The use of needle arthroscopy in the ankle

El uso de la artroscopia con aguja en el tobillo

Resumen:

La artroscopia con aguja ha ganado cada vez más atención como alternativa mínimamente invasiva a la artroscopia convencional. Con la creciente demanda de artroscopia de tobillo, la artroscopia con aguja podría ayudar a reducir la creciente demanda de procedimientos artroscópicos de tobillo. Los estudios cadavéricos demostraron que la artroscopia con aguja permite visualizar y acceder eficazmente a todas las estructuras importantes de la articulación del tobillo sin causar daños iatrogénicos. Esta investigación fundamental se tradujo en una amplia cartera clínica.

Los resultados clínicos del uso de la artroscopia con aguja para tratar el pinzamiento de tobillo bajo anestesia local han mostrado resultados positivos significativos con complicaciones mínimas. Además, la artroscopia con aguja parece desempeñar un valioso papel de apoyo como método mínimamente invasivo para confirmar la inestabilidad sindesmótica y tratar simultáneamente posibles patologías intraarticulares, así como para mejorar la precisión de la administración intraarticular de agentes inyectables. Además, también puede tener valor diagnóstico en casos de síntomas persistentes en el tobillo en los que la imagen convencional no consigue revelar la patología subyacente. A pesar de estos resultados prometedores, el conjunto actual de pruebas sigue siendo limitado y se necesitan más investigaciones para evaluar los resultados a largo plazo y la rentabilidad.

Abstract:

Needle arthroscopy has gained increased attention as a more minimally invasive alternative to conventional arthroscopy. With the growing demand for ankle arthroscopy, needle arthroscopy might help to better facilitate the pending increase in ankle arthroscopic procedures. Cadaveric studies demonstrated that needle arthroscopy can effectively visualize and access all relevant structures in the ankle joint without causing iatrogenic damage. This fundamental research translated into a broad clinical portfolio.

Clinical results using needle arthroscopy to treat ankle impingement under local anesthesia have shown significant positive outcomes with minimal complications. In addition, needle arthroscopy appears to play a valuable supportive role as a minimally invasive method to confirm syndesmotic instability and concurrently treat potential intra-articular pathologies, as well as to improve the accuracy of intra-articular delivery of injectable agents. Furthermore, it may also offer diagnostic value in cases of persistent ankle symptoms where conventional imaging fails to reveal the underlying pathology. Despite these promising findings, the current body of evidence remains limited, and further research is needed to assess long-term outcomes and cost-effectiveness.

Introduction

The demand for ankle arthroscopy has been steadily increasing, and over the years, its applications have expanded significantly—from simple diagnostic evaluations to advanced reconstructive procedures(1,2). In 2020, the editors of KSSTA highlighted this trend with the clear message: "A Big Wave Is Coming, Be Prepared", predicting continues growth in arthroscopic procedures and emphasizing the need for innovations, such as needle arthroscopy, to respond to this increasing demand(3).

This article provides an overview of needle arthroscopy’s role in intra-articular anterior and posterior ankle joint pathology, including historical background, surgical technique, clinical indication, complications and the pearls & pitfalls. In addition, recent developments in tendoscopy will be briefly addressed.

History

The concept of needle arthroscopy was introduced in the 1990s, with the aim of a more minimally invasive alternative to conventional arthroscopy(4,5). Initially, it was presented as a method for orthopedic surgeons to visualize and evaluate a joint, with the possibility of performing the procedure under local anesthesia.

In 1994, Patton et al. reported one of the first case series involving four patients who underwent in-office needle arthroscopy of the ankle(6). Subsequently, in 2004, Small and Del Gallo highlighted the potential benefits of shifting foot and ankle arthroscopy from a hospital setting to an in-office setting. They recommended in-office foot and ankle arthroscopy for a variety of simple diagnostic and therapeutic indications such as impingement, osteochondral defects and synovitis(7).

Despite its early potential, needle arthroscopy did not gain widespread adoption. This was primarily due to its poor image quality compared to traditional arthroscopy, which compromised diagnostic accuracy. Furthermore, the absence of tailored surgical instruments significantly limited its therapeutic applications. In addition, the system also consisted of large and robust machinery, which further hindered its practical use(8,9).

After a period of silence surrounding needle arthroscopy, 2018 marked a renewed interest in the technique. The introduction of a new novel needle arthroscopic system featuring a disposable chip-on-tip arthroscope redefined the potential of this minimally invasive technique(10). This innovative technology facilitates arthroscopy using a semi-regid durable arthroscope-cannula combination with a total diameter of two millimeters, making the procedure acceptable for the patient under local anesthesia(11-19).

Equipment

The needle arthroscopic system consists of two main components – a disposable handpiece set and a tablet-like, portable control unit (Figure 1). The handpiece contains an all-in-one, semi-rigid, 0-degree needle arthroscope with a built-in LED light source and chip-on-tip technology. It offers also a range of specialized arthroscopic instruments for interventional use, such as a biter, grasper, scissor, probe, and shaver.

Visualization: introduction in a cadaveric setting

The practical use of the needle arthroscopy was first explored in a cadaveric setting, evaluating whether it could effectively visualize and access all relevant structures in the anterior ankle joint without causing iatrogenic damage(20,21). Stornebrink et al.(20) demonstrated that using the anteromedial portal alone provided a complete visualization of the anterior ankle joint. The addition of an anterolateral portal - a working portal- enabled successful biopsies and provided access to 96% of the talar dome and 85% of the tibial plafond.

Furthermore, Inoue et al.(21) examined how different portal placements affect both the visualizable range within the ankle joint and the potential risk of neurovascular injury. Needle arthroscopy via anteromedial or anterolateral portals provides limited contralateral visualization. In contrast, medial midline and anterocentral portals offer superior access, though the latter requires caution due to its proximity to the anterior neurovascular bundle(21,22).

These cadaveric studies showed that the two-millimeter diameter operative arthroscopy of the ankle could be performed safely and effectively. The findings also highlight the importance of planning and precise portal placement to minimize the risk of neurovascular injury while maximizing joint accessibility and visualization.

Surgical technique: general procedure

Positioning and local anesthesia

Anterior Ankle Arthroscopy(23)

The patient is positioned in a supine position on a standard examination table with the foot at the edge of the bed, allowing gravity to assist with joint distention. Relevant surface ankle anatomy is marked on skin, including the medial and lateral malleolus, tibialis anterior tendon, peroneus tertius tendon, and the superficial peroneal nerve. The surgical field is disinfected with an antiseptic solution, and standard sterile draping is applied.

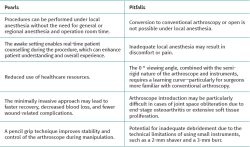

Prior to anesthesia, the standard anteromedial and anterolateral portals are identified by palpation. The anteromedial portal is located at the soft spot, just medial to the anterior tibial tendon and along the anterior joint line. The safest anterolateral portal placement is just lateral to the peroneus tertius or extensor digitorum longus tendon, avoiding the superficial peroneal nerve. The variability of the different branches of the superficial peroneal nerve will place the portal either lateral or medial to its lateral branch (Figure 2).

reacae.32284.fs2509022en-figure2.png

Figure 2. A: right ankle, seen from an anterolateral perspective. Number 2 refers to the anterolateral portal; B: right ankle, seen from an anterior perspective. Number 1 refers to the anteromedial portal, and number 2 refers to the anterolateral portal. (ML, lateral malleolus; MM medial malleolus; N, superficial peroneal nerve; TibA, tibialis anterior muscle tendon).

The planned portals are then infiltrated with local anesthesia, ensuring the entire tract is anaesthetised, from skin to joint capsule, including intra-articular areas. This is important, as the joint capsule is highly innervated.

Posterior ankle arthroscopy(24)

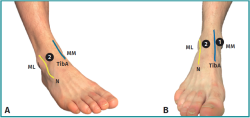

For posterior ankle arthroscopy, the patient is positioned in a prone position on a standard examination table with the foot extending beyond the edge of table with support under the distal part of the leg. With the ankle in neutral position, relevant surface ankle anatomy is marked on skin, including the sole of the foot, medial – and lateral malleolus and the lateral and medial border of the Achilles tendon. A straight line, perpendicular to the sole of the foot, is drawn from the inferior pole of the lateral malleolus to the medial side. The planned posterolateral and posteromedial portals are located along this line, 5 mm anterior to the lateral and medial border of the Achilles tendon (Figure 3).

reacae.32284.fs2509022en-figure3.png

Figure 3. A: left ankle, seen from an posterior perspective. Number 1 refers to the anterolateral portal, and number 2 refers to the anteromedial portal; B: left ankle, seen from an lateral perspective. Number 1 refers to the anterolateral portal. With the foot in neutral position (90 °), a straight line (blue), parallel to the sole of the foot, is drawn from the inferior pole of the lateral malleolus to the medial side. The planned posterolateral and posteromedial portals are located along this line, 5 mm anterior to the lateral and medial border of the Achilles tendon (ML, lateral malleolus; MM medial malleolus; AT, Achilles tendon).

These posteromedial and lateral hindfoot portals, introduced in 2000 by van Dijk et al.(25), are anatomically proven to be safe and reliable and typically provide excellent access to the posterior aspects of the ankle and subtalar joints, including the extra-articular hindfoot structures(26). All subsequent steps are identical to those described of the anterior ankle arthroscopy.

Portal placement and arthroscope introduction

Anterior Ankle Arthroscop(23)

Proper portal placement is essential for optimal visualization of the anterior ankle. The anteromedial portal is created first, serving primarily as the visual portal. A 2-mm stab incision is made at the pre-marked site using an 11-blade. Through this incision, a 2.4 mm sheath loaded with an obturator is inserted intra-articularly with the ankle in maximum dorsiflexion to prevent cartilage damage. The obturator is then removed, allowing the needle arthroscope to be introduced through the sheath. Joint distention is achieved by connecting sterile saline to the sheath, using a syringe, a pressure IV infuser bag, or an arthroscopic pump.

The anterolateral portal is created under direct intra-articular visualization, primarily serving as the intervention portal for introducing various instruments, as above-mentioned. The correct positioning can first be determined using a needle, which is inserted to verify the intended location. Once confirmed, the portal is established using the same technique described for the anteromedial portal.

Posterior ankle arthroscopy(24)

Comparable steps can be followed for posterior ankle arthroscopy, although this approach presents specific technical challenges(26). The posterolateral portal is created first, following the same steps as described previously. Before inserting the blunt trocar in the direction of the first web space, blunt dissection is performed using a mosquito clamp, with careful attention to avoid injury to the sural nerve.

The posteromedial portal is then created under direct visualization, using the same technique as for the posterolateral portal. To achieve adequate visualization of the posterior ankle structures, a 2-mm shaver is used to carefully debride the fatty tissue until the posterior structure are visualized.

Closure

After completing the needle arthroscopy, the joint is aspirated to remove fluid, and all instruments are withdrawn. Due to minimal soft tissue damage, closure with sutures is unnecessary. Instead, sterile wound closure strip or a simple bandage can be applied. Depending on the type of procedure performed, a pressure bandage or cast may be applied if required.

Indications: surgical applications

Ankle Impingement

Ankle impingement is mechanical pain resulting from osseous or soft tissue abnormalities, which can occur in both the anterior and posterior regions of the ankle(27). Although patients may achieve symptomatic relief through conservative therapy, certain cases require surgical resection(28,29,30). This typically consists of osteophyte removal or excision of any impinging soft tissue, traditionally performed through standard anterior or posterior ankle arthroscopy conducted in the operating room. The availability of a range of tailored, small-surgical instruments now enables these procedures to be performed using needle arthroscopy.

Colasanti et al.(15) demonstrated the clinical feasibility of using needle arthroscopy to treat anterior ankle impingement under local anesthesia. In their prospective cohort of 31 patients, standard anteromedial and anterolateral portals were used to resect soft tissue or osseous impingement. After a minimum follow-up of 12 months, patients reported significant improvements across all Foot and Ankle Outcome Score (FAOS) domains, including pain, symptoms, quality of life, sports participation, and daily activities. Notably, nearly all patients (96%) returned to sports within four weeks, and all employed patients resumed work. Lastly, the overall experience was reported as positive, with 94% of patients indicating they would be willing to undergo the procedure again.

Similarly, Mercer et al.(16) evaluated the role of needle arthroscopy for posterior ankle impingement in a retrospective series of 10 patients, performed under local anesthesia. After a mean follow-up of 13.3 months, they demonstrated similar improvements across all domains of the FAOS questionnaire. All patients who participated in sports preoperatively returned to sport within a median of 4.1 weeks, and the median time to return to work was 3.4 days. Furthermore, 100% expressed willingness to undergo the same procedure again.

Delivery of injectable agents

Intra-articular injections play an important role in the management of foot and ankle pathology. Accurate delivery is essential to ensure optimal therapeutic effect. Currently, intra-articular injections into the tibiotalar joint are often performed using palpation, with reported ‘low’ accuracy rates ranging from 67% to 77%(31). The added value of ultrasound guidance appears limited, as it does not consistently improve injection accuracy(32).

In this context, Stornebrink et al.(14) investigated the potential of bedside needle arthroscopy as a delivery system for hyaluronic acid in the tibiotalar joint under local anaesthesia. Their findings suggest an improvement in accuracy, with successful intra-articular delivery achieved in 88% of cases (21 out of 24 patients), and 100% accuracy rate in those without anterior joint obliteration. Additionally, the procedure was well tolerated, with no complications reported during a two-week follow-up period. Tolerability was further supported by the fact that all patients (100%) indicated they would be willing to undergo the procedure again.

Syndesmotic injuries

Unstable syndesmotic injuries are frequently associated with concomitant intra-articular damage, particularly cartilage lesions of the ankle joint(33). In a recent prospective case series, Walinga et al. showed that fifteen of the sixteen elite athletes (94%) undergoing suture-button fixation demonstrated concomitant cartilage lesions, as observed through needle arthroscopy. The majority of these lesions were graded as minor (i.e. superficial cartilage damage) and were predominantly localized to the talar dome(34,35). Early identification and individualized preventive interventions may play a critical role in preventing further cartilage damage during the initial, subclinical phase of the degenerative cascade(36). Furthermore, adding a needle arthroscopic assessment can (dis)confirm the diagnosis of an unstable acute or chronic syndesmotic injury in a dynamic matter(37).

Undiagnosed foot and ankle symptomatology

Needle arthroscopy may offer significant diagnostic advantages in cases of persistent ankle symptoms where standard imaging modalities, including Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), fail to detect underlying pathology(9,17,38,39). Dankert et al.(19) presented a case involving a patient with chronic anteromedial ankle pain and mechanical symptoms, in whom repeated MRI scans did not reveal a causative lesion. In-office needle arthroscopy subsequently identified and allowed for the removal of a chronic osseous loose body resulting in significant symptomatic relief(19).

Tendon pathology

Tendoscopy has gained increasing attention in recent years as a minimally invasive technique for diagnosing and treating tendon pathologies, including disorders of the peroneal tendons, tibialis posterior tendon, and Achilles tendon(40,41,42). Compared to open surgery, tendoscopy offers lower complication rates, faster recovery, and improved visualization, with added diagnostic value over imaging modalities such as MRI(43,44). However, the limitations associated with conventional tendoscopy using rod-lens arthroscopes reduce its practicality, especially for purely diagnostic purposes or in outpatient settings.

The use of needle arthroscopy may help overcome these limitations. Several cadaveric studies have demonstrated that this system provides excellent visualization and safe operative access to key tendon structures—including the tibialis posterior, peroneal, and Achilles tendons—without causing iatrogenic damage(45,46). However, no clinical studies have been conducted to date.

Risks/Complications

As with any emerging technique, safety remains an important consideration. While conventional arthroscopy is generally safe, complications, though uncommon (1.5–11%) do occur, with neurological injuries reported most frequently(47). Although needle arthroscopy is smaller and less invasive, differences in setting (e.g., outpatient procedures), instrumentation handling, and visual feedback may influence both the incidence and type of complications, making direct comparisons with conventional arthroscopy challenging.

A recent systematic review (n = 1624 patients) showed only minor complications after the use of needle arthroscopy(48). This review highlights needle arthroscopy as a low-risk procedure, with reported complication rates between 0% and 9.68%, all classified as minor (grade I). The most common adverse event was vasovagal response, occurring in up to 8.33% of cases. These findings reinforce the favourable safety profile of needle arthroscopy.

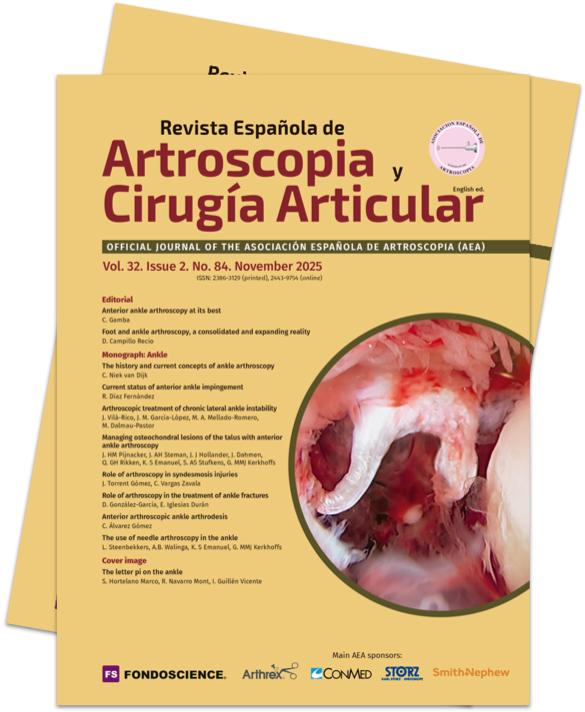

General pearls and pitfalls of needle arthroscopy

When considering needle arthroscopy for patients with ankle pathology, it is important to consider the potential pearls and pitfalls in advance. An overview of these considerations can be found in Table 1.

Conclusion

This article provides an overview of needle arthroscopy’s role in intra-articular anterior and posterior ankle joint pathology, including historical background, surgical technique, clinical indication, complications and the pearls & pitfalls. It can be used for the treatment of ankle impingement under local anesthesia, as well as in a supportive role to confirm syndesmotic instability and concurrently treat potential intra-articular pathologies. In addition, it may improve the accuracy of intra-articular delivery of injectable agents. Needle arthroscopy may also offer diagnostic value in cases of persistent ankle symptoms where conventional imaging fails to detect the underlying pathology. As with any emerging technique, safety remains a key concern. Nevertheless, needle arthroscopy is considered a low-risk procedure.

However, despite promising from cadaveric and clinical studies, the current body of literature remains limited. Important questions remain unanswered—such as the true cost-effectiveness and efficacy of the needle arthroscope and its long-term clinical outcomes. Yet, further research is needed to fully establish its role and to determine whether its early advantages can be consistently reproduced across broader clinical settings and among varying levels of surgical expertise.

Figuras

Figure 1. The needle-like arthroscopic system consists of a (chargeable) tablet control unit (A) a 2-mm diameter, disposable arthroscope (B).

Figure 2. A: right ankle, seen from an anterolateral perspective. Number 2 refers to the anterolateral portal; B: right ankle, seen from an anterior perspective. Number 1 refers to the anteromedial portal, and number 2 refers to the anterolateral portal. (ML, lateral malleolus; MM medial malleolus; N, superficial peroneal nerve; TibA, tibialis anterior muscle tendon).

Figure 3. A: left ankle, seen from an posterior perspective. Number 1 refers to the anterolateral portal, and number 2 refers to the anteromedial portal; B: left ankle, seen from an lateral perspective. Number 1 refers to the anterolateral portal. With the foot in neutral position (90 °), a straight line (blue), parallel to the sole of the foot, is drawn from the inferior pole of the lateral malleolus to the medial side. The planned posterolateral and posteromedial portals are located along this line, 5 mm anterior to the lateral and medial border of the Achilles tendon (ML, lateral malleolus; MM medial malleolus; AT, Achilles tendon).

Tablas

Información del artículo

Cita bibliográfica

Autores

Lars Steenbekkers

Departamento de Cirugía Ortopédica y Medicina Deportiva. Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC). Sede AMC. Universidad de Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Ciencias del Movimiento de Ámsterdam. Programas de Deporte y Salud Musculoesquelética. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Centro Académico de Medicina Deportiva Basada en la Evidencia (ACES). Amsterdam UMC. Países Bajos

Colaboración de Ámsterdam para la Salud y la Seguridad en el Deporte (ACHSS). Centro de Investigación del Comité Olímpico Internacional (COI). Amsterdam UMC. Países Bajos

Alex B Walinga

Departamento de Cirugía Ortopédica y Medicina Deportiva. Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC). Sede AMC. Universidad de Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Ciencias del Movimiento de Ámsterdam. Programas de Deporte y Salud Musculoesquelética. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Centro Académico de Medicina Deportiva Basada en la Evidencia (ACES). Amsterdam UMC. Países Bajos

Colaboración de Ámsterdam para la Salud y la Seguridad en el Deporte (ACHSS). Centro de Investigación del Comité Olímpico Internacional (COI). Amsterdam UMC. Países Bajos

Kaj S Emanuel

Departamento de Cirugía Ortopédica y Medicina Deportiva. Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC). Sede AMC. Universidad de Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Ciencias del Movimiento de Ámsterdam. Programas de Deporte y Salud Musculoesquelética. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Centro Académico de Medicina Deportiva Basada en la Evidencia (ACES). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Colaboración de Ámsterdam para la Salud y la Seguridad en el Deporte (ACHSS). Centro de Investigación del Comité Olímpico Internacional (COI). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Gino MMJ Kerkhoffs

Departamento de Cirugía Ortopédica y Medicina Deportiva. Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC). Sede AMC. Universidad de Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Ciencias del Movimiento de Ámsterdam. Programas de Deporte y Salud Musculoesquelética. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Centro Académico de Medicina Deportiva Basada en la Evidencia (ACES). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Colaboración de Ámsterdam para la Salud y la Seguridad en el Deporte (ACHSS). Centro de Investigación del Comité Olímpico Internacional (COI). Amsterdam UMC. Ámsterdam. Países Bajos

Ethical responsibilities

Conflicts of interest. The author Prof. dr. Gino Kerkhoffs declare the following conflicts of interest: Consultant of Arthrex.

Financial support. This study has received no financial support.

Protection of people and animals. The authors declare that this research has not involved human or animal experimentation.

Data confidentiality. The authors declare that the protocols of their work centre referred to the publication of patient information have been followed.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Disclosures

The Department of Orthopedic Surgery and Sports Medicine of the Amsterdam UMC received an unrestricted research grant from Arthrex. Prof. dr. Gino Kerkhoffs is a consultant for Arthrex.

Referencias bibliográficas

-

1Van Dijk CN, van Bergen CJ. Advancements in ankle arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(11):635-46.

-

2Vega J, Dalmau-Pastor M, Malagelada F, et al. Ankle Arthroscopy: An Update. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(16):1395-407.

-

3Vega J, Karlsson J, Kerkhoffs G, Dalmau-Pastor M. Ankle arthroscopy: the wave that's coming. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(1):5-7.

-

4Halbrecht JL, Jackson DW. Office arthroscopy: a diagnostic alternative. Arthroscopy. 1992;8(3):320-6.

-

5Meister K, Harris NL, Indelicato PA, Miller G. Comparison of an optical catheter office arthroscope with a standard rigid rod-lens arthroscope in the evaluation of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24(6):819-23.

-

6Patton GW, Zelichowski JE. Office-based ankle arthroscopy. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1994;11(3):513-22.

-

7Small N, Del Gallo W. Chapter: Office Foot and Ankle Arthroscopy. En: Guhl James F, Boynton Melbourne D, Parisien Serge J (eds.). Foot and ankle arthroscopy. New York: Springer; 2004. pp. 257-63.

-

8McMillan S, Schwartz M, Jennings B, et al. In-Office Diagnostic Needle Arthroscopy: Understanding the Potential Value for the US Healthcare System. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2017;46(5):252-6.

-

9Zhang K, Crum RJ, Samuelsson K, et al. In-Office Needle Arthroscopy: A Systematic Review of Indications and Clinical Utility. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(9):2709-21.

-

10Stornebrink T, Stufkens SAS, Appelt D, et al. 2-Mm Diameter Operative Tendoscopy of the Tibialis Posterior, Peroneal, and Achilles Tendons: A Cadaveric Study. Foot Ankle Int. 2020;41(4):473-8.

-

11DiBartola AC, Rogers A, Kurzweil P, et al. In-Office Needle Arthroscopy Can Evaluate Meniscus Tear Repair Healing as an Alternative to Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2021;3(6):e1755-e60.

-

12Gauci MO, Monin B, Rudel A, et al. In-Office Biceps Tenotomy with Needle Arthroscopy: A Feasibility Study. Arthrosc Tech. 2021;10(5):e1263-e8.

-

13Kaplan DJ, Chen JS, Colasanti CA, et al. Needle Arthroscopy Cheilectomy for Hallux Rigidus in the Office Setting. Arthrosc Tech. 2022;11(3):e385-e90.

-

14Stornebrink T, Stufkens SAS, Mercer NP, et al. Can bedside needle arthroscopy of the ankle be an accurate option for intra-articular delivery of injectable agents? World J Orthop. 2022;13(1):78-86.

-

15Colasanti CA, Mercer NP, García JV, et al. In-Office Needle Arthroscopy for the Treatment of Anterior Ankle Impingement Yields High Patient Satisfaction With High Rates of Return to Work and Sport. Arthroscopy. 2022;38(4):1302-11.

-

16Mercer NP, Samsonov AP, Dankert JF, et al. Improved Clinical Outcomes and Patient Satisfaction of In-Office Needle Arthroscopy for the Treatment of Posterior Ankle Impingement. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2022;4(2):e629-e38.

-

17Gill TJ, Safran M, Mandelbaum B, et al. A Prospective, Blinded, Multicenter Clinical Trial to Compare the Efficacy, Accuracy, and Safety of In-Office Diagnostic Arthroscopy With Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Surgical Diagnostic Arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(8):2429-35.

-

18Stornebrink T, Janssen SJ, Kievit AJ, et al. Bacterial arthritis of native joints can be successfully managed with needle arthroscopy. J Exp Orthop. 2021;8(1):67.

-

19Dankert JF, Shimozono Y, Williamson ERC, Kennedy JG. Application of nano arthroscopy in the office setting for the removal of an intra-articular loose osseous body not identified by magnetic resonance imaging: A case report. Foot Ankle Surg. 2021;1(1):100012.

-

20Stornebrink T, Altink JN, Appelt D, et al. Two-millimetre diameter operative arthroscopy of the ankle is safe and effective. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(10):3080-6.

-

21Inoue J, Yasui Y, Sasahara J, et al. Comparison of Visibility and Risk of Neurovascular Tissue Injury Between Portals in Needle Arthroscopy of the Anterior Ankle Joint: A Cadaveric Study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2023;11(6):23259671231174477.

-

22Takao M, Uchio Y, Shu N, Ochi M. Anatomic bases of ankle arthroscopy: study of superficial and deep peroneal nerves around anterolateral and anterocentral approach. Surg Radiol Anat. 1998;20(5):317-20.

-

23Stornebrink T, Walinga AB, Stufkens SAS, Kerkhoffs G. Wide-Awake Needle Arthroscopy of the Anterior Ankle: A Standardized Approach. Arthrosc Tech. 2024;13(4):102901.

-

24Chen JS, Kaplan DJ, Colasanti CA, et al. Posterior Hindfoot Needle Endoscopy in the Office Setting. Arthrosc Tech. 2022;11(3):e273-e8.

-

25Van Dijk CN, Scholten PE, Krips R. A 2-portal endoscopic approach for diagnosis and treatment of posterior ankle pathology. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(8):871-6.

-

26Van Dijk CN, Vuurberg G, Batista J, d'Hooghe P. Posterior ankle arthroscopy: current state of the art. J ISAKOS. 2017;2(5):269-77.

-

27Tol JL, van Dijk CN. Anterior ankle impingement. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11(2):297-310, vi.

-

28Tol JL, Verheyen CP, van Dijk CN. Arthroscopic treatment of anterior impingement in the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(1):9-13.

-

29Zwiers R, Wiegerinck JI, Murawski CD, et al. Surgical treatment for posterior ankle impingement. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(7):1263-70.

-

30Zwiers R, Wiegerinck JI, Murawski CD, et al. Arthroscopic Treatment for Anterior Ankle Impingement: A Systematic Review of the Current Literature. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(8):1585-96.

-

31Hall MM. The accuracy and efficacy of palpation versus image-guided peripheral injections in sports medicine. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2013;12(5):296-303.

-

32Gilliland CA, Salazar LD, Borchers JR. Ultrasound versus anatomic guidance for intra-articular and periarticular injection: a systematic review. Phys Sportsmed. 2011;39(3):121-31.

-

33Rellensmann K, Behzadi C, Usseglio J, et al. Acute, isolated and unstable syndesmotic injuries are frequently associated with intra-articular pathologies. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29(5):1516-22.

-

34Walinga AB, Dahmen J, Stornebrink T, et al. Fifteen out of 16 elite athletes showed concomitant low-grade cartilage lesions of the ankle with unstable syndesmotic injuries: concerns from a prospective case series. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2024;10(1):e001879.

-

35Walinga AB, Dahmen J, Stornebrink T, Kerkhoffs G. Needle Arthroscopic Inspection and Treatment of (Osteo)chondral Lesions of the Ankle in Unstable Syndesmotic Injuries Treated With Suture Button Fixation: A Standardized Approach. Arthrosc Tech. 2023;12(7):e1121-e6.

-

36Dahmen J, Karlsson J, Stufkens SAS, Kerkhoffs G. The ankle cartilage cascade: incremental cartilage damage in the ankle joint. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29(11):3503-7.

-

37Lubberts B, Massri-Pugin J, Guss D, et al. Arthroscopic Assessment of Syndesmotic Instability in the Sagittal Plane in a Cadaveric Model. Foot Ankle Int. 2020;41(2):237-43.

-

38Amin N, McIntyre L, Carter T, et al. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Needle Arthroscopy Versus Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Meniscal Tears of the Knee. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(2):554-62.e13.

-

39DiBartola AC, Rogers A, Kurzweil P, et al. In-Office Needle Arthroscopy Can Evaluate Meniscus Tear Repair Healing as an Alternative to Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2021;3(6):e1755-e60.

-

40Kennedy JG, van Dijk PA, Murawski CD, et al. Functional outcomes after peroneal tendoscopy in the treatment of peroneal tendon disorders. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(4):1148-54.

-

41Cychosz CC, Phisitkul P, Barg A, et al. Foot and ankle tendoscopy: evidence-based recommendations. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(6):755-65.

-

42Bulstra GH, Olsthoorn PG, Niek van Dijk C. Tendoscopy of the posterior tibial tendon. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11(2):421-7, viii.

-

43Vega J, Batista JP, Golanó P, et al. Tendoscopic groove deepening for chronic subluxation of the peroneal tendons. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34(6):832-40.

-

44Vega J, Cabestany JM, Golanó P, Pérez-Carro L. Endoscopic treatment for chronic Achilles tendinopathy. Foot Ankle Surg. 2008;14(4):204-10.

-

45Kanakamedala A, Chen JS, Kaplan DJ, et al. In-Office Needle Tendoscopy of the Peroneal Tendons. Arthrosc Tech. 2022;11(3):e365-e71.

-

46Dankert JF, Mercer NP, Kaplan DJ, et al. In-Office Needle Tendoscopy of the Tibialis Posterior Tendon with Concomitant Intervention. Arthrosc Tech. 2022;11(3):e339-e45.

-

47Yammine K, Assi C. Neurovascular and tendon injuries due to ankle arthroscopy portals: a meta-analysis of interventional cadaveric studies. Surg Radiol Anat. 2018;40(5):489-97.

-

48Walinga AB, van der Stappen T, Kerkhoffs GMMJ, Emanuel KS. Only Minor Complications are Reported After Needle Arthroscopy: A Systematic Review. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehab. 2025:101158.

Descargar artículo:

Licencia:

Este contenido es de acceso abierto (Open-Access) y se ha distribuido bajo los términos de la licencia Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND (Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional) que permite usar, distribuir y reproducir en cualquier medio siempre que se citen a los autores y no se utilice para fines comerciales ni para hacer obras derivadas.

Comparte este contenido

En esta edición

- Anterior ankle arthroscopy at its best

- Foot and ankle arthroscopy, a consolidated and expanding reality

- The history and current concepts of ankle arthroscopy

- Current status of anterior ankle impingement

- Arthroscopic treatment of chronic lateral ankle instability

- Managing osteochondral lesions of the talus with anterior ankle arthroscopy

- Role of arthroscopy in syndesmosis injuries

- Role of arthroscopy in the treatment of ankle fractures

- Anterior arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis

- The use of needle arthroscopy in the ankle

- The letter pi on the ankle

Más en PUBMED

Más en Google Scholar

Revista Española de Artroscopia y Cirugía Articular está distribuida bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional.