Managing osteochondral lesions of the talus with anterior ankle arthroscopy

Tratamiento de las lesiones osteocondrales del astrágalo mediante artroscopia anterior del tobillo

Resumen:

Las lesiones osteocondrales del astrágalo (osteochondral lesions of the talus –OLT–) se asocian con frecuencia a traumatismos del tobillo y pueden provocar síntomas y discapacidad importantes. Los pacientes suelen presentar dolor profundo en el tobillo entre 6 y 12 meses después de la lesión inicial. Las OLT pueden visualizarse mediante técnicas de imagen como la tomografía computarizada (TC) y la resonancia magnética (RM). Existe un acuerdo general acerca de que el tratamiento no quirúrgico debe ser el tratamiento inicial. Si el tratamiento no quirúrgico no conduce a una mejoría clínica suficiente, existen diversas opciones de tratamiento quirúrgico, tanto mediante artroscopia como mediante técnicas abiertas. La elección del tratamiento depende de las características tanto del paciente como de la lesión. Dada su naturaleza menos invasiva y sus tiempos de recuperación más cortos, las técnicas artroscópicas suelen considerarse como primera opción quirúrgica. Este artículo describe la etiología y el diagnóstico de las OLT y resume las opciones de tratamiento artroscópico disponibles más utilizadas, como la estimulación de la médula ósea, la perforación retrógrada, la fijación y las técnicas de implantación de cartílago.

Abstract:

Osteochondral lesions of the talus (OLT) are commonly associated with ankle trauma and can lead to significant symptoms and disability. Patients typically present with deep ankle pain 6-12 months following the initial injury. OLTs can be visualized through imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT) scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). There is general agreement that non-surgical treatment should be the initial treatment. If non-surgical management does not lead to sufficient clinical improvement, various surgical treatment options are available, both through arthroscopy as well as open techniques. The choice of treatment depends on both patient and lesion characteristics. Given their less invasive nature and shorter recovery times, arthroscopic techniques may usually be considered as a first surgical option. This article describes the etiology and diagnosis of OLTs and summarizes the available evidence on the most commonly used arthroscopic treatment options, such as bone marrow stimulation (BMS), retrograde drilling, fixation and cartilage implantation techniques.

Introduction

An osteochondral lesion of the talus (OLT) is defined as damage to the subtalar bone and overlying articular cartilage. These lesions typically develop after trauma to the ankle(1,2,3). OLTs have been shown to occur in over 65% of chronic ankle sprains, and up to 75% of ankle fractures(2,3). The etiology of OLT is currently unknown. However, it is hypothesized that during trauma, the talus impacts the tibial plateau, creating microcracks in the cartilage and subchondral bone plate(1,4,5,6). It is theorized that during weightbearing, an increased pressure in the joint can lead to infiltration of synovial fluid through these microfractures, leading to inducing osteonecrosis and therefore leading to lesion expansion and the formation of an OLT(4).

Patients typically present 6-12 months after ankle trauma with deep ankle pain, provoked during or after weightbearing activities. Other presenting symptoms may include a locking or clicking sensation, swelling or stiffness of the ankle(4,7). Thorough physical examination and anamnesis are essential for adequate diagnosis and treatment decision-making. Forced palpation of the talar dome during plantar flexion may provoke the recognizable deep ankle pain sensation, if the lesion is located anteriorly enough to be able to palpate(4,7).

Further imaging can be deployed when there is a clinical suspicion for an OLT. Radiographs can be useful for assessing the ankle alignment but have a low diagnostic value in OLTs(8). Radiological confirmation and evaluation of OLTs should be conducted using computed tomography (CT) scans and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which have high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity(8,9). MRI can be useful to assess the ankle cartilage, detect bone marrow edema, or diagnose concomitant soft tissue injuries of the ankle. However, CT is preferred to assess the bony morphology and size of OLTs and to assess the subchondral bone layer, because MRI can overestimate lesion size due to the bone edema(9,10). Additionally, CT is a valuable tool for the assessment of the subchondral bone layer, which plays a significant role for OLTs(7). CT is also useful in pre-operative planning, for instance the feasibility of reaching the OLT arthroscopically(11). Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) combines CT-based assessment of lesion size and morphology with functional imaging of lesion activity(12,13). Thus, SPECT may be of added value in treatment decision-making in complex cases with co-existing pathology, to identify the main cause of symptoms when standard imaging and clinical evaluation fail to provide adequate diagnostic insight(9).

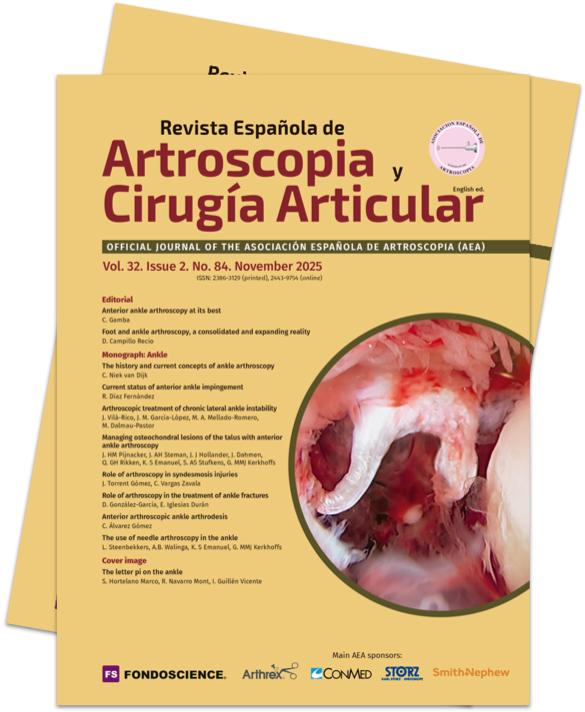

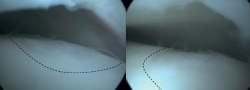

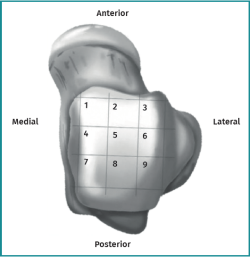

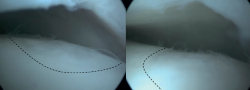

Lesions can be characterized by location, morphology, and size. Location can be described using a 9-grid anatomical scheme of the talus, as described by Raikin et al., shown in Figure 1(14). The morphology of OLTs can be described as crater-like, cystic, or fragmentary (Figure 2)(4,15,16). Lesion size should be reported in anterior-posterior plane, medial-lateral plane, and depth, allowing for calculation of lesion surface area and volume(4). However, there is no consensus on the reporting on morphology of OLTs, and while radiological classification systems for OLTs exist, they lack validation and utilize inconsistent terminology. Moreover, lesion size measurement methods vary, further contributing to inconsistency in lesion characterization in literature(15).

Treatment of OLT should start with an initial period of 3-6 months of non-operative treatment, unless fixation of an acute displaced fragment (i.e., acute intra-articular osteochondral fracture) is feasible(17). The non-operative treatment may include physiotherapy focusing on range of motion, strength, balance and proprioception, or treatments such as cast immobilization, orthopedic insoles shoe adjustments, weight loss, psychological treatment, occupational modifications and injections of hyaluronic acid or corticosteroids(4). Non-operative treatment is successful in about 45% of patients(18).

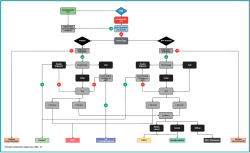

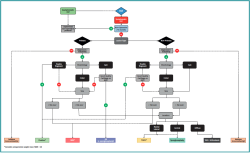

If patients remain symptomatic after the non-operative treatment period, surgical intervention can be considered. Appropriate surgical treatment should be decided using shared decision-making and a personalized approach, incorporating patient characteristics (such as age, body mass index [BMI], preoperative level of activities, and patient preference), lesion factors (primary or non-primary [non-primary meaning failed previous surgical treatment of the OLT], lesion size (area and volume), and morphology) and concomitant foot and ankle pathology (e.g., hindfoot alignment, ankle stability, and concomitant injuries)(4). These factors are incorporated in a multi-level algorithm-based treatment paradigm. Different paradigms exist(4,19), one of which can be appreciated in Figure 3.

Arthroscopic surgical techniques can be an appropriate option to treat small (<15 mm), primary osteochondral lesions of the talus, though arthroscopic procedures can be successful for non-primary lesions as well(20,21). Arthroscopic techniques have smaller skin incisions, do not require an osteotomy, and therefore typically have shorter recovery time compared to open surgical techniques for osteochondral lesions of the talus. Given their less invasive nature, arthroscopic techniques may usually be considered as a first surgical option. However, when arthroscopic surgical techniques are not feasible, for instance for larger lesions (>15 mm), previous failed arthroscopic surgery and a repeat procedure is not suitable, or when the lesion is difficult to access through arthroscopic portals, open surgical techniques can be considered(4). The following section will discuss different types of arthroscopic surgical techniques for the treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus.

Surgical techniques

Bone marrow stimulation

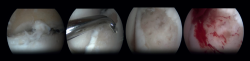

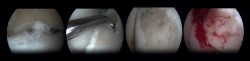

Arthroscopic Bone Marrow Stimulation (BMS) is the most frequently used treatment for primary OLT(22). BMS can be deployed for relatively smaller (<15 mm), non-cystic, non-fixable lesions(20,23). Arthroscopic BMS starts with debridement and curettage of the defective cartilage and subchondral bone(24). Subsequently, drilling or perforation of the sclerotic bone at the base of the defect is performed, often using a Kirschner wire or microfracture awl(25). The holes should be made to a depth that results in bleeding of the subchondral bone or the presence of fat droplets(23) (Figure 4). This technique disrupts the intraosseous blood vessels, leading to the subchondral bone bleeding and the formation of a fibrin clot. The release of mesenchymal blood cells promotes vascularization which induces the formation of fibrocartilage(26). When an isolated (i.e., no other damage to bone/within the joint) cartilage lesion with a macroscopically intact subchondral bone layer, is present, debridement only can be performed(27).

The success rate for BMS for primary lesions is reported to be 82%, with a complication rate of 4% and a reoperation rate of 7%(22,28,29). The reported success rate for secondary lesions is lower, at 69-75%(21). The progression of osteoarthritis after BMS has been a concern, due to the faster deterioration of fibrocartilage as opposed to hyaline cartilage. Although only 18 % of patients underwent revision surgery at 10-year follow up(30), after a mean follow-up of 13-years, progression of osteoarthritis was seen in 28 % of patients after BMS(31). Therefore, a variety of adjunct therapies have been described, aiming to improve the cartilage quality and subchondral bone repair. These adjunct therapies can be autologous blood products such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP) or bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC), that are administered at the end of the BMS-procedure(17,32,33). However, there is insufficient evidence to support a positive effect of these adjuncts, and the anticipated positive effects of these additional therapies have yet to be proven(34).

For the post-operative protocol after BMS, research shows that early weight-bearing provides similar or improved results after BMS compared to delayed weight-bearing(35,36). Therefore, early weightbearing after arthroscopic BMS is advised, which includes bandaging and crutches for the first two days post-operatively, whereafter increasing weight-bearing and reducing crutches in two weeks, as tolerated is recommended(24).

Retrograde drilling

Retrograde drilling is a non-transarticular technique, using fluoroscopy for visualization of the talus, which allows for debridement and drilling of the subcartilaginous cyst. Retrograde drilling can be considered as a surgical intervention for cystic OLTs with an intact articulate cartilage layer(22). Retrograde drilling allows for the penetration of the necrotic sclerotic zone for bone marrow stimulation, without damaging the intact cartilage surface(37). Similar to BMS, retrograde drilling causes disruption of the intraosseous blood vessels and thereby promoting subarticular bone filling of the cyst. After exposing the talus using anteromedial and anterolateral portals, a Kirschner wire will be positioned under fluoroscopic control, transtalar from the opposite talar neck into the subchondral sclerotic zone(37).

As an additional procedure, the debrided cyst can be filled with cancellous bone, particularly for large lesions, since the insufficient stem cells in the subchondral bone in these cases lead to a lower likelihood of adequate regeneration of damaged cartilage and subchondral bone(22,38). For primary OLTs, retrograde drilling has a success rate between 68% and 100% and a complication rate of 5%(22,29).

The post-operative protocol after retrograde drilling typically consists of 6 weeks of partial weight-bearing, allowing full range of motion immediately. Full weight-bearing is allowed after 6 weeks.

Fixation techniques

Fixation techniques are primarily applied to osteochondral lesions of the talus (OLTs) with fragmentary morphology. Consensus was that, for these techniques to be technically feasible, the lesion fragment should have a diameter of at least 10 mm and a depth of 3 mm(39). However, successful fixation has also been described for smaller lesions in studies using cortical bone pegs(40).

For acute displaced fragmentary lesions, fixation should be considered as the initial treatment(4). This should be performed as soon as possible to maximize healing potential and avoid further intra-articular damage(39). For chronic lesions, fixation can be applied when non-operative management is unsuccessful. As fixation techniques can provide superior subchondral bone healing(41), as well as preserving the overlying hyaline cartilage, it should be considered as the primary surgical treatment option when feasible.

Several fixation techniques using different materials have been described, including Kirschner wires, metal screws, bio-absorbable screws, bone pegs and/or fibrin glue(42,43,44,45). Fixation techniques may be performed arthroscopically when technically possible. The less invasive nature of arthroscopic fixation is theoretically advantageous. The most decisive factor for the possibility of arthroscopic fixation being the location/accessibility of the lesion. To achieve an adequate and stable fixation, the fragment needs to be fixated perpendicular to the talar dome. Therefore, the lesion must be located relatively anterior on the talar dome for arthroscopic fixation to be feasible(11). If arthroscopic fixation is not technically possible, it can also be performed as an open technique.

One specific surgical fixation technique is the Lift, Drill, Fill and Fix (LDFF) procedure(45). In this technique, the osteochondral lesion is visualized, and a beaver knife is used to create a flap. The flap is then lifted to allow for debridement and microfracturing of the subchondral bone. Cancellous bone, typically harvested from the distal tibial metaphysis, can be placed in the bed of the flap. Finally, the osteochondral flap is repositioned and fixed using bio-absorbable compression screws, chondral darts or bone pegs.

Fixation techniques have shown clinical and radiological success in 8 out of 10 patients, also maintaining their success in the long term (Figures 5 and 6). As these techniques preserve the hyaline cartilage and provide superior healing of the subchondral bone, they are advantageous over other surgical treatment options for OLTs, when feasible(39,41).

Cartilage implantation

Cartilage implantation techniques, such as autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) and matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation (MACI), aim to regenerate the hyaline-like cartilage by implanting harvested and cultured chondrocytes in the osteochondral lesion(46,47,48). These techniques typically use a two-step technique. During the first step, chondrocytes are harvested from a non-weightbearing area of the talus or margins of the lesion during an arthroscopic procedure. Thereafter, these chondrocytes are cultured in-vitro. The second phase consists of reimplanting the cultured chondrocytes in the excised lesion.

For ACI, the cultivated chondrocytes are implanted in a second procedure that occurs typically 3 weeks after step 1(47). During this second procedure, a medial or lateral osteotomy is performed to gain access to the lesion, whereafter the lesion is debrided to prepare for implantation. After implantation, the implanted chondrocytes are then covered by a periosteal flap from the distal tibia(49). Fibrin glue is used to seal the junction of the flap with the articular cartilage(49).

For the MACI-technique, the chondrocytes are cultured and embedded in a biodegradable scaffold, to prevent morbidity of the periosteal flap and harvest-site(46,48). The second step is typically performed 8-12 weeks after harvesting the chondrocytes. Access is gained through medial or lateral osteotomy, and after debridement of the lesion, lesion size is measured using a foil template. The MACI graft is then cut around the template and is placed into the lesion with the side containing the cells facing the defect. Thereafter, fibrin glue is used to secure the graft(50).

These techniques have shown promising results in the knee, resulting in superior tissue regeneration compared to BMS(51). This has yet to be proven for osteochondral lesion of the talus. However, these techniques have some disadvantages; they require an additional surgical procedure, and the laboratory with the necessary resources to perform these techniques can be quite costly. Autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis (AMIC) is a new generation scaffold-based therapy that combines a collagen matrix scaffold with microfracture and does not require a two-step procedure(52). The AMIC membrane is a collagen type I/III bilayer matrix, that stabilizes the super clot that forms on top of the lesion after microfracturing. This prevents the loss of cells through leakage into the joint space and limits the mechanical stress on the regeneration zone. This supports the chondrogenic differentiation and enhances proteoglycan deposition, leading to the formation of hyaline cartilage. During the AMIC procedure, the osteochondral lesion is debrided, and subchondral bone is stimulated with bone marrow stimulation, whereafter the AMIC membrane is cut into the exact size of the defect before it is introduced and fixated with fibrin glue(52).

Cartilage implantation techniques have a reported success rate of 70-92%, and a complication rate of 5%(18,29). Post-operative management typically consists of non-weightbearing for 6 weeks. Full weight-bearing is typically allowed after 7-9 weeks(47,50).

Conclusion

This article provides an overview of the etiology and diagnosis of osteochondral lesions of the talus (OLT) and summarizes the current literature regarding arthroscopic treatment options. Non-operative management should be the initial approach for OLTs. If non-operative treatment fails, fixation techniques, such as such as the Lift, Drill, Fill, and Fix (LDFF) procedure, when technically feasible, may be considered as the initial surgical treatment option. In the absence of a fixable fragment, arthroscopic treatment with bone marrow stimulation or cartilage implantation techniques may be effective. If arthroscopic treatment fails, or is not technically feasible, open surgical techniques remain an alternative for treating OLTs.

Figuras

Figure 2. Types of morphologies of OLTs as seen on CT on coronal and sagittal view. A: crater-like; B: cystic; C: fragmentary.

Figure 3. Flowchart for surgical management of OLTs, modified version of the flowchart by Rikken et al.(4), with permission of the authors.

Información del artículo

Cita bibliográfica

Autores

Juliëtte HM Pijnacker

Departamento de Cirugía Ortopédica y Medicina Deportiva. Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC). Sede AMC. Universidad de Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Ciencias del Movimiento de Ámsterdam. Programas de Deporte y Salud Musculoesquelética. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Centro Académico de Medicina Deportiva Basada en la Evidencia (ACES). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Colaboración de Ámsterdam para la Salud y la Seguridad en el Deporte (ACHSS). Centro de Investigación del Comité Olímpico Internacional (COI). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Jason AH Steman

Departamento de Cirugía Ortopédica y Medicina Deportiva. Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC). Sede AMC. Universidad de Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Ciencias del Movimiento de Ámsterdam. Programas de Deporte y Salud Musculoesquelética. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Centro Académico de Medicina Deportiva Basada en la Evidencia (ACES). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Colaboración de Ámsterdam para la Salud y la Seguridad en el Deporte (ACHSS). Centro de Investigación del Comité Olímpico Internacional (COI). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Julian J Hollander

Departamento de Cirugía Ortopédica y Medicina Deportiva. Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC). Sede AMC. Universidad de Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Ciencias del Movimiento de Ámsterdam. Programas de Deporte y Salud Musculoesquelética. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Centro Académico de Medicina Deportiva Basada en la Evidencia (ACES). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Colaboración de Ámsterdam para la Salud y la Seguridad en el Deporte (ACHSS). Centro de Investigación del Comité Olímpico Internacional (COI). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Jari Dahmen

Departamento de Cirugía Ortopédica y Medicina Deportiva. Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC). Sede AMC. Universidad de Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Ciencias del Movimiento de Ámsterdam. Programas de Deporte y Salud Musculoesquelética. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Centro Académico de Medicina Deportiva Basada en la Evidencia (ACES). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Colaboración de Ámsterdam para la Salud y la Seguridad en el Deporte (ACHSS). Centro de Investigación del Comité Olímpico Internacional (COI). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Quinten GH Rikken

Departamento de Cirugía Ortopédica y Medicina Deportiva. Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC). Sede AMC. Universidad de Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Ciencias del Movimiento de Ámsterdam. Programas de Deporte y Salud Musculoesquelética. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Centro Académico de Medicina Deportiva Basada en la Evidencia (ACES). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Colaboración de Ámsterdam para la Salud y la Seguridad en el Deporte (ACHSS). Centro de Investigación del Comité Olímpico Internacional (COI). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Kaj S Emanuel

Departamento de Cirugía Ortopédica y Medicina Deportiva. Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC). Sede AMC. Universidad de Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Ciencias del Movimiento de Ámsterdam. Programas de Deporte y Salud Musculoesquelética. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Centro Académico de Medicina Deportiva Basada en la Evidencia (ACES). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Colaboración de Ámsterdam para la Salud y la Seguridad en el Deporte (ACHSS). Centro de Investigación del Comité Olímpico Internacional (COI). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Sjoerd AS Stufkens

Departamento de Cirugía Ortopédica y Medicina Deportiva. Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC). Sede AMC. Universidad de Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Ciencias del Movimiento de Ámsterdam. Programas de Deporte y Salud Musculoesquelética. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Centro Académico de Medicina Deportiva Basada en la Evidencia (ACES). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Colaboración de Ámsterdam para la Salud y la Seguridad en el Deporte (ACHSS). Centro de Investigación del Comité Olímpico Internacional (COI). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Gino MMJ Kerkhoffs

Departamento de Cirugía Ortopédica y Medicina Deportiva. Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC). Sede AMC. Universidad de Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Ciencias del Movimiento de Ámsterdam. Programas de Deporte y Salud Musculoesquelética. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Centro Académico de Medicina Deportiva Basada en la Evidencia (ACES). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Colaboración de Ámsterdam para la Salud y la Seguridad en el Deporte (ACHSS). Centro de Investigación del Comité Olímpico Internacional (COI). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Ethical responsibilities

Conflicts of interest. The author Prof. dr. G.M.M.J. Kerkhoffs declare the following conflicts of interest: Consultant Arthrex, Naples.

Financial support. This study has received no financial support.

Protection of people and animals. The authors declare that this research has not involved human or animal experimentation.

Data confidentiality. The authors declare that the protocols of their work centre referred to the publication of patient information have been followed.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Referencias bibliográficas

-

1Blom RP, Mol D, van Ruijven LJ, et al. A Single Axial Impact Load Causes Articular Damage That Is Not Visible with Micro-Computed Tomography: An Ex Vivo Study on Caprine Tibiotalar Joints. Cartilage. 2021;13(2_suppl):1490s-1500s.

-

2Hintermann B, Boss A, Schafer D. Arthroscopic findings in patients with chronic ankle instability. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(3):402-9.

-

3Hintermann B, Regazzoni P, Lampert C, et al. Arthroscopic findings in acute fractures of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(3):345-51.

-

4Rikken QGH, Kerkhoffs G. Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: An Individualized Treatment Paradigm from the Amsterdam Perspective. Foot Ankle Clin. 2021;26(1):121-36.

-

5Kerkhoffs G, Karlsson J. Osteochondral lesions of the talus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(9):2719-20.

-

6Dahmen J, Karlsson J, Stufkens SAS, Kerkhoffs G. The ankle cartilage cascade: incremental cartilage damage in the ankle joint. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29(11):3503-7.

-

7Reilingh M, van Bergen C, Dijk vN. Diagnosis and treatment of osteochondral defects of the ankle. South African Orthopaedic J. 2009;8:44-50.

-

8Verhagen RA, Maas M, Dijkgraaf MG, et al. Prospective study on diagnostic strategies in osteochondral lesions of the talus. Is MRI superior to helical CT? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(1):41-6.

-

9Van Bergen CJ, Gerards RM, Opdam KT, et al. Diagnosing, planning and evaluating osteochondral ankle defects with imaging modalities. World J Orthop. 2015;6(11):944-53.

-

10Yasui Y, Hannon CP, Fraser EJ, et al. Lesion Size Measured on MRI Does Not Accurately Reflect Arthroscopic Measurement in Talar Osteochondral Lesions. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019;7(2):2325967118825261.

-

11Van Bergen CJ, Tuijthof GJ, Maas M, et al. Arthroscopic accessibility of the talus quantified by computed tomography simulation. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2318-24.

-

12Meftah M, Katchis SD, Scharf SC, et al. SPECT/CT in the management of osteochondral lesions of the talus. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32(3):233-8.

-

13Leumann A, Valderrabano V, Plaass C, et al. A novel imaging method for osteochondral lesions of the talus--comparison of SPECT-CT with MRI. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(5):1095-101.

-

14Raikin SM, Elias I, Zoga AC, et al. Osteochondral lesions of the talus: localization and morphologic data from 424 patients using a novel anatomical grid scheme. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28(2):154-61.

-

15Van Diepen PR, Smithuis FF, Hollander JJ, et al. Reporting of Morphology, Location, and Size in the Treatment of Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus in 11,785 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cartilage. 2024:19476035241229026.

-

16Rikken QGH, Wolsink LME, Dahmen J, et al. 15% of Talar Osteochondral Lesions Are Present Bilaterally While Only 1 in 3 Bilateral Lesions Are Bilaterally Symptomatic. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2022;104(18):1605-13.

-

17Dombrowski ME, Yasui Y, Murawski CD, et al. Conservative Management and Biological Treatment Strategies: Proceedings of the International Consensus Meeting on Cartilage Repair of the Ankle. Foot Ankle Int. 2018;39(1):9s-15s.

-

18Zengerink M, Struijs PA, Tol JL, van Dijk CN. Treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(2):238-46.

-

19Savage-Elliott I, Ross KA, Smyth NA, et al. Osteochondral lesions of the talus: a current concepts review and evidence-based treatment paradigm. Foot Ankle Spec. 2014;7(5):414-22.

-

20Ramponi L, Yasui Y, Murawski CD, et al. Lesion Size Is a Predictor of Clinical Outcomes After Bone Marrow Stimulation for Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: A Systematic Review. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(7):1698-705.

-

21Lambers KTA, Dahmen J, Reilingh ML, et al. No superior surgical treatment for secondary osteochondral defects of the talus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(7):2158-70.

-

22Dahmen J, Lambers KTA, Reilingh ML, et al. No superior treatment for primary osteochondral defects of the talus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(7):2142-57.

-

23Hannon CP, Bayer S, Murawski CD, et al. Debridement, Curettage, and Bone Marrow Stimulation: Proceedings of the International Consensus Meeting on Cartilage Repair of the Ankle. Foot Ankle Int. 2018;39(1):16s-22s.

-

24D'Hooghe P, Murawski CD, Boakye LAT, et al. Rehabilitation and Return to Sports: Proceedings of the International Consensus Meeting on Cartilage Repair of the Ankle. Foot Ankle Int. 2018;39(1_suppl):61s-67s.

-

25Murawski CD, Foo LF, Kennedy JG. A Review of Arthroscopic Bone Marrow Stimulation Techniques of the Talus: The Good, the Bad, and the Causes for Concern. Cartilage. 2010;1(2):137-44.

-

26O'Driscoll SW. The healing and regeneration of articular cartilage. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(12):1795-812.

-

27Shimozono Y, Coale M, Yasui Y, et al. Subchondral Bone Degradation After Microfracture for Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: An MRI Analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(3):642-8.

-

28Toale J, Shimozono Y, Mulvin C, et al. Midterm Outcomes of Bone Marrow Stimulation for Primary Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: A Systematic Review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019;7(10):2325967119879127.

-

29Hollander JJ, Dahmen J, Emanuel KS, et al. The Frequency and Severity of Complications in Surgical Treatment of Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 6,962 Lesions. Cartilage. 2023;14(2):180-97.

-

30Rikken QGH, Aalders MB, Dahmen J, et al. Ten-Year Survival Rate of 82% in 262 Cases of Arthroscopic Bone Marrow Stimulation for Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2024;106(14):1268-76.

-

31Rikken QGH, Dahmen J, Stufkens SAS, Kerkhoffs G. Satisfactory long-term clinical outcomes after bone marrow stimulation of osteochondral lesions of the talus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29(11):3525-33.

-

32Guney A, Akar M, Karaman I, et al. Clinical outcomes of platelet rich plasma (PRP) as an adjunct to microfracture surgery in osteochondral lesions of the talus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(8):2384-9.

-

33Murphy EP, Fenelon C, McGoldrick NP, Kearns SR. Bone Marrow Aspirate Concentrate and Microfracture Technique for Talar Osteochondral Lesions of the Ankle. Arthrosc Tech. 2018;7(4):e391-e396.

-

34Klein C, Dahmen J, Emanuel KS, et al. Limited evidence in support of bone marrow aspirate concentrate as an additive to the bone marrow stimulation for osteochondral lesions of the talus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31(12):6088-103.

-

35Deal JB Jr., Patzkowski JC, Groth AT, et al. Early vs Delayed Weightbearing After Microfracture of Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: A Prospective Randomized Trial. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2019;4(2):2473011419838832.

-

36Song M, Li S, Yang S, et al. Is Early or Delayed Weightbearing the Better Choice After Microfracture for Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus? A Meta-analysis and Systematic Review. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2021;60(6):1232-40.

-

37Anders S, Lechler P, Rackl W, et al. Fluoroscopy-guided retrograde core drilling and cancellous bone grafting in osteochondral defects of the talus. Int Orthop. 2012;36(8):1635-40.

-

38Takao M, Innami K, Komatsu F, Matsushita T. Retrograde cancellous bone plug transplantation for the treatment of advanced osteochondral lesions with large subchondral lesions of the ankle. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(8):1653-60.

-

39Reilingh ML, Murawski CD, DiGiovanni CW, et al. Fixation Techniques: Proceedings of the International Consensus Meeting on Cartilage Repair of the Ankle. Foot Ankle Int. 2018;39(1_suppl):23s-27s.

-

40Park CH, Song KS, Kim JR, Lee SW. Retrospective evaluation of outcomes of bone peg fixation for osteochondral lesion of the talus. Bone Joint J. 2020;102-b(10):1349-53.

-

41Reilingh ML, Lambers KTA, Dahmen J, et al. The subchondral bone healing after fixation of an osteochondral talar defect is superior in comparison with microfracture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(7):2177-82.

-

42Kumai T, Takakura Y, Kitada C, et al. Fixation of osteochondral lesions of the talus using cortical bone pegs. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84(3):369-74.

-

43Fuchs M, Vosshenrich R, Dumont C, Sturmer KM. Refixation of osteochondral fragments using absorbable implants. First results of a retrospective study. [German]. Chirurg. 2003;74(6):554-61.

-

44Kaplonyi G, Zimmerman I, Frenyo AD, et al. The use of fibrin adhesive in the repair of chondral and osteochondral injuries. Injury. 1988;19(4):267-72.

-

45Lambers KTA, Dahmen J, Reilingh ML, et al. Arthroscopic lift, drill, fill and fix (LDFF) is an effective treatment option for primary talar osteochondral defects. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(1):141-7.

-

46Lenz CG, Tan S, Carey AL, et al. Matrix-Induced Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (MACI) Grafting for Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus. Foot Ankle Int. 2020;41(9):1099-105.

-

47Baums MH, Heidrich G, Schultz W, et al. Autologous chondrocyte transplantation for treating cartilage defects of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(2):303-8.

-

48Cherubino P, Grassi FA, Bulgheroni P, Ronga M. Autologous chondrocyte implantation using a bilayer collagen membrane: a preliminary report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2003;11(1):10-5.

-

49Baums MH, Heidrich G, Schultz W, et al. The surgical technique of autologous chondrocyte transplantation of the talus with use of a periosteal graft. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89 Suppl 2 Pt.2:170-82.

-

50Schneider TE, Karaikudi S. Matrix-induced Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (MACI) grafting for osteochondral lesions of the talus. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30(9):810-4.

-

51Saris DB, Vanlauwe J, Victor J, et al. Characterized chondrocyte implantation results in better structural repair when treating symptomatic cartilage defects of the knee in a randomized controlled trial versus microfracture. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(2):235-46.

-

52Gottschalk O, Altenberger S, Baumbach S, et al. Functional Medium-Term Results After Autologous Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis for Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: A 5-Year Prospective Cohort Study. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2017;56(5):930-6.

Descargar artículo:

Licencia:

Este contenido es de acceso abierto (Open-Access) y se ha distribuido bajo los términos de la licencia Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND (Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional) que permite usar, distribuir y reproducir en cualquier medio siempre que se citen a los autores y no se utilice para fines comerciales ni para hacer obras derivadas.

Comparte este contenido

En esta edición

- Anterior ankle arthroscopy at its best

- Foot and ankle arthroscopy, a consolidated and expanding reality

- The history and current concepts of ankle arthroscopy

- Current status of anterior ankle impingement

- Arthroscopic treatment of chronic lateral ankle instability

- Managing osteochondral lesions of the talus with anterior ankle arthroscopy

- Role of arthroscopy in syndesmosis injuries

- Role of arthroscopy in the treatment of ankle fractures

- Anterior arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis

- The use of needle arthroscopy in the ankle

- The letter pi on the ankle

Más en PUBMED

Más en Google Scholar

Revista Española de Artroscopia y Cirugía Articular está distribuida bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional.