Arthroscopic treatment of chronic lateral ankle instability

Tratamiento artroscópico de la inestabilidad lateral crónica de tobillo

Resumen:

El esguince de tobillo es una de las patologías más frecuentes en los servicios de urgencias hospitalarias y atención primaria. Entre un 10 y un 30% de los pacientes pueden evolucionar a una inestabilidad lateral crónica del tobillo (ILCT). Existe consenso acerca de que, tras el fracaso de 6 meses de tratamiento conservador, debe plantearse la opción quirúrgica.

Los procedimientos quirúrgicos han evolucionado desde las técnicas abiertas hasta la artroscopia, que permite una recuperación más rápida y una menor tasa de complicaciones. En relación con el tratamiento artroscópico de la inestabilidad de tobillo, el punto clave del tratamiento quirúrgico de la ILCT es la elección de un procedimiento quirúrgico adecuado para cada paciente. El objetivo de esta revisión es valorar la evidencia científica disponible.

Abstract:

Ankle sprains are among the most frequent conditions seen in hospital emergency departments and primary care. Between 10-30% of patients may progress to chronic lateral ankle instability (CLAI). There is consensus that surgery should be considered after failure of 6 months of conservative treatment.

Surgical procedures have evolved from open techniques to arthroscopy, which allows for faster recovery and a lower complications rate. In relation to the arthroscopic treatment of ankle instability, the key point in the surgical management of CLAI is the choice of an appropriate surgical procedure for each patient. The present review assesses the available scientific evidence in this regard.

Introduction

Ankle sprains are among the most frequent conditions seen in hospital emergency departments and primary care. Although it is difficult to obtain an accurate estimate of how many ankle sprains occur each year, data from the United States indicate that between 2-7 sprains/1000 people, or 2 million sprains in total, are recorded each year(1). In terms of the associated costs, we see that each sprain has a treatment cost of $1,029 ($723-1,457), yielding a figure of $2.05 billion spent each year in the United States due to ankle sprains(1). If we transfer these figures to Spain, we could be talking about 300,000 sprains a year and a cost associated with their treatment of 308 million euros annually. This amount is likely to be lower, since we can estimate that medical costs in the United States are probably higher than in Spain; nevertheless, it still represents a very significant consumption of health and social care resources due to this disorder.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of ankle sprains is that the general population perceives them as banal and minor injuries. After injury, the initial treatment is usually of a conservative nature, involving an appropriate rehabilitation protocol. Despite this, such treatment will fail in 10-30% of all patients, resulting in chronic lateral ankle instability (CLAI) that may require surgical treatment(2).

Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of CLAI have considerably improved the ability of clinicians to deal with this disorder. Conservative management remains the first line of therapy for CLAI in most cases. Rehabilitation programs have evolved, incorporating neuromodulation and specific muscle strengthening exercises. A recent meta-analysis has shown that multimodal rehabilitation programs, combining proprioceptive exercises and functional strengthening, significantly improve ankle stability and reduce the risk of recurrence(3).

In cases where conservative treatment proves ineffective, surgery is the next option. Surgical procedures have evolved from open techniques to arthroscopy, which allows for faster recovery and a lower complications rate(4). The key point in the surgical treatment of CLAI is the choice of a surgical procedure suited to each patient. The present review examines the available scientific evidence in this regard.

An anatomical reminder

The lateral collateral ligament of the ankle is made up of three ligaments: the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL), and the posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL). Of these, the most clinically relevant ligament is the ATFL, since it is the first ligament to be injured in an inversion ankle sprain, followed by the CFL. The ATFL is the weakest and most frequently injured ligament in ankle sprains, while the CFL is involved in 50-75% of such injuries and the PTFL in < 10%(5,6).

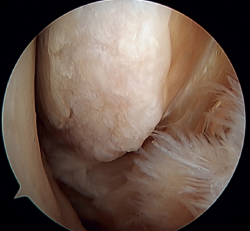

reacae.32284.fs2507015en-figure1.png

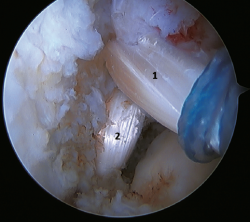

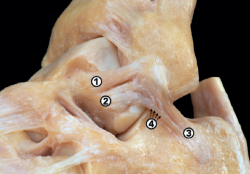

Figure 1. Anatomical dissection showing the lateral fibulotalocalcaneal complex of the ankle. 1: superior fascicle of the anterior talofibular ligament; 2: inferior fascicle of the anterior talofibular ligament; 3: calcaneofibular ligament; 4: connecting fibers between the inferior fascicle of the anterior talofibular ligament and the calcaneofibular ligament. Image reproduced with permission: Hong CC, Lee JC, Tsuchida A, et al. Individual fascicles of the ankle lateral ligaments and the lateral fibulotalocalcaneal ligament complex can be identified on 3D volumetric MRI. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31(6):2192-8.

In recent years there have been many changes in the anatomical description of these ligaments (Figure 1). In addition to intra-articular connections between the three ligaments(7), the most relevant findings refer to the ATFL, which is formed by two fascicles (superior and inferior)(8,9), separated by a branch of the fibular artery(10):

- Superior fascicle of the ATFL: this fascicle is an intra-articular and extra-synovial structure. It is tense in plantar flexion and relaxed in dorsiflexion, and although it also controls anterior translation of the talus, its main function is to limit medial rotation of the talus. Due to its intra-articular and extra-synovial position, there are doubts about its healing capacity, and the current hypothesis is that after injury, the ligament stump may undergo a process of re-synovialization similar to that of the cruciate ligament in the knee(11). Therefore, its isolated injury is probably the cause of ankle micro-instability.

- Inferior fascicle of the ATFL: this fascicle is an extra-articular structure, connected inferiorly with the anterior portion of the CFL. It is an isometric fascicle, in the same way as the CFL, and for this reason the functional unit they form has been called the lateral tibiotalocalcaneal complex. Its main function is to limit anterior translation of the talus, and the connecting fibers to the CFL are robust enough to tension the latter, which would explain indirect repair of the CFL through the repair of the inferior fascicle of the ATFL(12).

On the other hand, it is known that chronic lateral instabilities can also affect the deltoid ligament, which also has an intra-articular fascicle, specifically the tibiotalar fascicle. For the same reasons as commented above, its healing capacity is expected to be poor(13).

These recent anatomical findings add to the evolving understanding of osteochondral injuries of the talus: during an inversion ankle sprain, impingement occurs between the medial part of the talar dome and the tibia. This impact can create a microscopic lesion in the joint cartilage, invisible on imaging tests, but which affects the biomechanics and has the potential to initiate a joint degeneration process(14,15).

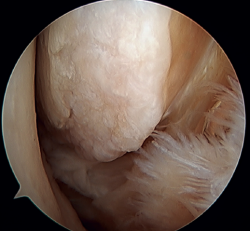

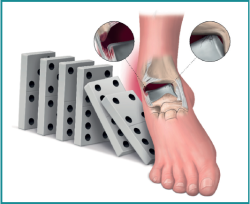

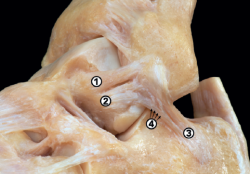

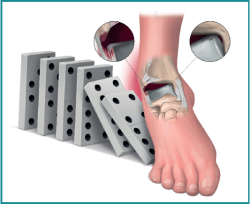

Therefore, the editorial "Ankle sprain and the domino effect" has recently been published, explaining how, following an inversion sprain, injury to the superior fascicle of the ATFL and talar cartilage, which initially may be asymptomatic, can alter the biomechanics of the ankle and cause injury to structures that were not initially affected(5) (Figure 2).

reacae.32284.fs2507015en-figure2.png

Figure 2. Ankle sprain and the domino effect: an inversion ankle sprain, even in mild cases, can cause injury to the superior fascicle of the anterior talofibular ligament and the cartilage of the talar dome. These injuries may be asymptomatic at first, but cause biomechanical alterations that can worsen the injuries or cause other lesions in areas of the ankle not initially affected. Image reproduced from the following open access publication: Dalmau-Pastor M, Calder J, Vega J, et al. The ankle sprain and the domino effect. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2024;32(12):3049-51.

Treatment of chronic lateral instability

There is some consensus that the surgical treatment of CLAI should be considered after 6 months of failure of rehabilitative treatment or when the patient has a long history of ankle instability or failure preventing him/her from performing daily activities or sports.

Routine arthroscopic evaluation is now recommended for the identification of intra-articular injuries prior to the procedure chosen to repair or reconstruct the damaged ligaments(6).

Traditionally, two main groups of surgical techniques have been described: "anatomical techniques", involving direct repair of the tissue in its native location or substitution with allo- or autografts in an anatomical position, i.e., using bone tunnels to reconstruct the distribution of the ligament in its correct location; and the so-called "non-anatomical techniques". Among the latter, several techniques have been described, such as tenodesis of the Achilles tendon or peroneal tendon(16), or allografts that mimic the function of the lateral ankle ligaments, such as the Chrisman-Snook procedure, the Watson-Jones procedure and the modified Evans procedure(17,18). In turn, among the anatomical techniques, a typical example is the Broström-Gould procedure(19), which augments repair with the extensor retinaculum.

Noailles(20), in a systematic review, reported a higher incidence of ankle osteoarthritis with non-anatomical techniques compared to direct repair. He moreover questioned the use of the peroneus brevis due to its important role in tibiotalar inversion stabilization. Vuurberg(21) also reported better functional results with anatomical techniques compared to non-anatomical techniques.

Consensus: There is now consensus that anatomical techniques offer better results in terms of functional outcomes, with a lesser risk of stiffness and progression to degenerative joint changes(20,21).

Arthroscopic or open treatment for chronic lateral instability

The last 15 years have seen the development of many arthroscopic techniques for the treatment of CLAI. The availability of specific implants and knotless systems has largely contributed to this.

Initially, the first systematic reviews yielded similar results in terms of assessment scales such as that of the American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS), the Karlsson scale, and the visual analogue scale (VAS), without finding statistically significant differences - although they pointed to less postoperative pain and a shorter average length of stay, as well as fewer soft tissue complications, in favor of the arthroscopic techniques(22).

Brown(23), in a meta-analysis, reported similar results with arthroscopic techniques in terms of the AOFAS and Karlsson scales. However, recent systematic reviews have evidenced a lower incidence of soft tissue and surgical wound complications(24,25). The most frequent complications in both techniques include neurological lesions, surgical wound or portal problems, deep vein thrombosis, or the recurrence of instability.

Zhi(25), in a systematic review and meta-analysis, concluded that arthroscopic repair affords excellent outcomes comparable to those of open surgery, but with better performance in terms of postoperative pain, and with a similar incidence of complications. In 2020, Moorthy(26) concluded that arthroscopic techniques have become the method of choice in the treatment of CLAI, and that they also allow the diagnosis and treatment of associated injuries. Attia(27) in turn found that although the arthroscopic technique is more technically demanding, the results obtained are superior on the AOFAS scale, VAS, and the time to full weight bearing. Woo(28) reported superior results with the arthroscopic technique on the VAS and AOFAS scale at 6 and 12 months postsurgery compared to the open technique.

In sum, the anatomical procedures for repair and reconstruction of the lateral complex yield similar clinical results, though probably with a lower incidence of complications, less postoperative pain and a shorter average hospital stay.

The second argument in favor of the arthroscopic techniques is the possibility to assess and treat associated injuries. The incidence of associated lesions varies between 70-100%(29,30,31). There is consensus on the combined and simultaneous surgical treatment of osteochondral lesions using any of the medullary stimulation techniques available to us(32).

Consensus: The current literature supports the arthroscopic treatment of chronic lateral ankle instability.

Indications of direct arthroscopic anterior talofibular ligament repair

Direct arthroscopic repair of the ATFL offers excellent results. Different techniques have been described, involving one or two implants, with or without knots and with or without augmentation. The many techniques described include those described by Conte-Real(33) and Acevedo(34), or the technique subsequently modified by Vega(35), performing an "all-inside" procedure with a knotless implant and a third accessory portal. The technique described by Conte-Real(33) is associated with a large number of neurological injuries to the sural nerve, since it involves percutaneous time for suture recovery and plication of the lateral retinaculum of the extensors. Vilá and Rico(36) in turn described the technique with two implants through a single portal in a cadaveric biomechanical study.

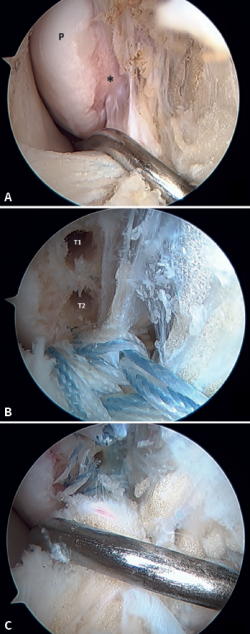

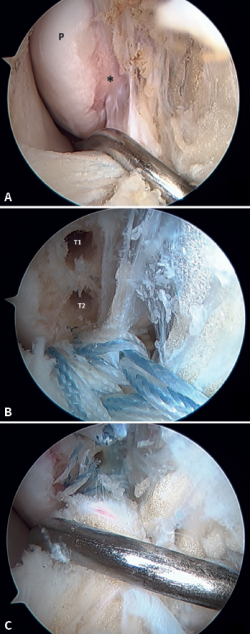

The main indication for this repair is rupture of the upper fascicle of the ATFL from its fibular insertion, with good tissue quality of the remaining ligament (Figure 3).

The technique can be performed through a single modified anterolateral portal or using a third accessory portal. The use of a single portal reduces the risk of injury to the intermediate dorsal cutaneous branch of the superficial peroneal nerve(37). Although there is no difference between the use of one or two implants, the use of two implants implies a larger contact surface(38,39) and improves patient incorporation to sports activities(40,41,42,43,44).

Another aspect to be considered is the angle of implant placement, due to possible complications related to drilling of the tunnels in the fibula. The best angle is between 30º and60°. An angle of30° is associated with an increased risk of peroneal tendon injuries, and an angle of60° increases the risk of fibular cortical fracture, with the recommended angle being about45°(43).

Vega(42) advocated the use of synthetic augmentation employing high-strength sutures, with the publishing of excellent results. Ulku(44) reported results comparable to the open Broström-Gould procedure with this technique, it being described as an arthroscopically safe procedure. In 2021, Lan(45) carried out a systematic review of the different augmentation techniques, concluding that the best results are obtained when previous repair of the ATFL remnant has been performed either by an open or arthroscopic procedure; he did not recommend the use of isolated augmentation, due to the poorer results obtained. In 2023, Mortada(38) published excellent results with this technique, using two implants and a single modified portal in a series of 100 patients, with statistically significant improvement on the AOFAS and Karlsson scales.

Consensus: The arthroscopic "all-inside" direct repair technique offers excellent results similar to those obtained with the open Broström-Gould procedure. A good quality tissue remnant is essential, however. Augmentation using synthetic sutures associated with the repair could allow earlier rehabilitation. There are no prospective randomized studies.

Indications of arthroscopic reconstruction

The techniques involving ATFL graft reconstruction via open surgery were described by Jeys(46) and Coughlin(47) in the early 2000s. Subsequently, and based on them, different arthroscopic techniques(48,49) have been described that restore joint stability with a low incidence of complications. These are the techniques of choice in cases of poor tissue quality, when ATFL rupture is at the talar insertion or in the mid-part of the ligament, in revision surgeries, and in patients with high functional demands, with hyperlaxity and/or a high body mass index (BMI).

These procedures are technically more demanding, although the development of biotenodesis-type implants and dynamic cortical anchorage systems has greatly facilitated their development and allows blind tunnels to be made, reducing neurovascular complications. Many different techniques and grafts have been described, each with potential advantages and disadvantages(24). Some studies on these techniques recommend resection of the ligament tissue remnant, as it poses a lesser risk of complications(50,51).

Brambilla(52), in a systematic review, sought to identify the best graft for lateral ankle reconstruction, though without finding studies of sufficient quality in the literature to endorse allo- or autografts. The conclusions of this meta-analysis show similar results in terms of stability, although allografting has the advantages of shortening the surgery time and fundamentally of avoiding morbidity at the donor site. Lu(53) and Li(54), in two meta-analyses including 12 and 6 papers, respectively, published in English, reported excellent results with arthroscopic reconstruction techniques, concluding that they are an excellent stabilization method, with few complications and no allograft-related problems.

However, there are few biomechanical studies comparing them. Clanton(55), in a study using semitendinosus grafts, found that maximum loading at failure was not significantly different from that of the intact ATFL. The average stiffness of the graft reconstruction was also not significantly different from that of the intact ATFL, concluding that anatomical reconstruction with graft has both strength and stiffness similar to that of the intact ligament in a time-zero cadaveric model. Along these same lines, Mellado(56,57) published a comparative biomechanical study in cadavers involving direct repair and reconstruction with grafting. Good results were obtained by both techniques, with only a significant difference in internal rotation in the axial plane in favor of reconstruction.

Body mass index is a debated topic. Many studies indicate that a high BMI is an indication for a reconstruction procedure, but there is no consensus on the BMI cut-off point in this respect. Jung(58) reported a cut-off point of > 25 kg/m2, while Dierckman(59) indicated a value of > 30 kg/m2.

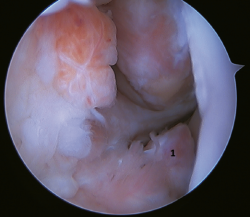

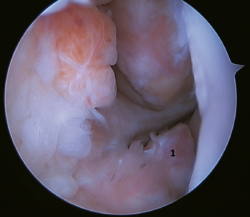

Another point of interest is the presence of os subfibulare. In these cases, we have the option of fixation, although this is usually not feasible and the best therapeutic option is excision and reconstruction, due to the impossibility of direct repair(60) (Figure 4).

Consensus: Reconstruction techniques offer good results in cases of major instability, poor tissue quality, high functional demands, and a high BMI.

Indications of calcaneofibular ligament reconstruction

The CFL is a powerful stabilizer of the ankle as well as of the subtalar joint. Approximately 30% of all ankle instabilities present coexisting subtalar joint instability(57,61).

Different surgical reconstruction techniques(62,63) involving 2 or 3 portals have been described.

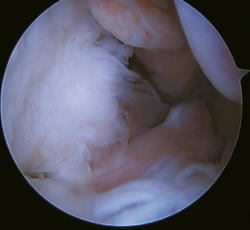

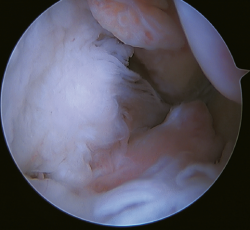

A recent consensus(64) recommends reconstruction of the ATFL and CFL (Figures 5 and 6) in cases of generalized laxity or when there is poor tissue quality. Other indications would be when there are doubts about subtalar stability or in patients with a ruptured CFL. For some authors, BMI > 30 kg/m2 would also be an indication for this technique.

In 2022, Ferkel(30) published the indications for reconstruction: failure of ligament repair, BMI > 30 kg/m2, cases of generalized laxity, athletes or workers with a high functional demand, and cases where poor tissue quality is observed intraoperatively. Another indication is when there is significant instability with a talar tilt angle difference of over 10° with respect to the contralateral ankle, or an absolute angle of more than15°. In the same paper, this author concluded that direct arthroscopic repair of the ATFL is an excellent technique in selected cases.

Lu(53), in his systematic review, found that 80% of athletes returned to their pre-injury level, concluding that allograft reconstruction procedures significantly improve function and the clinical scores, with a low incidence of complications and of recurrent instability.

Hunt(65), in a biomechanical work, attributed great importance to the CFL as a stabilizer in tibiotalar and subtalar inversion. In turn, Abarquero(66), in a cadaveric biomechanical study, found that dual plasty reconstruction (ATFL and CFL) provides greater angular stability of the tibiotalar joint compared to isolated ATFL reconstruction in a time-zero cadaveric ankle model.

Consensus: ATFL and CFL reconstruction offers excellent results and is indicated in cases where there are doubts about subtalar stability and in patients with marked instability.

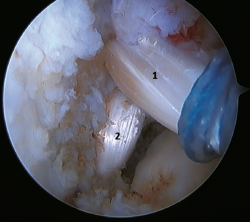

Arthroscopic treatment of rotational/multidirectional instability

Rotational instability is a relatively novel concept introduced in 2011 by Buchhorn(67), describing combined injuries of the lateral complex and deltoid ligament, and an anatomical reconstruction technique for both injuries. Although there is no biomechanical evidence as to why medial injury occurs in patients who have not suffered eversion trauma, it is likely that the stress maintained on the medial complex in lateral instability may evolve into rotational instability - which is in line with the previously commented domino effect theory (5,62). It is estimated that up to 10-15% of all cases of CLAI may progress to injury of the medial complex, especially affecting its most anterior fibers. Recently, Vega(68) described the combination of injuries of the lateral complex with the "book-page" injury (Figure 7) of the superficial tibiotalar fascicle of the deltoid ligament, due to excessive internal rotation in chronic lateral instability, and its treatment through direct repair of both lesions. Acevedo(34) and Vega(68) also described the safety position of the anchors in the medial malleolus.

The potential risks of arthroscopic repair of the medial complex include iatrogenic nerve injury, fracture of the medial malleolus, persistent medial instability, or medial gutter pain. The procedure is not technically complex, but requires experience in arthroscopic ankle techniques(69).

De Cesar(70) described the concept of multidirectional instability and distinguished combined instabilities, where CLAI can coexist with medial instability, CLAI with syndesmosis instability (often in the context of varus axial deviation) or medial instability with syndesmosis instability (often in the context of valgus axial deviation) versus multidirectional instabilities, characterized by the coexistence of CLAI, medial instability and chronic instability of the syndesmosis with or without subtalar instability.

The unresolved question in the literature is whether direct repair rather than reconstruction would be the best option in these cases of long-standing instability. Considering the studies reviewed in the present update, reconstruction of the ATFL and CFL is likely to be more effective.

Consensus: There are currently no systematic reviews or meta-analyses on the best treatment for rotational instabilities or the role of arthroscopy. Further prospective comparative studies are needed to increase the level of evidence on the arthroscopic and repair or reconstruction techniques.

Postoperative period and return to sports activities

These two aspects should be individualized, although the current trend is to be more aggressive in the postoperative period, allowing early mobility and isometric exercises to be performed 48 hours after surgery(71), with the use of a walking boot for 2-4 weeks, allowing progressive weight bearing(72). Dorsiflexion deficit is usually poorly tolerated by patients.

Li(73) performed a meta-analysis including 25 studies with 1,384 patients in which he found the time to return to sports activities to be 12.45 weeks (10.8-14.1 weeks). Vilá(4), in a recent study, reported a return to sports activities in about 6 months, with improvement of the Karlsson Ankle Functional Score (KAFS), on using a bifascicular reconstruction technique.

Lastly, a key issue in CLAI is the risk of developing ankle osteoarthritis. Recent studies have examined the relationship between CLAI and joint degeneration, suggesting that the early repair of ligament injuries may reduce the progression of post-traumatic osteoarthritis(74).

Conclusions

The current literature supports the arthroscopic treatment of chronic lateral ankle instability.

The arthroscopic "all-inside" direct repair technique offers excellent results similar to those of the open Broström-Gould procedure. A good quality tissue remnant is essential, however.

Reconstruction techniques offer good results in cases of major instability, poor tissue quality, high functional demands, and a high BMI.

The CFL plays an important role in tibiotalar and subtalar instability.

Figuras

Figure 1. Anatomical dissection showing the lateral fibulotalocalcaneal complex of the ankle. 1: superior fascicle of the anterior talofibular ligament; 2: inferior fascicle of the anterior talofibular ligament; 3: calcaneofibular ligament; 4: connecting fibers between the inferior fascicle of the anterior talofibular ligament and the calcaneofibular ligament. Image reproduced with permission: Hong CC, Lee JC, Tsuchida A, et al. Individual fascicles of the ankle lateral ligaments and the lateral fibulotalocalcaneal ligament complex can be identified on 3D volumetric MRI. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31(6):2192-8.

Figure 2. Ankle sprain and the domino effect: an inversion ankle sprain, even in mild cases, can cause injury to the superior fascicle of the anterior talofibular ligament and the cartilage of the talar dome. These injuries may be asymptomatic at first, but cause biomechanical alterations that can worsen the injuries or cause other lesions in areas of the ankle not initially affected. Image reproduced from the following open access publication: Dalmau-Pastor M, Calder J, Vega J, et al. The ankle sprain and the domino effect. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2024;32(12):3049-51.

Figure 3. A: identification of the fibular insertion of the ATFL (*) with excellent quality of the tissue remnant; B: technique with two knotless implants and using a modified single anterolateral portal; C: final result. P: fibula; T1: talofibular tunnel; T2: calcaneofibular tunnel.

Figure 5. Tearing of the anterior talofibular ligament and calcaneofibular ligament with poor tissue quality of the ligament remnant.

Figure 6. Arthroscopic view of a dual allograft reconstruction of the anterior talofibular ligament (1) and the calcaneofibular ligament (2), showing correct tension and positioning of the fascicles.

Información del artículo

Cita bibliográfica

Autores

Jesús Vilá y Rico

Servicio de Cirugía Ortopédica y Traumatología. Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre. Madrid

Departamento de Cirugía. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Madrid

Complejo Hospitalario Quirón Ruber. Madrid

Presidente saliente de la Revista del Pie y Tobillo

José María García López

Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology Service. Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre. Madrid

María Ángela Mellado Romero

Servicio de Cirugía Ortopédica y Traumatología. Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre. Madrid

Miquel Dalmau Pastor

Unidad de Anatomía Humana. Departamento de Patología y Terapéutica Experimental. Facultad de Medicina. Universidad de Barcelona

GRECMIP-MIFAS (Groupe de Recherche et d’Etude en Chirurgie Mini-Invasive du Pied Minimally Invasive Foot and Ankle Society). Merignac, Francia

Ethical responsibilities

Conflicts of interest. The author Jesús Vilá y Rico declares the following conflict of interest: international consultant for Arthrex.

Financial support. This study has received no financial support.

Protection of people and animals. The authors declare that this research has not involved human or animal experimentation.

Data confidentiality. The authors declare that the protocols of their work center referred to the publication of patient information have been followed.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Referencias bibliográficas

-

1Herzog MM, Kerr ZY, Marshall SW, Wikstrom EA. Epidemiology of Ankle Sprains and Chronic Ankle Instability. J Athl Train. 2019;54(6):603-10.

-

2Peters JW, Trevino SG, Renstrom PA. Chronic Lateral Ankle Instability. Foot Ankle. 1991;12(3):182-91.

-

3Webster KA, Gribble PA. Functional Rehabilitation Interventions for Chronic Ankle Instability: A Systematic Review. J Sport Rehabil. 2010;19(1):98-114.

-

4Vilá-Rico J, Mortada-Mahmoud A, Fernández-Rojas E, et al. Arthroscopic reconstruction of the anterior talofibular ligament and calcaneofibular ligament using allograft for chronic lateral ankle instability allows patients to successfully return to their pre-injury sports activities with Excellent clinical outcome at minimum two year follow-up. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2025;S0749806325000556.

-

5Dalmau-Pastor M, Calder J, Vega J, et al. The ankle sprain and the domino effect. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2024;32(12):3049-51.

-

6Hertel J. Functional Anatomy, Pathomechanics, and Pathophysiology of Lateral Ankle Instability. J Athl Train. 2002;37(4):364-75.

-

7Dalmau-Pastor M, Malagelada F, Calder J, et al. The lateral ankle ligaments are interconnected: the medial connecting fibres between the anterior talofibular, calcaneofibular and posterior talofibular ligaments. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(1):34-9.

-

8Dalmau-Pastor M, El-Daou H, Stephen JM, et al. Clinical Relevance and Function of Anterior Talofibular Ligament Superior and Inferior Fascicles: A Robotic Study. Am J Sports Med. 2023;51(8):2169-75.

-

9Dalmau-Pastor M, Malagelada F, Kerkhoffs GM, et al. Redefining anterior ankle arthroscopic anatomy: medial and lateral ankle collateral ligaments are visible through dorsiflexion and non-distraction anterior ankle arthroscopy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(1):18-23.

-

10Vega J, Malagelada F, Manzanares Céspedes MC, Dalmau-Pastor M. The lateral fibulotalocalcaneal ligament complex: an ankle stabilizing isometric structure. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(1):8-17.

-

11Murray MM, Martin SD, Martin TL, Spector M. Histological Changes in the Human Anterior Cruciate Ligament After Rupture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(10):1387-97.

-

12Cordier G, Nunes GA, Vega J, et al. Connecting fibers between ATFL’s inferior fascicle and CFL transmit tension between both ligaments. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29(8):2511-6.

-

13Dalmau-Pastor M, Malagelada F, Guelfi M, et al. The deltoid ligament is constantly formed by four fascicles reaching the navicular, spring ligament complex, calcaneus and talus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2024;32(12):3065-75.

-

14Blom RP, Mol D, van Ruijven LJ, et al. A Single Axial Impact Load Causes Articular Damage That Is Not Visible with Micro-Computed Tomography: An Ex Vivo Study on Caprine Tibiotalar Joints. Cartilage. 2021;13(2_suppl):1490S-1500S.

-

15Dahmen J, Karlsson J, Stufkens SAS, Kerkhoffs GMMJ. The ankle cartilage cascade: incremental cartilage damage in the ankle joint. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29(11):3503-7.

-

16Gerstner Garces JB. Chronic ankle instability. Foot Ankle Clin. 2012;17(3):389-98.

-

17Chrisman OD, Snook GA. Reconstruction of lateral ligament tears of the ankle. An experimental study and clinical evaluation of seven patients treated by a new modification of the Elmslie procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51(5):904-12.

-

18Evans DL. Recurrent instability of the ankle; a method of surgical treatment. Proc R Soc Med. 1953;46(5):343-4.

-

19Gould N, Seligson D, Gassman J. Early and Late Repair of Lateral Ligament of the Ankle. Foot Ankle. 1980;1(2):84-9.

-

20Noailles T, Padiolleau G, Gouin F, Brilhault J. Non-anatomical or direct anatomical repair of chronic lateral instability of the ankle: A systematic review. Foot Ankle Surg. 2018;24:80-5.

-

21Vuurberg G, Pereira H, Blankevoort L, Van Dijk CN. Anatomic stabilization techniques provide superior results in terms of functional outcome in patients suffering from chronic ankle instability compared to non-anatomic techniques. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(7):2183-95.

-

22Rigby RB, Cottom JM. A comparison of the “All-Inside” arthroscopic Broström procedure with the traditional open modified Broström-Gould technique: A review of 62 patients. Foot Ankle Surg. 2019;25(1):31-6.

-

23Brown AJ, Shimozono Y, Hurley ET, Kennedy JG. Arthroscopic versus open repair of lateral ankle ligament for chronic lateral ankle instability: a meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(5):1611-8.

-

24Yasui Y, Murawski CD, Wollstein A, et al. Operative Treatment of Lateral Ankle Instability. JBJS Rev. 2016;4(5):e6.

-

25Zhi X, Lv Z, Zhang C, et al. Does arthroscopic repair show superiority over open repair of lateral ankle ligament for chronic lateral ankle instability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg. 2020;15(1):355.

-

26Moorthy V, Sayampanathan AA, Yeo NEM, Tay KS. Clinical Outcomes of Open Versus Arthroscopic Broström Procedure for Lateral Ankle Instability: A Meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2021;60(3):577-84.

-

27Attia AK, Taha T, Mahmoud K, et al. Outcomes of Open Versus Arthroscopic Broström Surgery for Chronic Lateral Ankle Instability: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Comparative Studies. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021;9(7):23259671211015207.

-

28Woo BJ, Lai MC, Koo K. Arthroscopic Versus Open Broström-Gould Repair for Chronic Ankle Instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2020;41(6):647-53.

-

29Lee J, Hamilton G, Ford L. Associated intra-articular ankle pathologies in patients with chronic lateral ankle instability: arthroscopic findings at the time of lateral ankle reconstruction. Foot Ankle Spec. 2011;4(5):284-9.

-

30Ferkel RD, Chams RN. Chronic Lateral Instability: Arthroscopic Findings and Long-Term Results. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28(1):24-31.

-

31Arroyo-Hernández M, Mellado-Romero M, Páramo-Díaz P, et al. Chronic ankle instability: Arthroscopic anatomical repair. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2017;61(2):104-10.

-

32Zengerink M, Struijs PAA, Tol JL, Van Dijk CN. Treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(2):238-46.

-

33Corte-Real NM, Moreira RM. Arthroscopic repair of chronic lateral ankle instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30(3):213-7.

-

34Acevedo JI, Mangone P. Arthroscopic Broström technique. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36(4):465-73.

-

35Vega J, Golanó P, Pellegrino A, Rabat E, Peña F. All-inside arthroscopic lateral collateral ligament repair for ankle instability with a knotless suture anchor technique. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34(12):1701-9.

-

36Vilá y Rico J, Mellado Romero M.A, Guerra Pinto F, et al. Estudio biomecánico de la reparación ligamentosa anatómica en la inestabilidad lateral de tobillo. Rev Esp Artrosc Cir Articul. 2020;27(4):291-8.

-

37Zhou YF, Zhang HZ, Zhang ZZ, et al. Comparison of Function- and Activity-Related Outcomes After Anterior Talofibular Ligament Repair With 1 Versus 2 Suture Anchors. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021;9(7):2325967121991930.

-

38Liu C, Zhang Z, Wang J, et al. Optimal fibular tunnel direction for anterior talofibular ligament reconstruction: 45 degrees outperforms 30 and 60 degrees. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31(10):4546-50.

-

39Mortada-Mahmoud A, Fernández-Rojas E, Iglesias-Durán E, et al. Results of Anatomical Arthroscopic Repair of Anterior Talofibular Ligament in Chronic Lateral Ankle Instability Patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2023;44(12):1219-28.

-

40Feng SM, Wang AG, Sun QQ, Zhang ZY. Functional Results of All-Inside Arthroscopic Broström-Gould Surgery With 2 Anchors Versus Single Anchor. Foot Ankle Int. 2020;41(6):721-7.

-

41Li H, Hua Y, Li H, Chen S. Anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) repair using two suture anchors produced better functional outcomes than using one suture anchor for the treatment of chronic lateral ankle instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(1):221-6.

-

42Vega J, Montesinos E, Malagelada F, et al. Arthroscopic all-inside anterior talo-fibular ligament repair with suture augmentation gives excellent results in case of poor ligament tissue remnant quality. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(1):100-7.

-

43Michels F, Matricali G, Guillo S, et al. An oblique fibular tunnel is recommended when reconstructing the ATFL and CFL. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(1):124-31.

-

44Ulku TK, Kocaoglu B, Tok O, et al. Arthroscopic suture-tape internal bracing is safe as arthroscopic modified Broström repair in the treatment of chronic ankle instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(1):227-32.

-

45Lan R, Piatt ET, Bolia IK, et al. Suture Tape Augmentation in Lateral Ankle Ligament Surgery: Current Concepts Review. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2021;6(4):24730114211045978.

-

46Jeys LM, Harris NJ. Ankle stabilization with hamstring autograft: a new technique using interference screws. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24(9):677-9.

-

47Coughlin MJ, Schenck RC, Grebing BR, Treme G. Comprehensive Reconstruction of the Lateral Ankle for Chronic Instability Using a Free Gracilis Graft. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25(4):231-41.

-

48Vilá-Rico J, Cabestany-Castellà JM, Cabestany-Perich B, et al. All-inside arthroscopic allograft reconstruction of the anterior talo-fibular ligament using an accessory transfibular portal. Foot Ankle Surg. 2019;25(1):24-30.

-

49Allegra F, Boustany SE, Cerza F, et al. Arthroscopic anterior talofibular ligament reconstruction in chronic ankle instability: Two years results. Injury. 2020;51:S56-62.

-

50Wang Z, Zheng G, Chen W, et al. Double-bundle reconstruction of the anterior talofibular ligament by partial peroneal brevis tendon. Foot Ankle Surg. 2023;29(3):249-55.

-

51Wittig U, Hohenberger G, Ornig M, et al. All-arthroscopic reconstruction of the anterior talofibular ligament is comparable to open reconstruction: a systematic review. EFORT Open Rev. 2022;7(1):3-12.

-

52Brambilla L, Bianchi A, Malerba F, et al. Lateral ankle ligament anatomic reconstruction for chronic ankle instability: Allograft or autograft? A systematic review. Foot Ankle Surg. 2020;26(1):85-93.

-

53Lu A, Wang X, Huang D, et al. The effectiveness of lateral ankle ligament reconstruction when treating chronic ankle instability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury. 2020;51(8):1726-32.

-

54Li H, Song Y, Li H, Hua Y. Outcomes After Anatomic Lateral Ankle Ligament Reconstruction Using Allograft Tendon for Chronic Ankle Instability: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2020;59(1):117-24.

-

55Clanton TO, Viens NA, Campbell KJ, et al. Anterior talofibular ligament ruptures, part 2: biomechanical comparison of anterior talofibular ligament reconstruction using semitendinosus allografts with the intact ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):412-6.

-

56Mellado-Romero MÁ, Guerra-Pinto F, Guimarães-Consciência J, et al. Estudio biomecánico de la reconstrucción ligamentosa anatómica con autoinjerto en la inestabilidad lateral de tobillo. Rev Esp Cir Ortopédica Traumatol. 2021;65(2):124-31.

-

57Mellado-Romero MÁ, Guerra-Pinto F, Ojeda-Thies C, et al. Comparison of Direct Repair Versus Anatomic Graft Reconstruction of the Anterior Talofibular Ligament: A Biomechanical Cadaveric Study. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2024;63(1):36-41.

-

58Jung HG, Shin MH, Park JT, et al. Anatomical Reconstruction of Lateral Ankle Ligaments Using Free Tendon Allografts and Biotenodesis Screws. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36(9):1064-71.

-

59Dierckman BD, Ferkel RD. Anatomic Reconstruction With a Semitendinosus Allograft for Chronic Lateral Ankle Instability. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(8):1941-50.

-

60Li HY, Xuan WK, Tao HY, et al. Satisfactory outcomes from the double-row fixation procedure for ankle lateral ligaments injury with os subfibulare. Asia-Pac J Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Technol. 2024;35:32-8.

-

61Iglesias-Durán E, Guerra-Pinto F, Ojeda-Thies C, Vilá-Rico J. Reconstruction of the interosseous talocalcaneal ligament using allograft for subtalar joint stabilization is effective. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31(12):6080-7.

-

62Michels F, Pereira H, Calder J, et al. Searching for consensus in the approach to patients with chronic lateral ankle instability: ask the expert. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(7):2095-102.

-

63Vilá-Rico J, Fernández-Rojas E, Jiménez-Blázquez JL, et al. Arthroscopic Anatomic Reconstruction of the Anterior Talofibular and Calcaneofibular Ligaments Through a 2-Portal Technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2024;13(4):102914.

-

64Campillo Recio D, Calle García JA, Albertí Fito G, Vilá y Rico J. Ligamentoplastia artroscópica para la inestabilidad lateral de tobillo. Rev Esp Artrosc Cir Articul. 2024;31(2):123-31.

-

65Hunt KJ, Pereira H, Kelley J, et al. The Role of Calcaneofibular Ligament Injury in Ankle Instability: Implications for Surgical Management. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(2):431-7.

-

66Abarquero-Diezhandino A, Mellado-Romero MÁ, Muñoz de la Espada-López M, et al. Estudio biomecánico en cadáver de reconstrucción con plastia de los ligamentos peroneoastragalino anterior y peroneocalcáneo. Rev Esp Cir Ortopédica Traumatol. 2024;68(6).

-

67Buchhorn T, Sabeti-Aschraf M, Dlaska CE, et al. Combined medial and lateral anatomic ligament reconstruction for chronic rotational instability of the ankle. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32(12):1122-6.

-

68Vega J, Allmendinger J, Malagelada F, et al. Combined arthroscopic all-inside repair of lateral and medial ankle ligaments is an effective treatment for rotational ankle instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(1):132-40.

-

69Li CCH, Lui TH. Arthroscopic Deltoid Ligament Reconstruction in Rotational Ankle Instability. Arthrosc Tech. 2023;12(7):e1179-84.

-

70De Cesar Netto C, Valderrabano V, Mansur NSB. Multidirectional Chronic Ankle Instability. Foot Ankle Clin. 2023;28(2):405-26.

-

71Gottlieb U, Hayek R, Hoffman JR, Springer S. Exercise combined with electrical stimulation for the treatment of chronic ankle instability – A randomized controlled trial. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2024;74:102856.

-

72Guo Y, Cheng T, Yang Z, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of balance training in patients with chronic ankle instability. Syst Rev. 2024;13(1):64.

-

73Li Y, Su T, Hu Y, et al. Return to Sport After Anatomic Lateral Ankle Stabilization Surgery for Chronic Ankle Instability: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2024;52(2):555-66.

-

74Herrera-Pérez M, Valderrabano V, Godoy-Santos AL, et al. Ankle osteoarthritis: comprehensive review and treatment algorithm proposal. EFORT Open Rev. 2022;7(7):448-59.

Descargar artículo:

Licencia:

Este contenido es de acceso abierto (Open-Access) y se ha distribuido bajo los términos de la licencia Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND (Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional) que permite usar, distribuir y reproducir en cualquier medio siempre que se citen a los autores y no se utilice para fines comerciales ni para hacer obras derivadas.

Comparte este contenido

En esta edición

- Anterior ankle arthroscopy at its best

- Foot and ankle arthroscopy, a consolidated and expanding reality

- The history and current concepts of ankle arthroscopy

- Current status of anterior ankle impingement

- Arthroscopic treatment of chronic lateral ankle instability

- Managing osteochondral lesions of the talus with anterior ankle arthroscopy

- Role of arthroscopy in syndesmosis injuries

- Role of arthroscopy in the treatment of ankle fractures

- Anterior arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis

- The use of needle arthroscopy in the ankle

- The letter pi on the ankle

Más en PUBMED

Más en Google Scholar

Más en ORCID

Revista Española de Artroscopia y Cirugía Articular está distribuida bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional.