Anterior arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis

Artrodesis artroscópica anterior de tobillo

Resumen:

En las fases avanzadas de la artrosis de tobillo, el tratamiento mediante artrodesis sigue siendo considerado el gold standard. El objetivo de la artrodesis es obtener la fusión ósea con una alineación adecuada, proporcionando un apoyo plantígrado, un tobillo estable y una articulación indolora.

Las mejoras en el instrumental artroscópico y el perfeccionamiento de la técnica han permitido, desde su primera descripción hace 40 años, posicionar al procedimiento artroscópico como una referencia para el tratamiento de la patología degenerativa del tobillo.

Incluso, en algunas variables y para indicaciones concretas, ha mostrado superioridad al procedimiento abierto, por lo que la evidencia actual respalda el abordaje artroscópico para los procedimientos de fusión articular. El cirujano ortopédico especializado en el pie y tobillo debe conocer y profundizar en el dominio de la técnica.

El artículo repasa las indicaciones y conceptos clave de la artrodesis artroscópica anterior de tobillo, señala los aspectos más importantes de la técnica quirúrgica y revisa algunas de las publicaciones más relevantes sobre el tema.

Nivel de evidencia: nivel V.

Abstract:

In the advanced stages of ankle osteoarthritis, treatment in the form of arthrodesis is still considered the gold standard. The aim of arthrodesis is to produce bone fusion with proper alignment, affording plantigrade support, a stable ankle, and a painless joint.

Improvements in arthroscopic instrumentation and refinement of the technique have, since its first description 40 years ago, positioned the arthroscopic procedure as a reference for the treatment of degenerative ankle disease.

In relation to some variables and for specific indications, it has even shown superiority to the open procedure; accordingly, the current evidence supports the arthroscopic approach for joint fusion procedures. The orthopedic foot and ankle surgeon must know and master the technique.

The present article reviews the indications and key concepts of anterior arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis, points out the most important aspects of the surgical technique, and reviews some of the most relevant publications on the subject.

Level of evidence: level V.

Introduction

Degenerative disease of the ankle joint has a significant impact on patient quality of life, due to the pain, functional limitation and joint stiffness characteristic of this disorder.

The main underlying origin is post-traumatic, affecting patients who are still of working age(1). These cases are usually secondary to fractures, joint instabilities, or a combination of both(2).

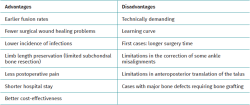

Traditionally, the treatment of choice for ankle osteoarthritis refractory to conservative treatment has been open tibiotalar arthrodesis (OTA). Common complications of these procedures include wound and soft tissue problems, infections and the lack of consolidation, regardless of the fixation method used(3).

The improvement of arthroscopic techniques and the evolution of the instruments used have made it possible to develop these joint fusion procedures adopting an arthroscopic approach. The first description was published by Schneider in 1983(4).

Over the years, it has positioned itself as a less invasive procedure that reduces damage to the periarticular soft tissues, decreases postoperative pain rates, better preserves periarticular vascularization, reduces bleeding, shortens hospital stay and minimizes surgical wound complications. Some of the published series have also reported a faster fusion rate compared to open techniques(5).

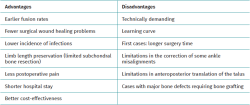

Another advantage of arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis (AAA) is the preservation of the fibula, increasing stability of fusion, and allowing future scenarios of conversion to an ankle prostheses in selected cases(6) (Table 1).

The present study provides a technical review of AAA, analyzing the indications, the key concepts of the surgical technique, and the published advantages of arthroscopic tibiotalar fusion compared to open arthrodesis.

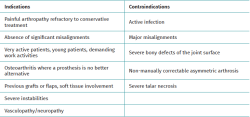

Indications and contraindications

Any patient presenting with symptomatic ankle osteoarthritis, with pain on passive mobilization of the joint, advanced tibiotalar involvement, and preservation of the mechanical axis after manual reduction of the joint, is a candidate for AAA(7) (Table 2).

Arthroscopic techniques may be indicated in patients with potential healing problems and soft tissue involvement, in diabetic patients, in individuals with flaps or grafts resulting from previous surgery, and even in patients with a history of infection or mild avascular necrosis.

The contraindications are the same as for any other surgical arthrodesis procedure(7). The presence of active infection is considered an absolute contraindication. It should be noted that arthropathies with supra- or infra-malleolar angular deformities requiring correction of the mechanical axis are contraindications for in situ arthrodesis if the latter is to be performed as a stand-alone procedure.

In cases of ankle misalignment with an abnormal talar tilt (increased tibiotalar angle), the tilt can be corrected arthroscopically through planned soft tissue release and adequate stabilization after intra-articular correction(8).

Recent studies have reported that arthroscopic ankle fusion produces satisfactory fusion and deformity correction rates in ankles with coronal and sagittal deformities even greater than15°(8,9,10,11).

According to these authors, it appears that the indication for AAA could tolerate a considerable degree of preoperative deformity depending on its reducibility. They argue that instead of deciding on the basis of the radiological deformity angle, the deformity angle after manual reduction should be considered as a better parameter to establish a contraindication for ankle arthrodesis.

Another classically established contraindication is the presence of severe avascular necrosis of the talus. Zvijac(12) published that the presence of avascular necrosis of the talus exceeding 30% is one of the risk factors for AAA failure.

Similarly, bony defects greater than one-third of the talar dome are considered another relative contraindication, as advocated by Myerson and Quill(13).

Preoperative planning

The physical examination should include careful inspection of the condition of the soft tissues, the identification of signs of arteriopathy or peripheral neuropathy, and assessment of the hindfoot. Pain and the range of active and passive motion should be assessed. In cases with intra-articular incongruities, the ability of preoperative manual reducibility should be evaluated.

As with any ankle joint procedure, it is mandatory to analyze proximal alignment, infra-malleolar alignment and intra-articular misalignment.

The plain radiographic study should include posteroanterior and lateral views of the ankle and foot under weight bearing conditions, and a mortise projection. We must also have telemetry of the limb to assess proximal alignment and a Saltzman or long axial view to assess infra-malleolar alignment(14).

The supra-malleolar alignment of the ankle should be evaluated in the coronal and sagittal planes, measuring the anterior distal tibial angle and the lateral distal tibial angle, respectively.

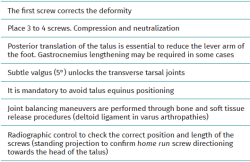

In the anterior ankle projection we evaluate the talar tilt or angle of inclination of the talus, which is increased in incongruent intra-articular injuries (Figure 1).

reacae.32284.fs2505013en-figure1.png

Figure 1. A: anterior distal tibial angle, between the anatomical axis of the tibia in the posteroanterior plane and the line of the distal joint surface of the tibia; B: talar tilt angle, formed between the line of the tibial joint surface and the line of the talar joint surface. Assesses joint congruency; C: lateral distal tibial angle, between the lateral anatomical axis of the tibia and the line of the lateral distal joint surface of the tibia.

Hindfoot alignment must be accurately assessed, considering the correction of axial deviations before or in conjunction with any tibiotalar fusion procedure.

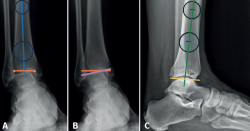

We must observe whether, in the lateral projections, there is an anterior translation of the talus, which often occurs in these chronic degenerative phenomena associated with instabilities (Figure 2).

Computed tomography (CT) and single photon emission tomography (SPECT)-CT are the most useful complementary tests to plain radiography, since they allow characterization of the osteoarticular lesions both in the ankle and in the rest of the neighbouring joints, as well as the evaluation of alterations in the different bone structures (osteophytes, bone cysts, loss of bone stock , etc.). Some studies argue that SPECT-CT has significantly higher inter- and intra-observer reliability compared to CT(15).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows for more accurate assessment of the cartilage and, although not routinely requested, would be indicated in cases with a suspicion or history of necrosis of the talus or tibia.

All the findings should form part of the surgical treatment planning.

Surgical technique

Preparation and positioning of the patient

Antibiotic prophylaxis is administered prior to surgery according to the hospital protocol.

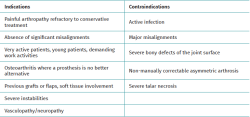

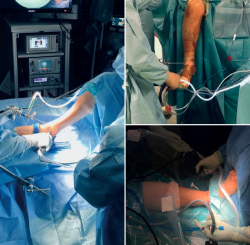

The patient is placed in the supine position. Depending on the surgeon, the limb can be positioned in two ways. One option is with the heel resting on the edge of the operating table. In this case, a support is placed to slightly elevate the ipsilateral hip, neutralize external rotation and position the ankle in neutral.

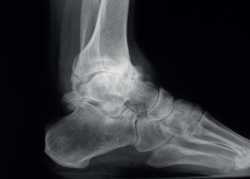

Another option preferred by some authors is, having removed the leg supports from the operating table, to clamp the thigh of the limb with a leg brace so that the hip is flexed about60°, with the knee flexed and mobile, allowing the ankle to fall free(16,17) (Figure 3).

reacae.32284.fs2505013en-figure3.png

Figure 3. Different limb positioning for arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis procedures. Depending on the surgeon's preference, a thigh brace may be used and, with the knee in flexion, the ankle may be left to hang down under gravity. Another option is to work in the semi-flexed knee position on the operating table. Finally, the traditional supine position on the operating table, with the knee in extension.

A tourniquet is used on the thigh with appropriate padding.

The image intensifier is prepared and strategically positioned.

Antiseptic washing is carried out, placing sterile drapes, and the lower extremity from the knee to the toes is left free and accessible.

Irrigation can be by gravity or using a pump.

Instruments

- We use a 4.0 mm (30°) arthroscope.

- Motorized synoviotome: shaver with serrated inner blade and smooth outer blade, or shaver with double serrated blade.

- Motorized spherical or cylindrical burrs.

- Osteotomes, chisels, spoons and curettes (straight and curved).

- A set of screws with partial and full threading, 6.5 to 7 mm in diameter.

- Ankle distraction strap (not usually necessary).

Extras

- Cancellous bone graft (auto- or allograft).

- Bone graft substitute.

- Demineralized bone matrix.

Portals

- Standard anteromedial and anterolateral portals are used.

- A volume of 15-20 ml of saline solution can be insufflated as a preliminary step to distend the capsule and create space.

- It is advisable to use a marker pen to trace the path of the medial dorsal cutaneous nerve, which is visible superficially in many cases during plantar flexion and inversion of the ankle, in order to minimize the risk of injuring it on performing the anterolateral portal.

- During surgery, additional portals may be required to access the medial and lateral recesses. In some cases, posteromedial or posterolateral accessory portals may be needed for curettage of the most posterior portion of the talus and tibia.

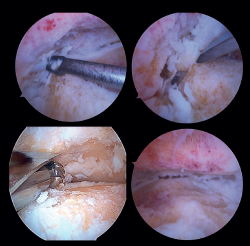

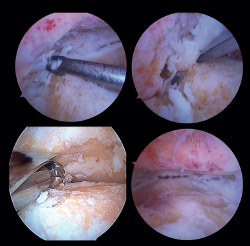

Preparation of the joint surfaces (Figure 4)

- In case of significant synovitis or arthrofibrosis, initial debridement is performed with a synoviotome allowing visualization of the joint.

- Large anterior osteophytes may be present, and their initial resection may require the use of a burr, curette or osteotome, taking care not to damage the anterior neurovascular structures. Resecting them from the start sometimes improves dorsiflexion of the talus and affords a better neutral position in the sagittal plane, as well as better visualization of the operating field.

It is useful to exchange viewing and working portals to access the full extent of the cartilage surfaces and to check complete resection.

The vaporizer is useful in cases of severe fibrotic impingement, which is characteristic of post-traumatic or second surgery scenarios, but again we should work as close to bone or joint space as possible, in order to avoid anterior tissue injury. - It is usually not necessary to use a distraction device to open the joint, since the joint space will progressively grow as the remaining joint cartilage is resected.

- Surgical curettage is performed, with chondral delamination and excision of the cartilage tissue until a viable cancellous bone bed is obtained. This can be done with or without motorized burr support, depending on each case.

- For preparation of the recesses, medial and lateral accessory portals can be used for drilling or curettage of both the medial aspect of the distal fibula and the lateral aspect of the medial malleolus.

- In cases of advanced syndesmotic lesions with marked widening, syndesmotic fusion is recommended, especially in cases of valgus arthropathy. The tibiofibular joint surface is typically prepared with one of the chosen shaver terminals.

- All residues are removed with specific instruments. Perforations can be added to obtain bleeding areas in the subchondral bone.

- Soft tissue release is performed, if necessary. This fundamentally applies to the deltoid ligament when there is a varus component in the joint disorder.

- In patients with major defects or poor bone stock, structural auto- or allografts are used on a case-by-case basis. We may require widening of the portals for their placement or mini-arthrotomies.

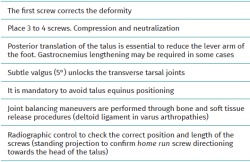

Ankle positioning

The optimal position for ankle arthrodesis is a subtle valgus of 5°, neutral dorsiflexion and an external rotation of 5-10°. In particular, subtle valgus is beneficial as it unlocks the transverse tarsal joints(18)

A posterior translation of the talus is biomechanically more favorable and decreases the lever arm in the midfoot.

In some cases, gastrocnemius lengthening or calcaneal tendon lengthening may be necessary for the reduction of severe cases of equinus, valgus or anterior translation. In other cases, partial or subtotal release of the deltoid ligament may be indicated.

Once the desired position is obtained, preliminary fixation is made using Kirschner pins, with intraoperative fluoroscopic confirmation in the anteroposterior and lateral planes.

Fixation methods

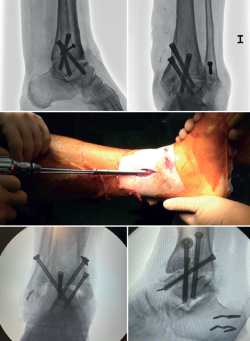

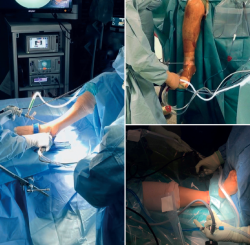

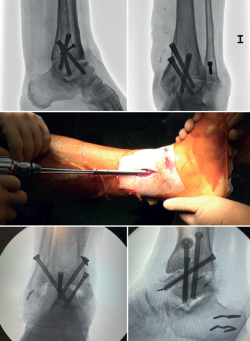

In arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis, the use of percutaneously placed compression screws is the technique of choice (Figure 5).

Most authors consider the use of cannulated screws (3 to 4) to be the ideal fixation method. The diameters of the chosen screws should be between 6 and 7 mm. This technique achieves 85-100% fusion and 84-95% patient satisfaction rates(19).

Van Dijk, Kerkhoffs et al.(20) reported excellent results with the use of three screws as the standardized method for ankle arthrodesis.

Screw configuration and placement

Depending on the deformity involved and according to preoperative planning, screw placement is carried out starting with the compression screw that counteracts the deformity.

In other words, in arthropathies with a varus component, we would start with a lateral screw, while in valgus misalignments the recommendation is to place the first screw from the medial side. The second screw should be on the side opposite to the first. Both should provide adequate compression between the joint surfaces(17).

In general, a minimum of three screws are used. The third screw is the so-called home run screw, the importance of which has been highlighted by Holt et al.(21). It is directed across the ankle from the posterior part of the tibia to the neck of the talus. A fourth screw may be used as an augmentation of the first, counteracting the main deformity.

Goetzmann et al.(22), in their review of 111 cases, supported the use of at least three screws for fixation of arthroscopic tibiotalar arthrodesis. The addition of a third screw appears to be associated with a lower risk of pseudarthrosis and shorter consolidation time. These effects can be attributed to an increased stability of the construct.

Glick, Myerson(23) et al. reported that the configuration conferring the greatest rigidity to the osteosynthesis comprises two screws from medial and one from the lateral side.

In cases where there is anterior translation of the talus, good resection of the posterior tibial malleolus is important to allow for reduction and proper positioning of the talus. Another useful technique is, in the supine position, to place a support under the distal tibia leaving the heel free to be manually moved posteriorly.

In some of these cases with anterior translation of the talus, and contrary to the usual recommendations, it may be useful to first position the posteroanterior screw with partial threading, to reduce the talus from anterior to posterior and align it with the lateral longitudinal axis.

Definitive anteroposterior, mortise, lateral ankle, dorsoplantar and oblique foot radiographs are obtained to confirm correct reduction, and the position and length of the screws, especially the home run screw (Table 3).

Postoperative period and evolution

After surgery, the ankle is immobilized with a splint. Checks and dressings are carried out during the first three weeks until the stitches can be removed. The usual consensus is to avoid weight bearing for the first 6 weeks, although some authors allow partial weight bearing between weeks 4 and 8, delaying full weight bearing until more than 50% fusion of the joint surface is observed. Standardized follow-ups are usually performed at 3, 6 and 9 months and one year postsurgery(24).

Discussion

The published functional outcomes and satisfaction rates of patients undergoing AAA are good, with most series reporting favorable results (76-98%) over mid- and long-term follow-up after these procedures(25). With an average follow-up of 9 years, Hendrickx et al.(20) reported a satisfaction rate of 91% in their series of 60 patients who underwent AAA, confirming the persistence of the benefits of this procedure in the long term.

Open techniques have been the gold standard treatment for ankle arthropathy for decades. Since the introduction of AAA, many studies have reported good results and even some advantages compared to the open procedure, based on shorter hospital stay, the fusion rates obtained, fewer soft tissue complications, and less postoperative pain(25).

In some studies, a critical reading of possible selection bias should be made, since the degree of deformity, the presence of previous infection or vascular status are determining factors in patient selection(26,27,28). Such possible bias would favor the choice of less complex cases for arthroscopic procedures.

Fusion rates

The arthroscopic procedure is able to consistently achieve high fusion rates between 91-100%. In the series published by Gougoulias et al.(10), the consolidation rate was as high as 98%, with no differences in terms of fusion when compared to open surgery.

Several systematic reviews have been published in recent years, comparing the clinical efficacy of AAA with OTA. Bai et al.(29) analyzed 18 studies including 1102 patients, 551 of whom were treated via the open approach and 551 by arthroscopy. They reported fusion rates of 83.2% for the open group and 95.1% for the arthroscopic group. The authors attribute this finding to the minimally invasive nature of the arthroscopic procedure, which minimizes soft tissue injury and favors optimal conditions for bone consolidation.

In the systematic review published by Lorente et al.(30), 994 patients were examined, of whom 487 underwent open arthrodesis and 507 were treated arthroscopically. The fusion rates were 78.5% for the open techniques and 92.3% for the arthroscopic methods.

Mok et al.(31) included 507 patients (234 open, 273 arthroscopic). They reported fusion rates of 79% for the open techniques and 91% for the arthroscopic procedures.

However, these differences are not in line with the results reported in the systematic review published by Vandenheuvel et al.(32) on the fusion rates of open ankle arthrodesis procedures. These authors reviewed 38 studies, including 1250 patients, and observed fusion rates above 95%, regardless of the open approach used.

Consolidation time

The consolidation time reported for AAA ranges in the published series from 9 weeks to 3.5 months(25,33). Some studies have reported a shorter consolidation time with the arthroscopic technique compared to the open procedure(29,30,31).

The definition of consolidation and fusion is not homogeneous between series, however. Some publications use simple radiographic criteria instead of CT images, with the consequent bias this would entail. Given the difficulty and ethical conflict of performing serial CT scans in postoperative controls, the consensus for the definition of fusion should bring together clinical and radiological concepts: a stable and painless ankle on weight bearing, no postoperative loss of correction, no alterations of internal fixation, and radiological criteria demonstrating the presence of bone bridging.

Duration of the procedure

The average duration of the procedure varies according to the literature source. Machado da Silva(34) reported an average duration of 81.4 minutes, while Towshend(35) reported 99 minutes, and the study with the longest time taken for the procedure reported 140.5 minutes(36). Surgeon experience and the learning curve play an important role in this aspect of the procedure.

Postoperative complication rates

Analysis of the postoperative complications in the published studies reveals a consistent trend in favor of arthroscopic techniques over open approaches, highlighting the ability of AAA to achieve comparable surgical outcomes with significantly fewer adverse events. Bai et al.(29) reported complication rates of 12.8% for open approaches versus 6.1% for the arthroscopic technique. Lorente et al.(30) in turn reported complication rates of 15.4% for the open techniques and 8.5% for the arthroscopic approaches. Park et al.(37) found that complications occurred in 16% of the patients when using open techniques and in 10% of the cases when using arthroscopy.

Hospital stay

In relation to the days of hospital stay, arthroscopic procedures tend to involve on average 2 days less hospital stay compared to open techniques (3 and 5 days on average, respectively), which would have a direct impact in terms of cost savings and the more efficient use of resources(25,38,39,40).

Degree of deformity and indication

Schmid, Younger et al.(41) published their work on the influence of preoperative deformity upon the results of open and arthroscopic arthrodesis. They analyzed 97 patients who underwent ankle fusion procedures (62 arthroscopic and 35 open) with a follow-up of two years after surgery. They found that patients selected for arthroscopic procedures had less deformity at distal tibia level. The use of open procedures for cases with more complex deformities seems to be a pattern that is repeated in most studies and certainly should be considered when analyzing the results.

Nielsen et al.(42) compared 58 arthroscopies with 49 open procedures, with similar inclusion criteria, but it was seen that the open group had greater coronal plane misalignments (varus/valgus), which would imply the aforementioned selection bias.

Several authors have advocated a change in trend in choosing the degree of deformity as a contraindication for the AAA procedure. This paradigm shift is based on assessing the preoperative deformity in terms of its reducibility. Thus, instead of deciding on the basis of the static radiological deformity angle under weight bearing conditions, the deformity angle after manual reduction should be considered as a better parameter to establish a formal contraindication to ankle arthrodesis via an arthroscopic procedure(17).

Despite the preoperative radiological differences published in the series by Schmid(41), the clinical results were similar in both groups at the end of follow-up, as was the radiological correction achieved. Preoperative deformity in the coronal or sagittal plane did not influence the clinical outcome or the functional or satisfaction scores at the end of follow-up. The only variable that influenced the results was the level of dysfunction reported on the preoperative scales.

Arthrodesis and kinematic changes. Alternatives

In the long term, ankle arthrodesis will produce relevant alterations in gait kinematics. Due to the tibiotalar fusion, motion in the sagittal plane decreases. Biomechanical compensation through the subtalar joint is known to compensate for the absence of ankle motion. The increased shear forces transmitted through the subtalar and mid-tarsal joints will lead to the subsequent development of osteoarthritis in the neighboring joints, especially in the subtalar joint(43,44). For this reason, arthroplasty procedures should be considered as an alternative in these patients, if permitted by the individual case conditions(45,46,47).

Conclusions

Ankle arthrodesis remains the most common surgical procedure for the management of ankle osteoarthritis today. The aim is to obtain a stable and pain-free ankle with plantigrade support, and to achieve efficient gait after fusion.

Arthroscopic arthrodesis is a reproducible option for the treatment of ankle osteoarthritis. It achieves high fusion rates, shorter consolidation times and adequate deformity correction, with the advantages of a shorter hospital stay, less bleeding and fewer complications from soft tissue lesions.

The inherent advantages afforded by its minimally invasive nature reduce soft tissue trauma and promote optimal conditions for bone consolidation, allowing for precise joint preparation.

Tablas

Figuras

Figure 1. A: anterior distal tibial angle, between the anatomical axis of the tibia in the posteroanterior plane and the line of the distal joint surface of the tibia; B: talar tilt angle, formed between the line of the tibial joint surface and the line of the talar joint surface. Assesses joint congruency; C: lateral distal tibial angle, between the lateral anatomical axis of the tibia and the line of the lateral distal joint surface of the tibia.

Figure 2. Anterior translation of the talus, characteristic of tibiotalar arthropathies secondary to chronic instabilities.

Figure 3. Different limb positioning for arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis procedures. Depending on the surgeon's preference, a thigh brace may be used and, with the knee in flexion, the ankle may be left to hang down under gravity. Another option is to work in the semi-flexed knee position on the operating table. Finally, the traditional supine position on the operating table, with the knee in extension.

Figure 4. Preparation of the joint surfaces using different types of instruments: curettes, chisels or motorized drills. Final view after obtaining an optimal subchondral bed of the tibiotalar joint.

Información del artículo

Cita bibliográfica

Autores

Carlos Álvarez Gómez

Servicio de Cirugía Ortopédica y Traumatología. Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla. Santander

Cirugía Ortopédica y Traumatología. Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Hospital Sanitas CIMA. Barcelona

Ethical responsibilities

Conflicts of interest. The author states that he has no conflicts of interest.

Financial support. This study has received no financial support.

Protection of people and animals. The author declares that the procedures carried out abided with the ethical standards of the responsible human experimentation committee and in accordance with the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data confidentiality. The author declares that the protocols of his work center referred to the publication of patient information have been followed.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The author declares that no patient data appear in this article.

Referencias bibliográficas

-

1Valderrabano V, Horisberger M, Russell I, et al. Etiology of ankle osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:1800-6.

-

2Saltzman CL, Salamon ML, Blanchard GM, et al. Epidemiology of ankle arthritis. Report of a consecutive series of 639 patients from a tertiary orthopaedic center. Iowa Orthop J. 2005;25:44-6.

-

3Rodríguez-Merchán EC, Ribbans WJ, Olmo-Jiménez JM, Delgado-Martínez AD. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis for end-stage ankle osteoarthritis. EFORT Open Rev. 2025;10(5):213-23.

-

4Schneider D. Arthroscopic ankle fusion. Arthroscopic Video J. 1983, 3.

-

5Cottino U, Collo G, Morino L, et al. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis: a review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2012;5(2):151-5.

-

6Vilá y Rico J, Mellado Romero MA, Iglesias Durán E. Artrodesis artroscópica de tobillo. Mon Act Soc Esp Med Cir Pie Tobillo. 2014;6:25-31.

-

7Glazebrook MA, Ganapathy V, Bridge MA, et al. Evidence-based indications for ankle arthroscopy. Arthroscopy 2009;25(12):1478-90.

-

8Le V, Veljkovic A, Salat P, et al. Ankle Arthritis. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2019;4(3):1-16.

-

9Dannawi Z, Nawabi DH, Patel A, et al. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis: are results reproducible irrespective of pre-operative deformity? Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;17(4):294-9.

-

10Gougoulias NE, Agathangelidis FG, Parsons SW. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28(6):695-706.

-

11Schmid T, Krause F, Penner MJ, et al. Effect of Preoperative Deformity on Arthroscopic and Open Ankle Fusion Outcomes. Foot Ankle Int. 2017;38(12):1301-10.

-

12Zvijac JE, Lemak L, Schurhoff MR, et al. Analysis of arthroscopically assisted ankle arthrodesis. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(1):70-5.

-

13Myerson M, Quill G. Ankle artrhodesis. A comparison of an arthroscopic and an open method of treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;268:84-95.

-

14Stufkens SA, Barg A, Bolliger L, et al. Measurement of the medial distal tibial angle. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32(3):288-93.

-

15Pagenstert GI, Barg A, Leumann AG, et al. SPECT-CT imaging in degenerative joint disease of the foot and ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(9):1191-6.

-

16Rippstein P, Kumar B, Müller M. Ankle arthrodesis using the arthroscopic technique. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2005;17(4-5):442-56.

-

17Leucht AK, Veljkovic A. Arthroscopic Ankle Arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Clin. 2022;27(1):175-97.

-

18Buck P, Morrey BF, Chao EY. The optimum position of arthrodesis of the ankle. A gait study of the knee and ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(7):1052-62.

-

19Winson IG, Robinson DE, Allen PE. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87-B(3):343-7.

-

20Hendrickx RP, Kerkhoffs GM, Stufkens SA, et al. Ankle fusion using a 2-incision, 3-screw technique. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2011;23(2):131-40.

-

21Holt ES, Hansen ST, Mayo KA, et al. Ankle arthrodesis using internal screw fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;(268):21-8.

-

22Goetzmann T, Molé D, Jullion S, et al. Influence of fixation with two vs. three screws on union of arthroscopic tibio-talar arthrodesis: Comparative radiographic study of 111 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102(5):651-6.

-

23Glick JM, Morgan CD, Myerson MS, et al. Ankle arthrodesis using an arthroscopic method: long-term follow-up of 34 cases. Arthroscopy. 1996;12(4):428-34.

-

24Elmlund AO, Winson IG. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Clin. 2015;20(1):71-80.

-

25Fiore PI, Soares S, Seidel A, Garibaldi R. Open vs arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis: a comprehensive umbrella review of outcomes and complications. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol SCI. 2025;29:268-77.

-

26Lee MS, Figas SM, Grossman JP. Arthroscopic Ankle Arthrodesis. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2023;40:459-70.

-

27Saragas NP. Results of arthroscopic arthrodesis of the ankle. Foot Ankle Surg. 2004;10(3):141-3.

-

28Wang C, Xu C, Li M, et al. Arthroscopic ankle fusion only has a limited advantage over the open operation if osseous operation type is the same: a retrospective comparative study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2020;15:80.

-

29Bai Z, Yang Y, Chen S, et al. Clinical effectiveness of arthroscopic vs open ankle arthrodesis for advanced ankle arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e24998.

-

30Lorente A, Pelaz L, Palacios P, et al. Arthroscopic vs. Open Ankle Arthrodesis on Fusion Rate in Ankle Osteoarthritis Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2023;12:3574.

-

31Mok TN, He Q, Panneerselavam S, et al. Open versus arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2020;15:187.

-

32Van den Heuvel SBM, Doorgakant A, Birnie MFN, et al. Open Ankle Arthrodesis: A Systematic Review of Approaches and Fixation Methods. Foot Ankle Surg. 2021;27:339-47.

-

33Morelli F, Princi G, Cantagalli M, et al. Arthroscopic vs open ankle arthrodesis: A prospective case series with seven years follow up. World J Orthop. 2021;18(12):1016-25.

-

34Silva BM, Vasconcelos JB, Bucar HL, et al. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis: clinical results. J Foot Ankle. 2025;19(01):e1811.

-

35Townshend D, Di Silvestro M, Krause F, et al. Arthroscopic versus open ankle arthrodesis: a multicenter comparative case series. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(2):98-102.

-

36Honnenahalli Chandrappa M, Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S. Ankle arthrodesis . Open versus arthroscopic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2017;8(Suppl 2):S71-S77.

-

37Park JH, Kim HJ, Suh DH, et al. Arthroscopic Versus Open Ankle Arthrodesis: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2018;34:988-97.

-

38Xing G, Xu M, Yin J, et al. Effectiveness of Arthroscopically Assisted Surgery for Ankle Arthrodesis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2023;62:398-404.

-

39Jones CR, Wong E, Applegate GR, et al. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis: a 2–15 year follow-up study. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(5):1641-9.

-

40Peterson KS, Lee MS, Buddecke DE. Arthroscopic versus Open Ankle Arthrodesis: A Retrospective Cost Analysis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49(3):242-7.

-

41Schmid T, Krause F, Penner MJ, et al. Effect of Preoperative Deformity on Arthroscopic and Open Ankle Fusion Outcomes. Foot Ankle Int. 2017;38:1301-10.

-

42Nielsen KK, Linde F, Jensen NC. The outcome of arthroscopic and open surgery ankle arthrodesis: a comparative retrospective study on 107 patients. Foot Ankle Surg. 2008;14(3):153-7.

-

43Thomas R. Gait analysis and functional outcomes following ankle arthrodesis for isolated ankle arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(3):526-35.

-

44Wyss C, Zollinger H. The causes of subsequent arthrodesis of the ankle joint. Acta Orthop Belg. 1991;57 suppl 1:22-7.

-

45Haddad SL, Coetzee JC, Estok R, et al. Intermediate and long-term outcomes of total ankle arthroplasty and ankle arthrodesis. A systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(9):1899-905.

-

46Saltzman CL, Kadoko RG, Suh JS. Treatment of isolated ankle osteoarthritis with arthrodesis or the total ankle replacement: a comparison of early outcomes. Clin Orthop Surg. 2010;2(1):1-7.

-

47Goldberg AJ, Chowdhury K, Bordea E, et al. Total Ankle Replacement Versus Arthrodesis for End-Stage Ankle Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(12):1648-57.

Descargar artículo:

Licencia:

Este contenido es de acceso abierto (Open-Access) y se ha distribuido bajo los términos de la licencia Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND (Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional) que permite usar, distribuir y reproducir en cualquier medio siempre que se citen a los autores y no se utilice para fines comerciales ni para hacer obras derivadas.

Comparte este contenido

En esta edición

- Anterior ankle arthroscopy at its best

- Foot and ankle arthroscopy, a consolidated and expanding reality

- The history and current concepts of ankle arthroscopy

- Current status of anterior ankle impingement

- Arthroscopic treatment of chronic lateral ankle instability

- Managing osteochondral lesions of the talus with anterior ankle arthroscopy

- Role of arthroscopy in syndesmosis injuries

- Role of arthroscopy in the treatment of ankle fractures

- Anterior arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis

- The use of needle arthroscopy in the ankle

- The letter pi on the ankle

Más en PUBMED

Más en Google Scholar

Revista Española de Artroscopia y Cirugía Articular está distribuida bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional.