of osteochondral defects, as these conditions historically provided the foundation for the development of the fixed distraction technique.

Diagnostic arthroscopy

In the early stages of arthroscopy's development, its primary role was diagnostic. Richard Ferkel describes the origins of the fixed distraction system: *"In 1984, Jim Guhl and I created the fixed distraction system because we recognized that we were missing a lot of pathology. A fixed, non-invasive distraction allows the surgeon to visualize the entire joint, not just a part of it"(14).

During those early years, three portals — anterolateral, anteromedial, and posterolateral — were commonly established to achieve comprehensive access to the ankle joint(28). Diagnostic arthroscopy was indicated for patients with unexplained ankle pain, joint stiffness, or to assess the extent of articular surface damage(8).

However, with the advent and refinement of non-invasive imaging modalities, such as MRI and CT, the need for routine diagnostic arthroscopy has disappeared. Today, non-invasive imaging is highly accurate and sufficient for diagnostic purposes, rendering the use of arthroscopy purely diagnostic in nature largely obsolete. Modern consensus now reflects this evolution: ankle arthroscopy is predominantly reserved as a therapeutic intervention rather than a diagnostic tool(29).

Despite this global trend, the fixed distraction technique — including diagnostic arthroscopy — remains in use in some regions, particularly in the United States(17). This includes applications such as diagnostic arthroscopy during ankle fracture management, arthroscopic ligament repair, second-look procedures after osteochondral defect (OCD) treatment, needle arthroscopy, and even asymptomatic osteophyte removal.

Diagnostic Arthroscopy in Ankle Fractures

Hintermann's landmark study reported that approximately 80% of patients with an ankle fracture also present with associated cartilage lesions(30). Similarly, Howard et al. observed a comparable incidence rate of 84%(31). These findings initially led to the widespread assumption that every ankle fracture should undergo diagnostic arthroscopy to assess intra-articular damage.

However, clinical practice patterns and outcomes do not support this approach. In the United States, only 1% of orthopedic surgeons routinely perform arthroscopy during ankle fracture management(32). Furthermore, even among those who do, there appears to be no significant impact on clinical outcomes(32). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis reinforced these findings, concluding that the presence or absence of cartilage lesions in the context of ankle fractures does not significantly influence functional outcomes(33).

Taken together, the available evidence suggests that routine diagnostic arthroscopy during ankle fracture surgery adds unnecessary complexity without providing meaningful benefit to the patient. Its use should therefore be carefully reconsidered.

Diagnostic Arthroscopy in Chronic Ankle Instability Repair

Patients with chronic ankle instability frequently exhibit asymptomatic cartilage damage, as demonstrated by several studies(34,35). However, similar to findings in ankle fracture cases, research has shown that the presence of asymptomatic cartilage lesions does not affect the clinical outcomes following chronic instability repairs(35,36). Diagnostic arthroscopy performed during ligament repair offers no demonstrable clinical advantage and may lead to unnecessary interventions.

Moreover, cartilage lesions associated with ankle fractures or chronic instability are typically superficial and clinically inconsequential. Highlighting these incidental findings to patients can provoke unnecessary anxiety without providing any meaningful therapeutic benefit.

Second-Look Arthroscopy After OCD Treatment

Second-look arthroscopy can be performed following microfracture treatment for osteochondral defects (OCD). In a study by Keun-Bae Lee, 20 patients underwent second-look arthroscopy one year after microfracture surgery(37). At that time, 80% of ankles still exhibited macroscopic fissures, and 35% demonstrated incomplete healing classified as ICRS grade III. Nevertheless, clinical outcomes were favorable, with 90% of patients achieving AOFAS scores over 80 points.

Similarly, a study involving 25 patients who underwent second-look arthroscopy at a mean of 3.6 years post-microfracture revealed that 36% had persistent incomplete cartilage healing (ICRS grade III)(38). Despite these findings, all patients demonstrated significant clinical improvement (p<0.001) and showed no radiographic progression of arthritis.

These observations underscore a critical point: clinical improvement occurs despite incomplete cartilage repair. The true source of persistent symptoms, when present, typically lies within the subchondral bone rather than the cartilage itself. Defects of the subchondral bone plate should be evaluated through MRI or CT imaging, rather than arthroscopy. Superficial cartilage defects, in the absence of underlying bone pathology, are clinically insignificant and do not require intervention. Moreover, attempting to treat such lesions may unnecessarily increase the risk of complications.

Needle Arthroscopy

Needle arthroscopy, also referred to as nanoscopy, utilizes a 2.3 mm disposable arthroscope and can be performed under local anesthesia in an outpatient setting. While studies have demonstrated that ankle arthroscopy can be safely and effectively performed with local anesthesia(39), its widespread adoption has not materialized as initially anticipated.

The use of the nanoscope for routine cartilage evaluation is highly questionable. For instance, superficial cartilage lesions—such as "tram track" markings—hold no clinical relevance, as they do not penetrate the subchondral bone. Highlighting these findings to your patient can unnecessarily increase anxiety. Patients may worry excessively, asking questions like, “Doctor, is it really safe to walk without cartilage?”

Similar concerns arise with second-look needle arthroscopy following cartilage repair procedures. At one year post-treatment, 80% of patients still show repair cartilage that appears soft, cracked, or fissured, despite excellent clinical outcomes(37). Even at four years, 35% of patients with good clinical results still exhibit incomplete cartilage healing (ICRS grade III)(38). These findings can lead patients to attribute minor symptoms, such as occasional stiffness or slight discomfort, to structural abnormalities that do not require further intervention, placing them at risk of unnecessary worry—and potentially unnecessary procedures.

Although the nanoscope has been advocated for intra-articular delivery of injectables such as hyaluronic acid, its reported accuracy is below 90%(40). Furthermore, the single-use nanoscope represents a solution in search of a problem: it was developed without a clearly defined clinical need. The disposable instrument sets accompanying these devices raise significant environmental concerns(41) and contribute to increasing healthcare costs without offering clear patient benefit.

Asymptomatic Spurs and Osteophytes

Diagnostic arthroscopy carries approximately a 20% chance of detecting a spur or osteophyte in an otherwise healthy, asymptomatic individual(42). Research has shown that one in five people aged 20–40 years exhibit spurs or osteophytes without any associated symptoms(42). Furthermore, asymptomatic osteophytes are found in 33% of patients with chronic ankle instability and in 50% of those with talar osteochondral defects (OCD)(43).

Although spur removal may yield a “clean” postoperative X-ray, this result is often temporary, as osteophytes tend to recur(44,45). Importantly, these asymptomatic spurs are generally harmless and may even contribute positively by stabilizing the joint. In rare cases where spurs become symptomatic, removal can still be considered at a later stage.

Unnecessary removal of asymptomatic spurs introduces risks without offering real benefit. It can lead to complications such as arthrofibrosis, particularly if the joint is immobilized after combined procedures like spur removal with ligament repair.

Conclusion

In the past, when non-invasive diagnostic techniques were less developed, arthroscopy with fixed distraction played an important role in diagnosis. However, advancements in imaging have made non-invasive diagnostics far more accurate, eliminating the need for routine diagnostic arthroscopy. Today, arthroscopy is rightly viewed solely as a therapeutic tool to perform surgical interventions.

Multiple studies have shown that diagnostic arthroscopy in cases of ankle fractures, chronic instability repairs, or asymptomatic osteophyte removal does not improve patient outcomes. Similarly, superficial cartilage damage—whether observed after OCD treatment or via needle arthroscopy—does not require intervention unless it extends into the subchondral bone. Monitoring these conditions is better achieved through non-invasive methods such as MRI or CT.

Routine diagnostic arthroscopy by means of fixed distraction introduces unnecessary risks and costs without adding clinical benefit. It should therefore be avoided.

Osteochondral defects (OCD)

In the eighties and nineties of last century it was believed that fixed distraction was mandatory for the treatment of talar OCD. Currently we know that the dorsiflexion method provides equal or better access to the vast majority of talar OCD.

History and evolution of treatment of talar OCD

Bone marrow stimulation (BMS) with microfracture as a treatment for OCD was introduced by Steadman over 25 years ago. Since then, various cartilage restoration techniques have been developed, primarily aiming to regenerate hyaline cartilage. These approaches include biological methods such as Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (ACI), Matrix-Associated Chondrocyte Implantation (MACI), Autologous Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis (AMIC), and the use of scaffolds or juvenile cartilage.

Where do we stand today?

Two recent systematic reviews have concluded that no single treatment shows clinical superiority(46,47). The pooled success rate of 82% supports Bone Marrow Stimulation (BMS) as the first-line treatment(46). In fact, a survey of 1,800 surgeons found that 78% indeed prefer BMS as their treatment of choice(48).

Several long-term studies confirm that microfracture results are maintained over time. Van Bergen's study, with 8–20 years of follow-up, reported 78% good-to-excellent results and an 88% sport resumption rate. Joint space narrowing occurred in only 4% of cases(49). Corr et al. showed a 93% survival rate and 86% return to sport at 10–12 years(50). Park et al. demonstrated a 97% survival rate at 10–19 years(51). A systematic review covering six studies found a mean pooled AOFAS score of 84 at an average 13-year follow-up, with 78% of patients participating in sports and joint space narrowing seen in just 4.5% of cases(52).

Asymptomatic osteophytes were found in approximately 30% of cases in these long-term follow-up studies, though it remains unclear whether they developed postoperatively or were already present before surgery(52). It is known that 50% of patients with talar OCDs initially present with osteophytes(43), and once removed, these osteophytes tend to return in 84% of cases(45). Therefore, the 30% rate of asymptomatic osteophytes in long-term follow-up does not represent arthrosis but likely reflects pre-existing or stabilizing bone changes.

These long-term outcomes confirm that BMS with microfracture remains an effective and reliable treatment over time. Other cartilage restoration techniques currently lack comparable long-term follow-up data, and it remains to be seen whether they will outperform BMS.

Bone Marrow Stimulation remains minimally invasive, cost-effective, technically straightforward, and associated with low complication rates—offering both short- and long-term satisfactory results.

Surgical approach for talar OCD treatment

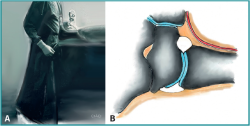

The surgical approach to OCDs can be anterior, posterior, or via malleolar osteotomy, with a plantar-flexed CT scan often aiding in decision-making. Based on my 35 years of experience treating talar OCDs, over 95% of microfracture cases have been managed through an anterior arthroscopic approach, making use of the dorsiflexion method without fixed distraction. Forced plantar flexion generally allows sufficient access to the lesion. A preoperative CT scan with forced plantar flexion (Figure 7) can help plan the approach. In some cases, applying non-invasive distraction can provide easier access when needed, especially when switching between dorsiflexion and distraction intraoperatively.

reacae.32284.fs2509021en-figure7.png

Figure 7. A preoperative CT scan performed with the ankle in forced plantarflexion can be a valuable tool in surgical planning. The sagittal image on the left reveals a posteromedially located osteochondral defect (OCD). In plantarflexion on the right, the same view illustrates the intraoperative position the surgeon will achieve. Two key anatomical changes occur: 1) A gap forms between the anterior distal tibia and the talus, improving access to the posterior joint space and the OCD; 2)The OCD shifts anteriorly. Using the anterior rim of the distal tibia as a reference easily identifiable intraoperatively.

The treatment of osteochondral defects historically provided the foundation for the development of the fixed distraction technique. The dorsiflexion technique, however, provides better access to these defects since it is more versatile. It combines the safety of the approach and provides the options of soft tissue distraction or plantar flexion or even a combination of these positions. This tailormade approach- which includes preoperative planning- is beneficial for the treatment of talar OCD.

While the dorsiflexion approach facilitates safe and effective introduction of instruments, plantar flexion plays a crucial role in accessing osteochondral defects of the talus (OCDs)(10,21). Plantar flexion enhances visualization and accessibility to the vast majority of talar dome OCD’s. Supporting this, Hirtler et al. demonstrated that forced plantar flexion significantly improves access to the talar surface, achieving levels comparable to those attained with fixed distraction techniques(24).

The strategic combination of dorsiflexion for safe instrument insertion, forced plantar flexion for optimized talar access, and the selective use of soft-tissue distraction when necessary has consistently yielded excellent outcomes with minimal complications.

Anterior ankle impingement

The removal of tibial and talar osteophytes is most easily accomplished with the ankle in dorsiflexion, as this position opens the anterior compartment and the gutters (Figure 3A). In contrast, joint distraction causes the gutters to close, making osteophyte removal more difficult.

Anterior ankle impingement is the most common indication for ankle arthroscopy, and arthroscopic treatment delivers excellent results when no joint space narrowing is present. Arthroscopic removal of osteophytes or soft tissue impediments yields 83% good-to-excellent outcomes at 5–8 years follow-up for grade 0–I lesions. In cases of osteophytes secondary to arthritis (grade II lesions), good-to-excellent results are achieved in 50% of cases(44).

A more recent systematic review confirmed these findings, reporting an 81% success rate for arthroscopic removal and an average return-to-sport time of just 8 weeks(53).

Osteophytes tend to recur after resection, with recurrence rates ranging from 76% to 84%(44,45). However, despite recurrence, patients typically do not experience a return of symptoms. Osteophytes contribute to joint stabilization, and studies of 670 ankle specimens from individuals aged 20–40 years showed that 21% had osteophytes, indicating that 1 in 5 asymptomatic young adults have osteophytes(42).

Osteophytes are located within the joint capsule attachment. These osteophytes can be easily identified and removed during arthroscopy with the ankle in dorsiflexion, and detachment of the joint capsule is not necessary for access. Fixed distraction is not suitable for the treatment of anterior impingement

Ligament repair

In order to address the question on the best approach we will first address the difference between laxity and instability. An anterior drawer test greater than 2 mm indicates ankle laxity. However, most lax ankles remain asymptomatic, as laxity itself is just a sign and not a symptom—instability is. Instability refers to recurrent episodes of the ankle giving way. Functional instability involves giving way despite a stable ankle, whereas mechanical instability occurs when a lax ankle is prone to giving way.

Two meta-analyses published in 2020 found that arthroscopic ligament repair offered significant advantages over open repair, including better AOFAS scores, lower pain levels, and fewer wound complications(54,55). A more recent meta-analysis in 2021 confirmed these findings, demonstrating superior clinical outcomes for arthroscopic repair, with higher AOFAS and Karlsson scores, lower pain scores, and fewer wound complications. Both techniques showed similar results on stress X-rays(56). While most patients with instability also have asymptomatic cartilage damage, as discussed earlier, studies show no difference in outcomes between patients with or without chondral lesions. Therefore, performing diagnostic arthroscopy during ligament repair does not offer any clinical advantage.

It is clear that ligament tightening can only be effectively performed without joint distraction, as distraction would compromise the shortening of the ligament needed during repair.

Syndesmotic assessment

Similar to assessing lateral ligament laxity, evaluating syndesmotic laxity under distraction is problematic. In distraction, the syndesmosis cannot open up, making this a less reliable method for assessment(57). While a soft tissue distractor can be applied to facilitate entry into the joint with a probe or other device, distraction must be released in order to accurately test syndesmotic stability.

Loose bodies

Loose body removal is straightforward when the ankle is held in dorsiflexion. However, during distraction, loose bodies may migrate to the posterior aspect of the joint, making them significantly more difficult to retrieve (Figure 8). This phenomenon applies not only to loose bodies but also to debris such as bony fragments generated during osteophyte removal.

Conclusion

Ankle arthroscopy has evolved significantly, transitioning from initial pioneering to the fixed distraction method and currently the dorsiflexion approach. The dorsiflexion technique is named for the initial joint position during instrument insertion. Once the instruments are introduced in dorsiflexion, the ankle can be positioned in dorsiflexion, neutral, or plantarflexion, depending on the pathology being addressed. This flexibility provides optimal access for different conditions. If needed, distraction can still be applied using a non-invasive device, combining the safety and ease of dorsiflexion with the option to gain additional space for central or posterior pathologies.

Fixed distraction forces the anteromedial portal medially, impairing visualization of the lateral gutter. It places the surgeon in a non-ergonomic position beside the patient and, due to the rigid setup and delicate instruments, increases the risk of bending or breaking tools. The dorsiflexion method avoids these disadvantages.

As to the treatment of various pathologies, anterior ankle impingement is much more effectively treated in dorsiflexion. Distraction places nerves and vessels at risk by pulling them into the joint space and directly over osteophytes, increasing the chance of neurovascular injury. In addition, with fixed distraction, loose bodies and debris tend to migrate posteriorly, making retrieval more difficult and hazardous. Ligaments cannot be effectively repaired under distraction, and syndesmotic laxity cannot be reliably assessed in a distracted position.

Historically, when non-invasive diagnostic techniques were limited, arthroscopy under fixed distraction served a diagnostic role. However, with modern advancements in imaging, routine diagnostic arthroscopy is no longer necessary. Today, the arthroscope should be viewed solely as a tool for surgical intervention—not for routine diagnosis.

This leaves treatment of talar osteochondral defects (OCDs) as the only remaining reasonable indication for distraction. Yet even for OCDs, the dorsiflexion method offers greater safety and flexibility, allowing easy transitions between dorsiflexion, plantarflexion, and distraction, without the downsides of fixed systems. Over 95% of talar OCDs can be successfully treated without the need for fixed joint distraction, as described in this chapter.

As for the treatment of posterior ankle pathology historically these where treated by an anterior approach through a distracted joint. Instead of trying to resolve posterior ankle pathology from an anterior approach, a safe 2 portal posterior approach with the patient in a prone position was developed and widely implemented(20). Tendoscopic interventions around the Achilles tendon and peroneal tendons, are also increasingly common.

Ankle arthroscopy has firmly established itself as the third most commonly performed arthroscopic procedure, following those of the knee and shoulder. The overwhelming advantages of the dorsiflexion technique—including reduced nerve injury risk, enhanced safety, more flexible access, and more effective procedures—strongly support its adoption. The fixed distraction technique for anterior ankle arthroscopy should be abandoned.

Figuras

Figure 1. Fixed distraction employs a mechanical device to exert continuous traction on the joint. The setup consists of a traction apparatus affixed to the operating table, along with a proximal thigh support.

Figure 2. The dorsiflexion approach is named for the ankle position used during portal establishment and instrument insertion. The surgeon stabilizes against the sole of the affected foot (A). With the ankle held in dorsiflexion and saline infused, the anterior joint space naturally expands (B). The neurovascular structures are depicted in red and white.

Figure 3. Dorsiflexion displaces neurovascular structures -depicted in red and white in these drawings- away from the joint, significantly minimizing the risk of iatrogenic injury (A). In contrast, fixed distraction draws these structures toward the joint, increasing their vulnerability (B). The anterior safety zone is more than twice as large with dorsiflexion compared to distraction (Tonogai, 2018). The neurovascular structures are depicted in red and white.

Figure 4. The dorsiflexion technique provides enhanced versatility in addressing diverse intra-articular pathologies. Each condition may require a specific joint position for optimal access. Following portal establishment in dorsiflexion (see Fig. 2A), the ankle can be adjusted to dorsiflexion, neutral or plantarflexion. Distraction may be applied as needed using a non-invasive traction system (A and B).

Figure 5. When a distractor is fixed to the operating table, it necessitates the surgeon to stand beside the patient’s foot. This positioning restricts access to the ergonomically favorable location at the distal end of the table. The situation is analogous to reaching across a dinner table for a neighbor’s plate—less efficient and more fatiguing than working directly in front of oneself.

Figure 6. Ergonomic positioning is achieved when the surgeon stands at the distal end of the operating table. This setup not only enhances comfort and control but also reduces the risk of instrument breakage or deformation, as tools are used within a more flexible and forgiving working environment.

Figure 7. A preoperative CT scan performed with the ankle in forced plantarflexion can be a valuable tool in surgical planning. The sagittal image on the left reveals a posteromedially located osteochondral defect (OCD). In plantarflexion on the right, the same view illustrates the intraoperative position the surgeon will achieve. Two key anatomical changes occur: 1) A gap forms between the anterior distal tibia and the talus, improving access to the posterior joint space and the OCD; 2)The OCD shifts anteriorly. Using the anterior rim of the distal tibia as a reference easily identifiable intraoperatively.

Información del artículo

Cita bibliográfica

Autores

Niek van Dijk

Departamento de Cirugía Ortopédica. Universidad de Ámsterdam. Amsterdam University Medical Center, sede AMC. Países Bajos

Unidad de Tobillo Centro Médico de Excelencia de la FIFA Ripoll-DePrado Sport Clinic. Madrid. España

Unidad de Tobillo Centro Médico de Excelencia de la FIFA Clínica do Dragão. Porto. Portugal

Departamento de Ortopedia. Casa di Cura San Rossore. Pisa. Italia

Colaboración para la Salud y la Seguridad en el Deporte de Ámsterdam (ACHSS)

Ethical responsibilities

Conflicts of interest. The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Financial support. This study has received no financial support.

Protection of people and animals. The authors declare that this research has not involved human or animal experimentation.

Data confidentiality. The authors declare that the protocols of their work centre referred to the publication of patient information have been followed.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Referencias bibliográficas

-

1Nordentoft S. Ueber Endoskopie geschlossener Kavitäten mittels Trokarendoskops Zentralbl Chir. 1912;39:95-7.

-

2Takagi K. The arthroscope. J Jpn Orthop Assoc. 1939;14:359-441.

-

3Burman MS. Arthroscopy of direct visualization of joints. An experimental cadaver study. J Bone Joint Surg. 1931;13:669-95.

-

4Watanabe M. Sefloc Arthrocope (Watanabe no. 24 arthroscope). Monograph. Tokyo: Teishin Hospital; 1972.

-

5Chen DS, Wertheimer SJ. Centrally located osteochondral fracture of the talus. J Foot Surg. 1992;31:134-40.

-

6Werner BC, Burrus MT, Park JS, et al. Trends in Ankle Arthroscopy and Its Use in the Management of Pathologic Conditions of the Lateral Ankle in the United States: A National Database Study. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(7):1330-7.

-

7Medtech 360. Markets for Arthroscopy Devices. Disponible en: http://mrg.net/Products-and-Services/Syndicated.

-

8Guhl J. Ankle arthroscopy Schlack Inc.; 1992.

-

9Van Dijk CN, Scholte D. Arthroscopy of the ankle joint. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(1):90-6.

-

10Van Dijk CN. Ankle Arthroscopy: Techniques Developed by the Amsterdam Foot and Ankle School. Springer; 2014.

-

11Lubowitz JH, Brand JC, Rossi MJ. Letters to the Editor Highlight Current Controversies. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(2):297-9.

-

12Ferkel RD. Editorial commentary: Ankle arthroscopy: Correct portals and distraction are the keys to success. Arthroscopy. 2016;32:1375-6.

-

13Vega J, Dalmau-Pastor M. Ankle arthroscopy: No-distraction and dorsiflexion technique is the key for ankle arthroscopy evolution. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(5):1380-2.

-

14Ferkel RD. Author reply to “‘Ankle arthroscopy: No-distraction and dorsiflexion technique is the key for ankle arthroscopy evolution”. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(5):1382-3.

-

15Ferkel RD. Editorial commentary: Osteochondral lesions of the talus—Are we going the wrong way? Arthroscopy. 2017;33:2246-7.

-

16Dalmau-Pastor M, Vega J. Ankle Arthroscopy: No-Distraction and Dorsiflexion Allows Advanced Techniques. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(12):3171-2.

-

17Connelly J, Ferkel RD. Ankle Arthroscopy: Correct Portals and Noninvasive Distraction. Arthroscopy. 2021;37(4):1066-7.

-

18Ferkel RD. Foot and Ankle Arthroscopy. Second Edition. Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

-

19Van Dijk CN, van Bergen CJA. Advancements in ankle arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(11):635-46.

-

20Van Dijk CN, Scholten PE, Krips R. A 2-portal endoscopic approach for diagnosis and treatment of posterior ankle pathology. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(8):871-6.

-

21De Leeuw PA, Golanó P, Clavero JA, van Dijk CN. Anterior ankle arthroscopy, distraction or dorsiflexion? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(5):594-600.

-

22Tonogai I, Hayashi F, Tsuruo Y, Sairyo K. Distance Between the Anterior Distal Tibial Edge and the Anterior Tibial Artery in Distraction and Nondistraction During Anterior Ankle Arthroscopy: A Cadaveric Study. Foot Ankle Int. 2018;39(1):113-8.

-

23Van Dijk CN, Verhagen RA, Tol HJ. Technical note: Resterilizable noninvasive ankle distraction device. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(3):E12.

-

24Hirtler L, Schuh R. Accessibility of the Talar Dome-Anatomic Comparison of Plantarflexion Versus Noninvasive Distraction in Arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(2):573-80.

-

25Zengerink M, van Dijk CN. Complications in ankle arthroscopy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(8):1420-31.

-

26Ferkel RD, Heath DD, Guhl JF. Neurological complications of ankle arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:200-8.

-

27Galla M, Lobenhoffer P. Technique and results of arthroscopic treatment of posterior ankle impingement. Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;17:79-84.

-

28Ferkel RD. Ankle and Foot Arthroscopy, Contemporary Approach to Diagnosis and Treatment. Smith & Nephew Inc.; 2009. Disponible en: http://www.ankle-arthroscopy.co.uk.

-

29Shah R, Bandikalla VS. Role of Arthroscopy in Various Ankle Disorders. Indian J Orthop. 2021;55(2):333-41.

-

30Hintermann B, Regazzoni P, Lampert C, et al. Arthroscopic findings in acute fractures of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(3):345-51.

-

31Howard S, Hoang V, Sagers K, et al. Identifying Intra-Articular Pathology With Arthroscopy Prior to Open Ankle Fracture Fixation. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2021;3(1):e177-e181.

-

32Yasui Y, Shimozono Y, Hung CW, et al. Postoperative Reoperations and Complications in 32,307 Ankle Fractures With and Without Concurrent Ankle Arthroscopic Procedures in a 5-Year Period Based on a Large U.S. Healthcare Database. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2019;58(1):6-9.

-

33Darwich A, Adam J, Dally FJ, et al. Incidence of concomitant chondral/osteochondral lesions in acute ankle fractures and their effect on clinical outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2021;141(1):63-74.

-

34Hintermann B, Boss A, Schäfer D. Arthroscopic Findings in Patients with Chronic Ankle Instability. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(3):402-9.

-

35Okuda R, Kinoshita M, Morikawa J, et al. Arthroscopic Findings in Chronic Lateral Ankle Instability: Do Focal Chondral Lesions Influence the Results of Ligament Reconstruction? Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(1):35-42.

-

36Yasui Y, Murawski CD, Wollstein A, Kennedy JG. Reoperation rates following ankle ligament procedures performed with and without concomitant arthroscopic procedures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(6):1908-15.

-

37Lee KB, Bai LB, Yoon TR, et al. Second-look arthroscopic findings and clinical outcomes after microfracture for osteochondral lesions of the talus. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37 Suppl 1:63S-70S.

-

38Yang HY, Lee KB. Arthroscopic Microfracture for Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: Second-Look Arthroscopic and Magnetic Resonance Analysis of Cartilage Repair Tissue Outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg. 2019;102(1):10-20.

-

39Eriksson E. Arthroscopic surgery and local anaesthesia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1997;5(4):205.

-

40Stornebrink T, Stufkens SAS, Mercer NP, et al. Can bedside needle arthroscopy of the ankle be an accurate option for intra-articular delivery of injectable agents? World J Orthop. 2022;13(1):78-86.

-

41Van Egmond PW, Meester RJ, van Dijk CN. From big hands to green fingers: it is time for a change. J ISAKOS. 2023;8(4):213-5.

-

42Talbot CE, Knapik DM, Miskovsky SN. Prevalence and location of bone spurs in anterior ankle impingement: A cadaveric investigation. Clin Anat. 2018;31(8):1144-50.

-

43Wang DY, Jiao C, Ao YF, et al. Risk Factors for Osteochondral Lesions and Osteophytes in Chronic Lateral Ankle Instability: A Case Series of 1169 Patients. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8(5):2325967120922821.

-

44Van Dijk CN, Tol JL, Verheyen CC. A prospective study of prognostic factors concerning the outcome of arthroscopic surgery for anterior ankle impingement. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(6):737-45.

-

45Walsh SJ, Twaddle BC, Rosenfeldt MP, Boyle MJ. Arthroscopic treatment of anterior ankle impingement: a prospective study of 46 patients with 5-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(11):2722-6.

-

46Dahmen J, Lambers KTA, Reilingh ML, et al. No superior treatment for primary osteochondral defects of the talus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(7):2142-57.

-

47Anwander H, Vetter P, Kurze C, et al. Evidence for operative treatment of talar osteochondral lesions: a systematic review. EFORT Open Rev. 2022;7(7):460-9.

-

48Guelfi M, DiGiovanni CW, Calder J, et al. Large variation in management of talar osteochondral lesions among foot and ankle surgeons: results from an international survey. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29(5):1593-603.

-

49Van Bergen CJ, Kox LS, Maas M, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of osteochondral defects of the talus: outcomes at eight to twenty years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(6):519-25.

-

50Corr D, Raikin J, O'Neil J, Raikin S. Long-term Outcomes of Microfracture for Treatment of Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus. Foot Ankle Int. 2021;42(7):833-40.

-

51Park JH, Park KH, Cho JY, et al. Bone Marrow Stimulation for Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: Are Clinical Outcomes Maintained 10 Years Later? Am J Sports Med. 2021;49(5):1220-6.

-

52Rikken QGH, Dahmen J, Stufkens SAS, Kerkhoffs GMMJ. Satisfactory long-term clinical outcomes after bone marrow stimulation of osteochondral lesions of the talus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29(11):3525-33.

-

53Gianakos AL, Ivander A, DiGiovanni CW, Kennedy JG. Outcomes After Arthroscopic Surgery for Anterior Impingement in the Ankle Joint in the General and Athletic Populations: Does Sex Play a Role? Am J Sports Med. 2021;49(10):2834-42.

-

54Zhi X, Lv Z, Zhang C, et al. Does arthroscopic repair show superiority over open repair of lateral ankle ligament for chronic lateral ankle instability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2020;15(1):355.

-

55Brown AJ, Shimozono Y, Hurley ET, Kennedy JG. Arthroscopic versus open repair of lateral ankle ligament for chronic lateral ankle instability: a meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(5):1611-8.

-

56Moorthy V, Sayampanathan AA, Yeo NEM, Tay KS. Clinical Outcomes of Open Versus Arthroscopic Broström Procedure for Lateral Ankle Instability: A Meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2021;60(3):577-84.

-

57Lubberts B, Guss D, Vopat BG, et al. The effect of ankle distraction on arthroscopic evaluation of syndesmotic instability: A cadaveric study. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2017;50:16-20.

Descargar artículo:

Licencia:

Este contenido es de acceso abierto (Open-Access) y se ha distribuido bajo los términos de la licencia Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND (Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional) que permite usar, distribuir y reproducir en cualquier medio siempre que se citen a los autores y no se utilice para fines comerciales ni para hacer obras derivadas.

Comparte este contenido

En esta edición

- Anterior ankle arthroscopy at its best

- Foot and ankle arthroscopy, a consolidated and expanding reality

- The history and current concepts of ankle arthroscopy

- Current status of anterior ankle impingement

- Arthroscopic treatment of chronic lateral ankle instability

- Managing osteochondral lesions of the talus with anterior ankle arthroscopy

- Role of arthroscopy in syndesmosis injuries

- Role of arthroscopy in the treatment of ankle fractures

- Anterior arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis

- The use of needle arthroscopy in the ankle

- The letter pi on the ankle

Más en PUBMED

Más en Google Scholar

Revista Española de Artroscopia y Cirugía Articular está distribuida bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional.